By Geoff Gehman ’80

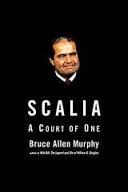

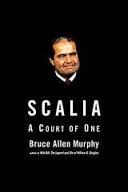

The biography of Antonin Scalia by Bruce Murphy is a forensic study of the Supreme Court’s most extreme justice. In A Court of One (Simon & Schuster), the Fred Morgan Kirby Professor of Civil Rights creates a 3-D map of the constitution of a strict Constitutionalist, or Originalist, who opposes passing a federal amendment for same-sex marriage largely because same-sex marriage is not mentioned in the Constitution.

Bruce Murphy

Murphy meticulously portrays Scalia with almost as many personalities as there are members of the court. There’s the master debater who pulverizes lawyers’ arguments. The brilliant bully who harangues colleagues in long footnotes to his dissents. The ardent Catholic who, in speeches and interviews, scoffs at those who scoff at his belief in miracles and the Devil. “The Ninopath,” who has alienated liberals, conservatives, and centrists alike, sabotaged his quest to become chief justice, and turned the most powerful bench in the land into his own personal island.

Scalia is a fascinating, fathomless subject for Murphy, the author of books about four other Supreme Court justices, including Abe Fortas and William O. Douglas, both of whom rivaled Scalia in the court of public controversy.

Q: You open A Court of One with Scalia at Barack Obama’s second presidential inauguration, wearing a black-velvet hat with peaked corners, a replica of one worn by his hero, the martyred lawyer Thomas More. The unusual headwear ignited a wildfire of debate about Scalia’s motivations. What’s your take?

A: We will never know for sure what his motivation was. I think it’s quite possible that he wore the hat because it was cold and because he thought it was warmer than his other possibility, which would have been a kind of silk skullcap. Or it could have been that by staying warm he could make a statement about the Obama administration. Maybe he was saying, “I’m stuck four more years with a Democrat in the White House, so I feel like a martyr.”

The hat is a wonderful example of how Scalia tries to brand himself as a person who stands apart. It allows him to do things in public that can be reinterpreted by other people, and since it’s their interpretation he can stand apart and say, “That wasn’t what I was intending to say. I wasn’t intending to protest against the Obama administration’s health-care law.”

Q: What do you admire most about Scalia? I admire his erudite defense of the Sixth Amendment right for defendants to confront an accuser in open court, when he cited everyone from a Roman emperor to Shakespeare’s Richard II.

A: I admire his ability to argue. He can duel with lawyers arguing before the court and best them continually by seeing the central part of their arguments—“the jugular”—and then blowing their arguments apart. I admire his intellect. This is what you want in Supreme Court justices. You want the smartest people you can find. You want people who can take legal puzzles, break them apart, figure out the answer, and then explain the solution in language that people can understand.

Scalia: A Court of One

Scalia does all of this brilliantly, often in intriguing, novel ways. You’ll see him use historical references, cultural references, metaphors, analogies almost never used in judicial opinions. He’ll reference phrases that you’ve never heard of, like “legalistic argle-bargle.” When you look that up, etymologically, the term is “argy-bargy”—a rhyming reduplication of “mumbo-jumbo.” It acquires a meaning through culture, and in this case it means you can’t trust this argument because it’s back and forth, like a tennis match.

Q: Shall we give Scalia a badge of merit for volleying “legalistic argle-bargle” on the Supreme Court’s court?

A: Absolutely. It’s the phrase most people want to talk about. They may not be able to name two judges on the court, but they can usually remember “legalistic argle-bargle.” I think that’s a real accomplishment. It’s a style that people like to see, to read. And Scalia has made that contribution to the literature of the court.

Q: What do you admire least about Scalia? He can be crude and rude, as when he delivered an Italian curse to a reporter and photographer who asked him about attending a special mass for legal professionals.

A: I question his inability to try to get along with other members of the court and fulfill his role as a justice for the entire United States. With all of his knowledge and expertise he locks into this one solution and doesn’t consider other ways of approaching conflicts. At times he’s been so angry with his colleagues’ decisions that he’s issued a revision of his dissent and added numerous footnotes criticizing portions of the opinion and criticizing other justices personally. He couldn’t stop until he had bludgeoned their arguments into a puddle.

In criticizing his colleagues so harshly and so repeatedly the price he paid is that he gave up any possibility of uniting the conservatives into a group of five and leading the court. He also drove the centrist judges away from him so that from time to time they would vote with the liberals or with the conservatives. From 1996 to 2005 the conservatives couldn’t bring about a majority. It’s almost like Scalia was out on his own island.

Q: What do you think of his Originalism theory? I can understand that he can’t allow for the “brutality” of partial-birth abortion because the Constitution advocates justice and domestic tranquility. And yet I can agree with UCLA law professor Adam Winkler’s criticism that “Scalia is an originalist: he has his own original view of the Constitution, ungrounded in history and steeped in conservative politics.”

A: Scalia’s explanation of his interpretation of Originalism is: We’re going to simply look at the meaning of the words of the Constitution or the amendments in the lives of the people at the time that the words were ratified. For this meaning he will look at old histories, old dictionaries, whatever he can find to give him a sense of where he wants to go. He’s essentially saying, “I need to take you in my Antonin Scalia time machine so that you will have no doubt as to what the meaning was at the time of the ratification. I can interpret which facts are true, and which facts are not true.”

He doesn’t always go where he wants to go. He upholds flag-burning because it has to be protected in the Second Amendment. He actually is excellent at protecting the rights of defendants in search-and-seizure cases that involve technology: thermal-image cameras, DNA searches of prisoners. But his argument is always going to be: If I don’t see the word “contraception,” the word “abortion,” the phrase “right to die with dignity” in the first 10 amendments, I’m not going to give you that right because I’m going to tell you the framers never intended you to have the right.

Scalia has done a marvelous job of branding himself as the leader of the theory of our time. Yet you see a number of times that he doesn’t use his Originalism when it doesn’t get him where he wants to go. He ignores it, or he reads the Founding Era history in a different way. What he is actually doing is using a grab-bag of history, just reaching in and picking a definition here, a piece of historical evidence there. No major Founding Era historian agrees with him that this is a process they would use in academia. They all know that analyzing history of any kind is very tricky work, that it’s as much art form as scholarly detection. They say you can’t do this and even if you could, it’s no way to judge cases.

Q: You had three years of undergraduate aid thanks to a “Community of Scholars” grant from the Mellon Foundation. How did the Mellon students help you dig deeper into Scalia’s character?

A: We spent two years on the chapter on Scalia’s term on the [U.S.] Court of Appeals [for the District of Columbia], before he was appointed, confirmed, and placed on the Supreme Court. I asked the Mellon students—there were three each summer, six total—to look through all of his 60 opinions for the appeals court. And they said, “We can’t find Originalism here. In fact, we can’t really find what his view is. We can’t recognize him.”

So we went back through all these cases again. And there were several different theories Scalia was using. Later, I was doing some research on my own, trying to find the beginning of his Originalist theory, when I discovered in an obscure government publication a funny luncheon speech that he made for a conference organized by the attorney general where he suggests something called “original meaning.” It’s the sort of paradigm shift you find in academia. Does he define it? No. Do we know what it means? No. Do we know how you find it? No.

I thought, “Why is he doing that?” And then I checked the date: It was the weekend before he was going to meet with [President Ronald] Reagan about an appointment to the Supreme Court. And I thought, “Aha—he’s offered all these theories as an appeals court judge, but, apparently, if he gets to the Supreme Court, he’s going to be doing something else. He’s come up with ‘original meaning’ because he’s essentially lobbying for the position.”

The speech pretty much confirmed what the students and I had discovered and discussed in the previous summers. So that gets me off and running on this whole parallel storyline for the book, which is: How does Scalia’s Originalism develop over time? The storyline that we were able to develop becomes much more nuanced and much more accurate. You understood how Scalia was evolving.

Q: Can you put your finger on one key way that the Mellon students helped change your process and analysis?

A: I had a game with one of my Mellon students: How many speeches can you find that Scalia made off the court? At the end of two months I came in with a very substantial pile of material. I was proud that in middle age I had mastered the technology. And my student—Lori Weaver [’06]; she went on to law school at Penn—came in and she had well over two and a half to three times the material I had found. She had speeches I did not know Scalia had given, transcripts of speeches I could not find. I said, “How did you do this?” She said, “I just kept up the search. In the end I just hit more Google searches than you hit.”

That was fairly early in my research, and that was very good advice. So I set up a series of Google alerts. One of the side benefits of technology is that nothing disappears, which means that pretty much nothing that Scalia did off the court was hidden. I ended up getting an email notice from a right-to-life newsletter with a link to a speech he had given in [Fribourg, Switzerland]. It wasn’t there long; it was gone within a couple of weeks. It helped me establish a pattern about Scalia’s behavior off the court. He would do something outrageous on the court, he would lose a vote, he would be angry, he would erupt like a volcano off the court, and his colleagues would react to his reaction. There were two parallel tracks to his life and you could understand him better by knowing how the tracks worked.

I didn’t realize it at first but I had actually enrolled in a tutorial in which the student was going to teach me about technology.

Q: What will be Scalia’s most valuable legacy on the court? He certainly removed justices from their robes, exposed them as human beings with biases and faults, reminded everyone that the court flexes along with the Constitution.

A: I think people will pick up Originalism as a tool. It will not dictate decisions; it’s going to be a way that judges can frame opinions and decide cases. We might see down the road a privacy amendment, something that will safeguard Americans against various forms of technological intervention. If we do, you will almost certainly hear the words of Antonin Scalia. He is very good about arguing that the framers intended for the government, and for devices of all kinds—including electronic ones—staying out of our personal lives.

There’s a law professor named Jonathan Turley at George Washington who says that Scalia is the first celebrity justice. I don’t think he is; I think William O. Douglas was. But Scalia is certainly the first celebrity justice in the 24/7/cable news/internet period. When Scalia acts out, when he creates controversy, he makes it acceptable for political figures or members of the press to treat him just like any other politician.

The major change that Scalia has wrought, and maybe not necessarily for the better, is that he has made the court vulnerable. He’s made people understand that this is just another political body, and with that comes the realization that it can be attacked with political means. He has also changed the way that Supreme Court justices do their job. Because of him, Ruth Bader Ginsburg has been giving speeches everywhere. Sonia Sotomayor is present at the dropping of the New Year’s ball in Times Square with her family. And Clarence Thomas becomes the grand marshal for the Daytona 500 race.

Q: A Court of One has been reviewed all over the map, from The New York Times to The New Republic. Can you point to a memorable, indelible reaction?

A: When I got back to school after the summer there were messages that had been there for weeks and weeks. One was from a friend of Scalia’s I didn’t even know existed. He left two emails and the first one said, “I know Scalia well. I traveled with him around the world. I just wanted you to know that you got him exactly right. That’s the guy I know.” And then he left another email to give him a call. When I called him he said the book brought back a lot of memories. He’s a retired Washington bureaucrat who knew Scalia when he was back in the Nixon administration.

I asked him, “Well, have you gotten any reaction from Scalia?” Because that’s really what people ask me. I’ve heard nothing: Scalia was unusually quiet this summer; he’s given very few speeches, if any. And this fellow said he had asked Scalia, “Well, what do you think of this book?” And Scalia told him, “I don’t want to talk about that.” And so I thought, “Well, okay, at least he’s aware of it.”