Will Congress revive the ACIR it killed in 1996 after Prof. John Kincaid departed as director?

By Stephen Wilson

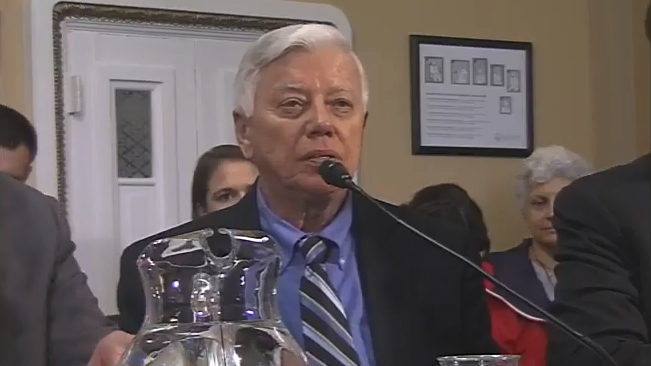

Prof. John Kincaid testified in Washington, D.C., last month before the U.S. House of Representatives’ bipartisan Speaker’s Task Force on Intergovernmental Affairs. He supported revival of a commission he once led: the United States Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (ACIR). Some House members want to reactivate it. Kincaid is hopeful but doubts it will gain traction despite the obvious need.

Wonder why the ACIR matters? If the recent tax bill, recreational marijuana, sanctuary cities, Obamacare, or sports betting are policies that affect you, then learn from this interview with Kincaid, professor of government and law and director of the Robert B. and Helen S. Meyner Center for the Study of State & Local Government, why the ACIR matters more than people realize.

What is the ACIR origin story?

The ACIR was formed in 1959. It was an era of desegregation, which created conflict between states and the federal government. The conflict had been building because states felt a substantial loss of power that began during the New Deal and continued with the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision in 1954. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, vowing to restore some power to the states, convinced Congress to establish a temporary bipartisan Commission on Intergovernmental Relations in 1953. One of its recommendations was for Congress to create a permanent advisory commission, which it did in 1959.

What was the ACIR structure?

The bipartisan commission consisted of three private citizens, three Cabinet-level executive officers, four governors, three state legislators, four mayors, and three county officers appointed by the president. Also, the U.S. House and Senate appointed three members each. I was appointed executive director by a majority vote of the commission and was responsible for hiring all other staff and overseeing all research and administrative functions.

Was it effective?

Fairly effective and highly respected. As an advisory body, it could be hard to make Congress pay attention. However, a number of recommendations were adopted by Congress, some were promulgated by the White House, and others were adopted by state and local governments. An ACIR recommendation some people might recognize is the Intergovernmental Personnel Act, which allows federal employees to work temporarily in counterpart state, tribal, or local agencies, and vice versa. For example, a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency employee could be detailed temporarily to the PA DEP.

The ACIR was a prime mover of General Revenue Sharing (1972-1986), which distributed few-strings-attached federal funds to state, local, and tribal governments. The ACIR also issued many information reports that were widely used by public officials, scholars, and students. Lafayette’s Kirby Library has a nearly complete collection of ACIR’s reports.

What happened in 1996 when it was defunded?

Two things occurred. Republicans gained control of both houses of Congress in the 1994 elections and promised to trim the federal bureaucracy. So, the ACIR became a target to defund even though it had only 18 employees and a tiny budget by 1996. Still, Republicans could say they eliminated a federal agency. The other factor in defunding was that the ACIR fell out of favor with the Clinton administration. Tasked by Congress in 1995 with identifying federal mandates to eliminate or amend, the ACIR inadvertently triggered a political firestorm. Its draft recommendations displeased many Clinton Democrats. So, even though Clinton met with the ACIR in 1993 to express support, his White House did not vigorously defend the ACIR against Congress’s budget-cutters.

You were gone by that time?

Yes, I started there in December 1986 as director of research and became executive director in early 1988. I left voluntarily in 1994 to return to academic life. During my time, the ACIR brought many issues of federalism to the attention of federal, state, and local officials, as well as citizens, encouraged states to litigate more on states’ needs before the Supreme Court, and helped design and then support passage of the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act (1995), which continues to shield state and local taxpayers from Congress’s penchant for enacting laws that state and local governments must pay for. Near the end, though, I spent more and more time defending the ACIR budget in Congress.

Why do leaders want to bring it back?

I am not entirely sure. None of House members addressed it specifically at the hearing. They recognize, though, that our federal system has become dysfunctional, and many issues need to be dealt with in the intergovernmental system. Consider the recent tax bill, the varied state approaches to marijuana (which remains illegal under federal law), the debate over sanctuary cities, climate change, the recent Supreme Court ruling on sports betting, and states’ varied policies on health-insurance marketplaces and Medicaid expansion under Obamacare. A revived bipartisan ACIR could, with enough congressional support, help find ways to resolve a myriad of federal-state-tribal-local issues.

What suggestions did you offer during your testimony?

Bipartisanship. The former ACIR was created in era of bipartisanship and worked best during that era, but partisan polarization began rising during the 1970s and has hit an unprecedented high point today. Overall, what really killed the bipartisan ACIR was polarization. A new ACIR would have to chart a treacherous course between the Scylla of polarization and Charybdis of irrelevance.

I supported the addition of two tribal members to a new ACIR, suggested the addition of at least one township officer, and made several other suggestions about membership and the quorum rule so as to mitigate polarization on a new ACIR.

A new ACIR needs a more specific, pragmatic, and practical focus. The former ACIR was too broad. A new ACIR could be modeled after the principles underlying the Congressional Budget Office and Government Accountability Office. A new ACIR could advise the executive and legislative branches on improving the intergovernmental operations and waiver processes of the White House and federal agencies, and advise those branches and state, tribal, and local governments of the intergovernmental consequences of U.S. Supreme Court rulings. It also could identify, study, and make recommendations on extant regulations found to be intergovernmentally problematic, the federal government’s 1,216 grants-in-aid, and House and/or Senate bills having intergovernmental impacts.

A new ACIR also would need more clout. It is one thing to deliver suggestions and another to be part of the legislative process. One way to add clout would be to require Congress to hold hearings on the ACIR’s recommendations.

What happens next for you?

The task force liked many of my suggestions. It will revise the bill and would like me to look at a new draft.

How about the ACIR?

There is a long way to go. It will be hard to add a new agency or budget line in the current fiscal and political climate, even though it would be small—about $3 million as part of a $4 trillion budget. I’m glad they are talking about it, but I am skeptical. Maybe the conversations will lead to other outcomes like regulatory revisions or provisions in other bills, if not a full-blown commission, although a new ACIR would be a very important acknowledgment by Congress of its need to play a positive role in restoring the federal-state-tribal-local partnership, as well as bipartisanship.