Common Ground

By Kathleen Parrish

Michael Newsome ’75 still can’t explain the circumstances surrounding how he came to Lafayette. He had received a full academic scholarship to Virginia Tech, the college of his dreams, when he was a high school junior. He never once thought about going anywhere else.

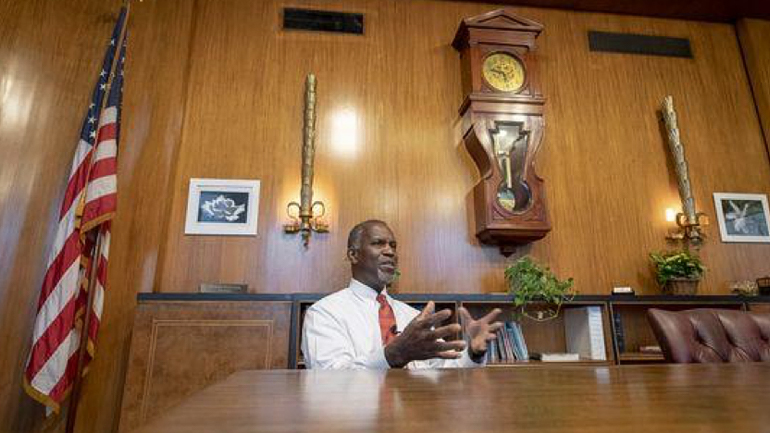

Michael Newsome ’75, cabinet secretary for Governor Wolf, at his office at the state capital complex in Harrisburg. (Photos: Paul Kuehnel, York Daily Record)

But then a man walked into the soda fountain at Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in Hampton, Va., where he was working behind the counter. It had been a slow shift, and Newsome thought he’d get a jump on his homework.

“What are you doing?” asked the man, whose name Newsome no longer remembers.

“Calculus,” he replied.

“You must be pretty smart,” the man said. “Where will you be going to college?”

Newsome told him.

“Have you ever heard of Lafayette?”

Newsome had not. He had never been outside Virginia. But when the man asked for his address so he could send him information about Lafayette, Newsome gave it to him. A few weeks later, he received a brochure in the mail, followed by an invitation to visit campus.

“They did a heavy job recruiting me,” says Newsome, who conjectures the College may have learned of his role in helping desegregate his Virginia high school in 1968.

At the time the mystery man had come calling at the soda fountain, Lafayette was looking to expand the racial diversity of its student population; it was also on the cusp of admitting women for the first time. The College wanted his help, he guessed.

A Good Match

Fifty years later, his reputation for bringing people together still stands. Just now he’s using it for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, where he serves as Gov. Tom Wolf’s secretary of administration.

The two have known each other for decades, from when Newsome worked as controller for the York Daily Record and Wolf owned his family’s building supply business in York County. Then in 2004, Wolf offered Newsome a job at the Wolf Organization, first as senior vice president and controller and then as executive vice president and CFO.

Until Wolf retired from the company after being elected governor in 2014, he called on Newsome every morning for an update on the cash position of the company. “When you have that kind of relationship, you’re close,” says Newsome. “My wife would joke that we had a bromance. I would call him and say, ‘What are you having for dinner?’ and he would say, ‘Spaghetti, but it could use some good wine.’”

Despite sharing a close personal and professional relationship, the two men came from different worlds. Wolf grew up with privilege, heir to a growing company.

Newsome was one of nine siblings raised in public housing by a single mother. He started working when he was 11, delivering newspapers to help feed the family.

He excelled in math at his segregated junior high. For ninth grade, he was selected, along with other academically gifted students at the school, to start the court-ordered desegregation of Hampton, Va., schools.

Newsome said his African American teachers worked hard to prepare students for the challenge of attending a formerly all-white school.

“They said there was no reason why we couldn’t compete academically and advised us to get involved in as many activities and social clubs as we could,” says Newsome.

Newsome joined the math club, chess club, yearbook staff, and student government. He also became co-captain of the football team his senior year.

The first two years were rough, he says, but by junior year he was running with the in crowd.

Then came a competition to see which class could raise the most money for the school. Newsome and his best friend created a computer program using punch cards to measure compatibility. Students paid 50 cents to fill out a questionnaire in return for names of their top five matches.

When the results came out, the entire school was in an uproar, recalls Newsome. He and his partner in the 1960s version of Tinder were called to the principal’s office. Turns out they didn’t ask participants to identify by race.

“He wanted to know what was going on,” says Newsome of the principal. “The black and white students were upset. Mixed-race dating wasn’t done.”

Their omission wasn’t intentional, but the two used the incident as a teaching moment.

“We ended up showing the administration that kids are compatible and have all these things in common, and race isn’t one of them,” Newsome says. “Believe it or not a few (mixed-race) couples started dating.

“The next day we were folk heroes.”

And the cute African American co-captain of the cheerleading squad whom he had been dating? She was first on Newsome’s list. Still is. Eloise Gray Newsome is now his wife of 44 years.

Can’t Say No

During his first term as governor, Wolf wanted Newsome to join his cabinet, but Newsome was leading the sale of Wolf Organization and “didn’t trust anyone else to do it,” he says.

A private equity firm purchased the company in May 2015, and Newsome retired in July of that year, but not for long. A few months later, Wolf appointed Newsome as a member of the Liquor Control Board, a part-time post he held until this January after Wolf won reelection and asked Newsome to serve as secretary of administration.

“Let’s do what we did at the Wolf Organization for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,” Newsome recalls Wolf saying. “I couldn’t say no.”

Bridge Builder

Newsome also couldn’t say no to Lafayette when he visited in 1970.

“They were trying to integrate the College and looking for kids who could compete on campus,” he says. “I had just done that in high school, and it was intriguing to me. I just fell in love with the campus and thought I could help.”

A math major, Newsome continued his penchant for getting involved in extracurricular activities, becoming an RA and a member in different clubs.

He briefly played football, but found the Division 1 competition “too painful” for his 180-pound frame, so he joined the band, playing trombone as he did in junior high and high school. He still got to run on the field, but only before games and at halftime.

As for building bridges between races, Newsome says one of his closest friends was white, and he hoped their relationship would inspire others to reach across the color aisle. Today, Newsome is still a master bridge builder, employing his talents for connecting across political aisles. He also credits his College years for laying the foundation for an interesting life.

“Lafayette was the best thing that ever happened to me,” he says. “It helped me continue to grow into the person I am today.