Restored artwork will appear in the Gemäldegalerie museum in Berlin and has been published in a German journal

More than 500 years ago, in a workshop in Venice, artist Antonio Vivarini and his assistants painted images of saints on a series of panels that would become part of a large altarpiece. Twelve of the panels eventually passed into the hands of private collectors, before being acquired by the Gemäldegalerie museum in Berlin in 1829, at which time they were separated. During the Second World War, the panels were stored in separate locations–some at a museum in East Berlin and others in West Berlin–and are in various states of disrepair.

More than 500 years ago, in a workshop in Venice, artist Antonio Vivarini and his assistants painted images of saints on a series of panels that would become part of a large altarpiece. Twelve of the panels eventually passed into the hands of private collectors, before being acquired by the Gemäldegalerie museum in Berlin in 1829, at which time they were separated. During the Second World War, the panels were stored in separate locations–some at a museum in East Berlin and others in West Berlin–and are in various states of disrepair.

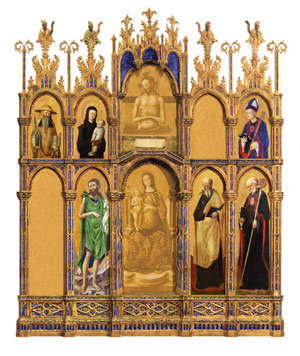

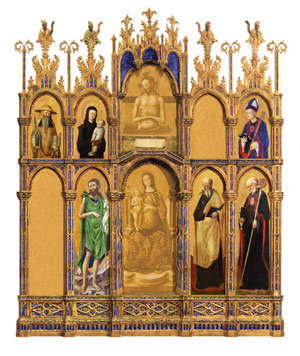

Now the panels can be seen together again, and in restored condition, depicted as they may have once appeared in position on the altarpiece. Lew Minter, director of the art department’s media lab, has produced digital reconstructions of two of the altar’s polyptychs (panel paintings) for Italian art historian Catarina Arcangeli, an external collaborator with Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie. Amanda Smith ’10 (Henderson, Nev.), a double major in art and economics & business, worked with Minter extensively on the project as an EXCEL Scholar.

“The opportunity to do these kinds of projects further enhances Lafayette’s position as a leader in the scholarly and academic communities of art and art history,” Minter says.

Arcangeli was working on a catalog of 15th century Venetian paintings for the museum when she became interested in these panels, which had long been ignored by scholars. She noted stylistic differences among the images of the saints, which led her to think that some may have been produced by a Vivarini collaborator somewhere in Eastern Europe. Therefore, it seemed likely that the panels belonged to two different polyptychs of the same altar.

Arcangeli turned to Minter for help in digitally restoring and reassembling the panels. She provided photographs and x-rays of the panels, which Minter and Smith digitally manipulated to remove damage and to restore colors to as close to the original as possible. The panels were fitted into a digital image of the frame, modeled after a frame from a Vivarini polyptych at the Vatican Museums.

“We can change the colors, we can brighten them, we can take scratches away, we can add and delete things,” Smith explains. “You have to do a lot of research on the artist, find out what his style was, what colors he used, and then you use that information to try to bring each piece back to life and make it whole. It’s not going to be perfect, obviously, but it’s our interpretation based on what we know and what we can do.”

The digital reconstructions will be exhibited at the Gemäldegalerie and were published among a broader discussion of the context of the polyptychs in the Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 2008 (Year Book of the Berlin Museums, published 2009). A detailed article focusing on reconstruction problems will be published, along with color reproductions, in a museum journal sometime soon, according to Arcangeli.

The pieces that Smith had seen only through computer images came to life when she traveled to Italy this past summer with Diane Cole Ahl, Rothkopf Professor of Art History, and Rado Pribic, Williams Professor of Foreign Languages and Literatures. A group of 26 students, including Smith, spent three weeks touring Rome and studying the artistic and literary culture of Italy. While in Italy, Smith was able to meet Arcangeli and see some of the pieces that she had worked on in person.

“This whole experience has broadened my range of capabilities as an artist and has expanded my creativity. I feel very fortunate to have been given the chance to assist such amazing artists and work on projects that are making a tremendous impact on the art world. EXCEL is a great way for students to get a look at the projects that will be presented to them in the real world,” Smith says.

“The purpose of my collaborations with art historians and curators is to expand the knowledge, not just of students who may work on the projects with me, but the scholarly community and the public in general, regarding masterworks that have been lost to the world through the visualization of scholarly research,” Minter says.

More than 500 years ago, in a workshop in Venice, artist Antonio Vivarini and his assistants painted images of saints on a series of panels that would become part of a large altarpiece. Twelve of the panels eventually passed into the hands of private collectors, before being acquired by the Gemäldegalerie museum in Berlin in 1829, at which time they were separated. During the Second World War, the panels were stored in separate locations–some at a museum in East Berlin and others in West Berlin–and are in various states of disrepair.

More than 500 years ago, in a workshop in Venice, artist Antonio Vivarini and his assistants painted images of saints on a series of panels that would become part of a large altarpiece. Twelve of the panels eventually passed into the hands of private collectors, before being acquired by the Gemäldegalerie museum in Berlin in 1829, at which time they were separated. During the Second World War, the panels were stored in separate locations–some at a museum in East Berlin and others in West Berlin–and are in various states of disrepair.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.