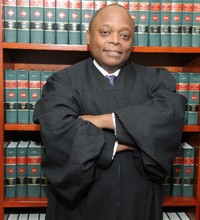

Judge Alvin Yearwood '83

In his 20 years of working for New York City’s criminal justice system, Judge Alvin Yearwood ’83 has seen his fair share of cretins and crime fighters. But even Yearwood was surprised when he walked into his Manhattan courtroom one morning last July and saw Superman sitting among the prostitution and robbery suspects, his red cape and blue tights shimmering under the fluorescent lights.

The Man of Steel — actually 23-year-old activist Maksim Katsnelson — had been arrested the previous night after lying down on a public sidewalk. When cops told him to move, the costumed Katsnelson ran into traffic, so the true crime fighters had to subdue him with pepper spray. It was the second time Katsnelson had been arrested in a week: The previous Thursday, he had been issued a summons for getting into a fight with a Batman impersonator in Times Square.

“When you walk into the courtroom and you see Superman sitting on the bench in full dress, you say, ‘OK, this may not be a normal day,’” says Yearwood, now acting justice in the Bronx County Supreme Court Criminal Division. “Sometimes you walk in and you just have to smile to yourself when you see things like that because — it’s New York.”

Unfortunately, Yearwood has been involved with characters more disturbing than fake superheroes. After graduating from Boston University School of Law and working briefly as an attorney, he volunteered for duty in the Bronx County District Attorney’s Office, where he prosecuted rapists and child abusers in the Domestic Violence/Sex Crimes Bureau. He considers that work some of the most important of his career, as he helped pioneer the use of DNA evidence.

“The use of DNA, which is now widespread, was in its infancy in New York as I was prosecuting the cases,” Yearwood says. “So, we did a lot of cases using DNA evidence. For instance, there was a case that was prosecuted in New York. The person was known as the Citywide Rapist. Over the course of a nine-year period, he robbed and raped women in Bronx, Manhattan, and Westchester. Most of his victims were in the Bronx, and that’s how I came into this. The only evidence that we had linking him to all of the crimes was DNA evidence, so that for me was one of the most important cases because this guy was on a nine- or ten-year-long crime spree after having been released from prison for a robbery of two women back in 1990.”

Yearwood also prosecuted other particularly heinous cases, including some in which children had been murdered by their parents. Sometimes, he admits, it was difficult to keep his emotions in check.

“It helped to have exceptional colleagues who you could discuss the cases with,” he says of his days as a prosecutor. “Very early on you have to learn to leave the work at work. You’re not always successful. There are times when you go home and there’s something you just can’t get out of your head because some five- or six-year-old kid told you something that their father or somebody else did to them that not even an adult should be talking about.”

Though he was the first criminal court judge Mayor Michael Bloomberg appointed to the bench, in 2003, Yearwood says he didn’t initially foresee himself in black regal robes.

“Other people projected me as a judge before I saw it,” he says. “People would say to me, ‘You’re either going to be a judge or you’re going to be the district attorney.’ As I went through the court system, I started observing judges more closely in terms of how they ran their courtroom and how they did their jobs, and I thought, ‘Yeah, I can do this.’ But more importantly, I started thinking about what it means to be a judge. What it means to be a judge is that you have great power and you have great discretion, but you can’t abuse either.”

Yearwood uses some of his discretion to help inner-city youth avoid punishment that could lead to a life of crime. His experience growing up as an African American boy in Brooklyn gives him insight into this at-risk population.

“My first obligation as a judge is to see that the defendant gets a fair trial and that the DAs get to present their case,” he says. “But I will say this: There are times when I have young defendants who come in front of me, who do not have a criminal record, and they did something stupid…Instead of saddling this person with a criminal record that could damage their life, in association with the lawyer for the defendant and the prosecuting DA, I try to fashion some sort of remedy that would help the person to get out of the position they’re in — some kind of community service. I try to say, ‘Look, I’m giving you an opportunity here. You have the opportunity to wipe the slate clean, and the only person that stands between you and jail is you.’”

Yearwood also helps young people outside the courtroom. As a board member of One Hundred Black Men in America, Inc., an organization dedicated to improving educational and economic opportunities for African Americans, he recently mentored a college senior who is now a first-year law student at Hofstra University. He also serves on the board of the Union Community Health Center in the Bronx, and has been a member of the Black Bar Association of Bronx County for 20 years.

His true passion, though, is the law, and prospective lawyers and defendants to his court should take heed: You’d better do what he says.

“If you would ask attorneys and other people in the courtroom about one of my [priorities], it’s for the person to be responsible,” he says. “If I tell you to do something, you need to do it.”

Let’s hope Superman listens.