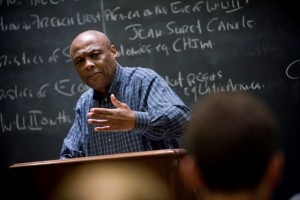

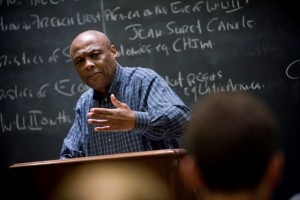

When John McCartney talks about the political struggles of the Bahamas and other Caribbean nations, he’s not reciting facts from a textbook. That’s because the professor of government and law has played a part in the history he teaches.

When John McCartney talks about the political struggles of the Bahamas and other Caribbean nations, he’s not reciting facts from a textbook. That’s because the professor of government and law has played a part in the history he teaches.

A citizen of the Bahamas, McCartney worked tirelessly to reform the Bahamian government after it gained independence from Great Britain in 1973. He was a two-time candidate for Parliament and helped form a political party that challenged the ruling majority of Prime Minister Lyden O. Pindling. He’s also met with the former leaders of Jamaica, Barbados, and Brazil as well as Cuba’s Fidel Castro.

“I put a real-life touch on what I’m teaching in class,” says McCartney, former head of the Africana studies program and government and law department, who started at Lafayette in 1986.

As McCartney grew up in Nassau, the Bahamas was still part of the British Empire and the colony was ruled by a white minority that controlled the banks, owned the stores, and employed its own. Black men could vote, but others got extra votes for holdings they owned on the various islands, and this benefited the elite white minority. (Women did not obtain the right to vote until 1963.)

But unlike in the United States prior to the Civil Rights Movement, blacks and white attended school together, prayed in the same churches, and played on the same sports teams. “Personal relations were more fluid between blacks and whites,” he says.

In 1967, Great Britain granted the Bahamas limited self-government and Pindling was elected the first black premier. Two years later he became prime minister.

“The country awakened to a new age and for the first 10 years significant strides were made,” says McCartney, who left the Bahamas in 1961 to attend college and grad school in the U.S. In 1970, he earned a Ph.D. in political science from the University of Iowa and began teaching at Purdue.

While in the U.S., McCartney kept a close eye on the political situation in the Bahamas and was even offered several jobs in Pindling’s administration, which he turned down. Eventually, McCartney became critical of the prime minister and his efforts, he believed, to thwart the democratic process. So in 1972, while teaching political science at Purdue, McCartney helped form an opposition party in the Bahamas called the Vanguard Party and served as chairman. It was the only party that addressed not only race, he says, but the fundamental issues of society.

“People who were critical of the government lost their jobs and victimization became the order of the day,” he says. “The open society became more and more closed.”

Then in 1979, he decided to return to his island home and work full time for political change. For three years, the Vanguard Party campaigned vigorously throughout the country, holding outdoor meetings and cookouts and advertising on the radio and television. In the 1982 election, 35 Parliamentary seats were up for grabs and the Vanguard Party fielded 25 candidates.

“We got good support during nonelection time,” says McCartney. “But during election years, we were at one hell of a disadvantage.”

A patronage system rewarded jobs for votes and it wasn’t unusual for the party in power to throw lavish parties for supporters as far away as Miami, McCartney says. Conversely, opponents were vilified, fired from their jobs, and denied scholarships to attend college in the U.S.

The Vanguard Party refused to pay for votes and although it earned the respect and admiration of many citizens, McCartney says, not one of its candidates won a seat.

The loss was devastating to McCartney and the party disbanded in 1986, unwilling to put its supporters through any more hardship and intimidation. A few years later, McCartney accepted a job at Lafayette. He doesn’t regret his political involvement.

“I don’t know if I’d feel complete if I hadn’t tried,” he says.

McCartney is still passionate about politics, but now directs his energies toward enlightening students. “I tell them democracy in other countries is not simple,” he says.

He still has political ties with his homeland and occasionally returns with students for tours of Parliament and interviews with island leaders, who talk fondly of McCartney’s valiant efforts to bring reform.

It’s an experience he couldn’t offer before Lafayette because he had too many students in a class. At Lafayette, he says, he can tailor his teaching to students and really get to know them as individuals.

“Here, we can take students to the Bahamas, which makes learning a lot more effective,” he says.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.