Perhaps you’ve read the book or seen the movie Like Water for Chocolate. In one small village in Honduras, it’s just the opposite: Villagers are learning to grow a variety of crops, including cocoa, with the goal of earning an income that will help them maintain their new water system.

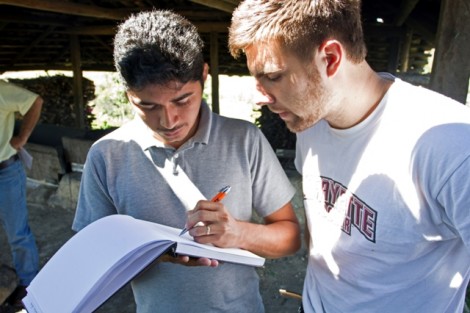

Images by Jack Fedak ’13

Since 2003, Lafayette’s chapter of Engineers Without Borders has been working in El Convento and other communities in the poor Yoro region of Honduras to install clean water systems and provide other infrastructure improvements.

Once those systems are in place, the communities need to be able to maintain them. And to do that, they need to find ways to bring in income. That’s where Lafayette’s Economic Empowerment and Global Learning Project (EEGLP) has stepped in.

EEGLP recently worked with the villagers of Lagunitas, Honduras, to plant more than 30,000 coffee plants to boost the local economy.

Now they are helping El Convento establish its own cash crops, such as cocoa.

“Our goals for this group are to help the village thrive economically and socially on their own efforts of cultivating the land and reaping the various fruits from their harvests,” says EEGLP faculty adviser Anuradha Ghai, lecturer in economics.

Still in the early stages, the project has so far put the villagers in contact with XOCO [pronounced sho-koh], a Nicaragua-based producer of high-quality cocoa beans. The company works with farmers in Central America to establish cocoa-growing operations as a means of lifting communities out of poverty. Over spring break, the students went down to Honduras to meet with XOCO representatives and the villagers.

Working with XOCO will allow El Convento to empower itself through cocoa entrepreneurship. An XOCO representative recently met with the villagers to discuss the potential for growing cocoa on their land.

“The group in El Convento knows very little about cocoa and was unaware that they have the ideal geographical conditions for cocoa farming. In that respect, it was important to see how the farmers in El Convento reacted to the opportunity they had just discovered,” says EEGLP project manager Richie Durham ’11 (Braintree, Mass.), a double major in economics and Spanish.

EEGLP will provide the financial and technical capital necessary for the group in El Convento to prepare the terrain and purchase the initial cocoa plants. This critical step will occur this summer at the beginning of the rainy season. Within the next few months, the El Convento group will be signing a XOCO’s buyer-seller contract and receiving training.

The group is working out terms of a contract regarding labor, land use, distribution of profit, conflict resolution, and other issues.

“The key ingredients for success will be our ability to coordinate the initial relationship between XOCO and the vilagers in El Convento, a complete assessment of irrigation needs, and the ability to help the group further develop the collective will necessary for collaborative production,” Durham says.

Because they are essentially starting a new business in the community, there is a lot of upfront work to be done. Still ahead is the need to do extensive research on best environmental practices and other agricultural aspects, price trends for the crops the community will grow, and many other factors that will determine whether the undertaking succeeds. The students will travel to Honduras again in June or July to help with the crop planting and other start-up issues.

According to Luke Calvano ’12 (Eastampton, N.J.), an economics and policy studies double major, the community of El Convento, not EEGLP, must be the driver of the project for it to succeed. It’s the philosophy of teaching a man to fish rather than giving him a fish.

“We don’t want to march into a community and start planting seeds. We want the group to own and nurture the projects. That way they can recognize their value and link it to their livelihoods,” says Calvano. “So much more can be achieved when the community members of El Convento completely buy in and dedicate themselves to these projects.That’s what makes them work, and that’s what makes them last. If they know how to operate the machine that is their business and community, they won’t need us anymore, and that’s the whole point.”