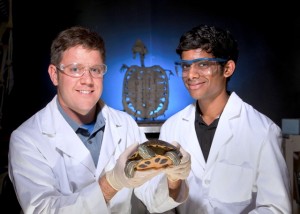

James Dearworth, associate professor of biology, and Brian Selvarajah ’12 analyzed visual pathways in vertebrates using the turtle as a model. Dearworth is one of 60 faculty members whose research deals with health and life sciences.

Tackling complex national and global problems requires knowledge from many different disciplines. No one science can provide a solution; expertise and input from physicians, scientists, politicians, lawyers, and policy makers is needed.

At Lafayette, the new minor program in the health and life sciences provides just the intellectual and interdisciplinary education students need to bring problem-solving ideas together in a future career.

“Today, the world’s most complex problems lie at the intersection of two fields,” explains Robert Kurt, associate professor of biology and chair of health and life sciences. “This minor prepares students to solve these problems.”

The creation of the program is a part of a larger picture—Lafayette’s strategic plan. A key objective in the plan is to establish a high-caliber, integrated center for the life sciences that will house the biology, computer science, and geology departments, as well as interdisciplinary programs in health & life sciences and environmental science.

According to Mary Roth ’83, associate provost for academic operations, a main goal of the health and life sciences program is for students to establish connections among different areas and integrate information.

In order to ensure its success, Roth and an ad-hoc committee applied to participate in a three-year Project Kaleidoscope (PKAL) program, “Facilitating Interdisciplinary Learning in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) Disciplines.”

From left, Brian Peacock '12, Laurie Caslake, associate professor and head of biology, Arthur Kney, associate professor and head of civil and environmental engineering, and Annie Mikol '13 are using bacteria to improve the water quality of wetlands.

“Through PKAL we were able to connect with faculty at other institutions who were working on similar initiatives,” says Roth. “Those conversations helped us determine our goals and objectives, which in turn assisted us in designing the best program to meet those outcomes.”

The committee’s hard work paid off. Lafayette’s case study was chosen as a model of “what works” at PKAL’s national convention in 2010.

What is working now for Carly David ’13 (Concord, N.H.), who is majoring in biology with a minor in health and life sciences, is the ability to learn about current, groundbreaking research. Through her experience enrolled in the Interdisciplinary Seminar Series, a requirement for the minor, Carly met six researchers in fields such as nanotechnology, investigative journalism, and biochemistry.

“Not only were we able to meet brilliant scientists, but we were able to get to know them on a personal level,” says David. “It was interesting to discuss their experiences in school and to learn about what shaped their career choices. We learned that both education and experience played a pivotal role.”

It is this type of small-class interaction and exposure that prepares Lafayette students to share ideas and take risks, experiences that will ultimately shape their future. Biochemistry major Alec Eidelman ’13 (Marblehead, Mass.) completed a 10-week independent study last summer with Kurt. A $190,000 grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute is fueling Kurt’s research on the body’s immune response to cancer, specifically how to make the body recognize cancer cells better.

“The final requirement for students enrolled in the health and life sciences minor is to take either a capstone course or to write an interdisciplinary honors thesis, bridging research from two different disciplines involving life sciences and health,” Kurt explains. “We want to provide students with a well-educated idea of what they can accomplish. If they have not performed research themselves it is hard for them to understand what is feasible and what is not.”

The minor was designed to have broad appeal to students majoring in humanities and social sciences as well as those studying natural sciences and engineering. Students can pursue projects bridging biology and psychology, neuroscience and art, or computer science and ethics, and Kurt is one of 60 faculty from 15 different departments who plan to be involved in interdisciplinary research though the minor. It is structured so that students experience the range of disciplines that impact decisions in the life sciences today.

“The fact that the minor is not just focused on science is extremely valuable,” explains Chun Wai Liew, associate professor and head of computer science, who serves on the advisory committee for the minor and was involved in the PKAL project. “This minor helps students view the world and health/life science problems through a multi-disciplinary lens. Students will be better prepared to develop more comprehensive solutions that take multiple factors into account.”