There is a persistent notion that Africa is a benchwarmer of sorts in the game of world affairs, an untouched land where time stands still. What a group of 17 students learned during a January study-abroad course—Religion, Society and Change in East Africa—is the fact that Africa has always been a central player in the world system.

This is the first year that Robert Blunt, assistant professor of religious studies, and Steven Belletto, assistant professor of English and chair of American studies, have offered the course, which immersed students in the cultural and religious dynamics of East Africa. Belletto and Blunt, who has an affiliated appointment with Africana studies, see the trip as part of the College’s expanding commitment to global learning. The course featured two segments: a coastal portion where students stayed primarily in Lamu, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, studying Swahili language and culture, and a Maasailand portion in southern Kenya where they learned about Maa culture and social and religious change.

Africa has been subject to problematic representations by Westerners for centuries, and one focus of the course was to help students think critically about such representations. The prevailing stereotype of the Maasai in particular is that they are “Noble Savages,” close to nature and outside modern society and government constraints, a notion introduced in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries and made popular by media representations like the film Out of Africa. Perpetuating that stereotype is big business, especially for the safari industry.

But students learned that East Africa is indeed a culturally and economically relevant place. Blunt points out that the Nairobi real estate market is one of the strongest in the world, and in recent years, East Africa’s geopolitical importance has transformed once again as Eastern development partners like China and Japan are helping to build a deep-water port on Kenya’s northern coast to access South Sudanese oil.

“We really wanted our students to do the hard intellectual labor of deconstructing these stereotypes and see that these particular people are not reducible to these stereotypes,” says Blunt. “We wanted them to learn how Maasai society organizes itself historically and contemporarily and how they think of themselves as people in the contemporary Kenyan nation state.”

“It’s something we emphasized throughout the course,” adds Belletto, who used his background in literary and cultural studies to encourage students to explore how representations of Africa have often distorted the reality of daily life there. “Maasai society is a robust and complicated one that is very much a part of the 21st century.”

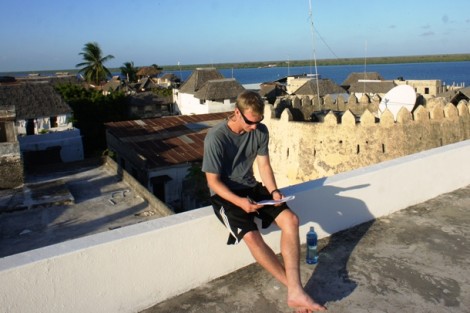

Students spent each morning on Lamu Island in Kiswahili class for three hours with their language coordinator, John Gitau Kariuki. In the afternoons, students led class discussions on readings about coastal history and the region’s dominant religion, Islam. They also had free time to explore Lamu and write in their field journals.

In Melepo, a region in Maasailand, the group learned about Maasai and Samburu (a northern group of Maa speakers) culture through “walking lectures” led by Michael and Judy Rainy, Blunt’s mentors when he was an undergraduate at Lewis and Clark College, and Pakuo and Larale Lesorogol. Much of their learning came from long discussions with Samburu and Maasai elders, who visited with the group to answer questions the students had based on their readings and observations. Female students also met with Maasai women separately so they could ask questions about issues that the women would only feel comfortable discussing without the presence of men.

Learning from the Rainys, who have lived in Kenya for nearly 50 years, and sharing discussions with Samburu and Maasai elders helped neuroscience major Morgan West ’13 (Huntington Beach, Calif.) see how East African society has evolved over time in response to societal and global change. The experience turned her definition of progress on its ear.

“We don’t often think of the people of this globe as all living in the same moment in history because our understanding of advancement and progress as a society is so linear,” she says. “This makes it difficult for us to imagine that while we categorize some foreign places as being less developed, they are really just developed differently.”

As a religious studies major, Evan Backer ’14 (Spring Lake, N.J.) says his first educational priority is learning about religions in context, and the religious diversity of East Africa makes it the perfect place to do just that. Also, Backer is considering post-graduate study in anthropology so the daily practice of keeping a field journal and making notes on the go gave him great insight into the professional life of an anthropologist.

“The difference in culture provided such a rich environment for learning,” he says. “We learned about the Swahili, about Islam, and about the Maasai, who are not Muslim, as well as local politics and economics, which I wasn’t expecting. It was wonderful learning the ropes of pastoral society in Maasailand.”

Visiting a predominantly Muslim region like Lamu town and Shela village, both located on the island of Lamu, was a welcome change of pace for Tahir Basil ’13 (Philadelphia, Pa.), who for the first time found himself in a place where the dominant religion was his own. The locals recognized Basil, a double major in economics and Africana studies, as a fellow Muslim, taking him on visits to the many mosques that checker Lamu’s urban landscape.

But Basil enjoyed the homestay experience in Melepo the most. Students stayed with Maasai families for a two-night homestay in accommodations that are quite different from American homes. Designed for security and warmth, many Maasai homes are constructed of wood and cow dung with low ceilings. As a pastoral people, much of Maasai life is centered around shared cattle corrals outdoors; homes simply provide a place to sleep.

“It was most interesting to immerse ourselves in the culture rather than stay secluded in nice resorts away from the people who were the most important in our ability to learn as much as possible about the history and culture,” says Basil. “My homestay was a phenomenal, once-in-a-lifetime, eye-opening experience.”

The students certainly have carried what they learned back to College Hill. West was so intrigued by the study of Kiswahili, for instance, that she is organizing weekly sessions with Blunt, who is fluent in the language, for interested students to continue their study.