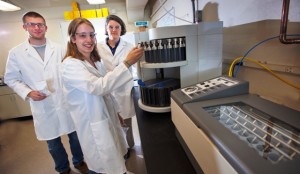

Hollis Miller ’15 (Fort Washington, Pa.) is in the basement lab of Van Wickle Hall, extracting organic material from mud deposited on the ocean floor millions of years ago. She inserts a steel cell, which looks like a mouse-size dumb bell, into a machine called the accelerated solvent extractor.

Chris Kelly ’13, Hollis Miller ’15, and Professor Kira Lawrence in Van Wickle Hall

“A fancy coffee pot is how Kira describes it,” she says, referencing Kira Lawrence, associate professor of geology and environmental geosciences, who recently coauthored a paper using this methodology that was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation and published in Nature, one of the most prestigious science journals in the world. “As this thing spins, it will pump chemicals into the cell and extract organic material from it.”

A fraction of these organic extracts will then be used to generate sea surface temperature estimates from the Pliocene, an epoch that began roughly 5 million years ago. The samples Miller and Lawrence are studying were drilled from the ocean floor in the Southern Hemisphere, which has been largely ignored relative to the Northern Hemisphere, where significant climate research about the Pliocene epoch has already been conducted.

“We want to generate climate records from the Southern Hemisphere to see if the two hemispheres responded similarly to changing climate,” says Miller, a geology and anthropology & sociology double major.

It’s a continuation of research conducted by Lawrence to help scientists better understand changes in today’s climate.

For the paper published in the April 4 issue of Nature, Lawrence and her collaborators from Yale University, University College London, University of Hong Kong, San Francisco State University, and University of California, Santa Cruz also compiled records of sea surface temperatures generated from materials preserved in ocean sediment cores. Their data synthesis revealed three important temperature patterns during the warm period of the Pliocene: 1) that maximum ocean temperatures were about the same as now; 2) that unlike today, across the tropics waters were fairly uniformly warm; 3) that the differences in temperature between high latitudes and the tropics were much smaller.

The Pliocene is considered one of the best analogs for determining future climate conditions because it was the most recent time when the concentration of carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere was similar to what it is today, and global average temperature was about 3 degrees Celsius warmer than now, a magnitude that matches projections for the amount of warming that should result from human-induced climate change by the year 2100.

“Despite what seems to have been marginally different climate forcing during the Pliocene, the temperature patterns on the surface of the Earth were quite different compared to now,” says Lawrence. “There has been a tendency to focus on changes in global mean temperature as a means of comparing how similar climate was in the past to what it is now. What our study shows is the potential for climate patterns to be markedly different in a world that was not that much warmer than today’s.”

If that’s the case, Lawrence says, we could see significant changes in temperature and precipitation patterns in the not-too-distant future.

The team of scientists then used climate models to explore whether any of the previously proposed mechanisms for the warm conditions of the Pliocene could reproduce the three characteristic features of the Pliocene temperature pattern. Their model experiments revealed that no single mechanisms could account for the observations. They conclude that in addition to a build-up of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, other factors are necessary to explain the warmth and climate patterns observed during the Pliocene.

“Understanding the conditions and the processes controlling the climate of the Pliocene is potentially important for understanding future climate changes,” says Lawrence.

Chris Kelly ’13 (Boyertown, Pa.), who previously was awarded a Goldwater scholarship and recently won a Fulbright scholarship to conduct sea level research in Durban with Dr. Andy Green at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, off the coast of South Africa, is completing an honor’s thesis on the Miocene epoch, which began nearly 23 million years ago, under Lawrence’s tutelage.

“By identifying the mechanisms at play within the climate system, we can develop a clearer sense of what to expect as the climate system responds to human-induced changes in the composition of the atmosphere,” says Kelly, who participated in the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s prestigious summer student fellowship program last summer.

He says before heading to Woods Hole, Massachusetts for the program at the start of last summer, he was nervous about whether he’d be able to keep pace with other student fellows from Ivy League institutions during the summer fellowship, but thanks to Lawrence he was more than prepared.

“I had just spent three months in rural Namibia essentially incommunicado, so the whole idea was somewhat intimidating. Cape Cod was a complete 180. As it turns out, I wasn’t behind the eight ball at all,” says Kelly, a double major in geology and international affairs. “If anything I felt more prepared. Kira’s courses were tailored to cultivate the skill set necessary to succeed in climate science and paleoceanography. She is a gifted teacher and a thoughtful mentor. No one could be more fiercely supportive than Kira.”

In the meantime, Miller is spending the summer as Lawrence’s research assistant through the EXCEL Scholars undergraduate research program, using sediment from the South Pacific to reconstruct past changes in southern hemisphere climate.

“Kira really wanted me to take ownership of this project,” she says. “It’s one of the reasons I came to Lafayette—to do research as an undergraduate.”

3 Comments

Wow this is impressive, Hollis. I can’t wait to hear more about it in person before too long. I love learning things I never even knew existed.

Naomi

Kudos and best wishes to all!

This is a miniature chemical engineering unit. That’s really old dirt, Hollis.

Comments are closed.