Nancy Waters shares three things with all of her students. One, energy flows and nutrients cycle. (“Energy is always one direction, but it moves by virtue of nutrients which can be recycled either short term or long term.”) Two, everything comes down to food and sex. (“If you can’t propagate your genome, everything is toast.”) And three, put $2,000 in an IRA the day you graduate. (“Because of the nature of exponential growth.”)

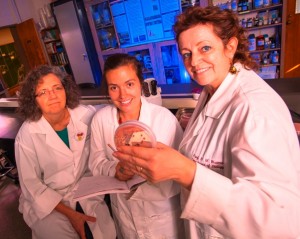

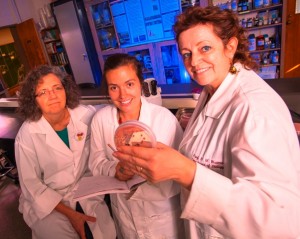

Laurie Caslake, associate professor of biology, Lindsay Marko ’14, and Nancy Waters, associate professor of biology, with a culture they collected from the Delaware River and Oughoughton Creek.

Waters, associate professor of biology, has a lot of energy and, if students work hard and keep up, they’re in for an exciting ride of discovering the natural world.

For instance, students in her Advanced Aquatic Ecology course may find themselves on a pontoon boat—Waters’ floating lab—completing small-scale research projects along Merrill Creek Reservoir near Washington, N.J. At least two of her students have presented their classroom research at conferences.

The six students she advised on a two-semester Technology Clinic project referred to themselves as “The A-fish-ionados.” They worked to identify a base market for local farm-raised rainbow trout and to maintain trout quality and a healthy pond ecosystem for their client.

An interdisciplinary approach

This summer, EXCEL Scholar Lindsay Marko ’14 (Doylestown, Pa.), a biology major, is studying mercury-resistant bacteria in a section of the Delaware River and Oughoughton Creek. The researchers believe a coal ash spill in the area a decade ago may be contributing to the presence of these bacteria (coal ash contains metal contaminants).

Marko’s work is funded by the David M. Nalven ’88 Summer Research Fellowship, a scholarship established by his family and friends after his untimely passing to honor the impact that working in Waters’ lab had on him. The fellowship has funded nearly 30 students, more than half of whom have worked under Waters’ guidance on projects that include how pesticides affect monarch butterfly development, how disturbances in lake littoral zones impact vegetation patterns, and the role that stream invertebrates play in processing stream debris.

Marko’s project combines ecology with molecular biology, an interdisciplinary endeavor that, Waters says, was uncommon when she joined the faculty 27 years ago. Waters also is seeking a student to continue research begun by biology graduates Chelsea San Filippo ’13 and Will Giammattei ’13 on a beaver dam’s impact on aquatic invertebrates and water ecology in Upper Merrill Creek.

“The College encourages and embraces multidisciplinary approaches to problem-solving,” Waters says. “Science needs to be more interdisciplinary to reflect our changing knowledge base. We used to teach in a way that was only content driven, but it’s much more beneficial to teach content and then give students the tools to ask questions and answer them.”

Teamwork

Keeping abreast of the latest scientific trends as well as the latest pedagogical trends is one of the reasons Waters was the first woman in the sciences and engineering to win the College’s Student Government Superior Teaching Award. This fall, she and Laurie Caslake, associate professor of biology, will team-teach a capstone course in biology focused on problem-based learning. They will present the challenge of malaria and cede control of the learning process to their students, which Waters finds both exciting and terrifying. Working in teams, students will draw on all they have learned in their four years at the College to tackle everything from genetically engineered mosquitoes that do not carry the disease to distributing mosquito nets within cultures that believe the nets lead to infertility.

“I’d be willing to team-teach a course with any of my colleagues. These are good people to work with—we have different styles but the same core values,” says Waters. “I think there is a duty and obligation to remain not just current on scholarship but innovative in how we approach our material. That kind of teaching pushes me to the edge of my comfort zone, but it’s worth it.”

A love for poetry and theater

The edge of her comfort zone is familiar territory for Waters. She is working on a collection of poetry, not a surprise given that her Ecology class was among the first writing-enhanced natural science courses at the College. It is vitally important, she says, for scientists to communicate their work clearly to non-scientists. While not nature poems, the 16 completed pieces use imagery from the natural world and science. Teaching at Lafayette allows Waters to be a student, seeking advice and feedback from colleagues like Suzanne Westfall, professor of English, and Lee Upton, professor of English and writer-in-residence.

Waters also is passionate about theater and jokes that she has been doing performance art in the lab her entire career. The arts discipline her emotions just as science disciplines her brain, she says. She was involved in College Theater’s dramatic reading of Hear Me Roar: First Among Men in celebration of Women’s History Month and the 40th anniversary of co-education at Lafayette. Far earlier in her career, she choreographed Westfall’s production of The Canterbury Tales, performed in a main stage production of Three Penny Opera, and played the title role in a Marquis Players production of Evita.

How to ask good questions

As the health professions adviser and co-chair of the Health Professions Advisory Committee, Waters advises students interested in healthcare careers on portfolios, medical and graduate school applications, and career exploration. Helping students make important decisions about their futures based on the best, most current information they can find is exactly what she strives to do in the classroom—teach students how to ask good questions.

“Students are not a blank slate; they come with an enormous complexity of worldviews and perspectives,” she says. “I want to facilitate them to ask good questions, not to be afraid to ask questions, and to figure out what makes a question good. It is as important in ecology as it is in government or a courtroom.

“Learning ought to be enjoyable. If my goal is to make students more thoughtful, then I have to work backward from the goal to figure out what it takes to achieve that. Am I willing to do what I need to do to get there? Most days, I wake up and I’m willing to do it.”