Paterson Joseph sat in front of a portrait projected on a screen in a Lafayette classroom and told students and faculty of his ruse.

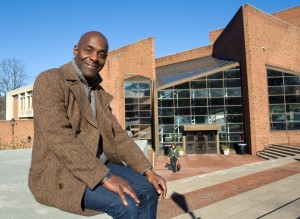

Paterson Joseph outside the Williams Center

The British-born actor had spent a decade learning to become the man in the painting – the historical figure Charles Ignatius Sancho. Joseph read letters Sancho wrote in the 18th century, pored over what others had written about him and rehearsed his voice. Joseph hopes it will be enough to convince another audience – this time a crowd at 8 p.m. Dec. 14 at the Williams Center — that Joseph is none other than the first black man to vote in an election in England.

But when Joseph finished writing his one-man play several years ago, he discovered he’d been Sancho all along.

“I guess that’s the creative process, right?” he said, grinning at the 20 or so students who gathered for Monday’s brown bag lunch. Joseph, 51, is known to American audiences for his films and most recently a role in HBO’s The Leftovers.

He compiled his play, “Sancho: An Act of Remembrance,” piecemeal, reading letters and histories between acting gigs. Joseph first encountered Sancho in a portrait in “Black England: Life Before Emancipation” by Gretchen Gerzina. He’d been looking for an historical figure to play.

In the painting, Sancho is dressed as an 18th century aristocrat. But unlike similar paintings Joseph had seen from the period, Sancho was a black man.

“I thought maybe it was another satire,” he said. “But it was 1768.”

Curious, Joseph began his research. He discovered a boy born on a slave ship and raised a house servant until his emancipation. Sancho, the man, was a prolific author and composer, a liberal Whig, who one day purchased a grocery store, thereby obtaining the property-owner qualification required to vote in the era of King George III.

Joseph knew little of black history in England, even though he’d lived it. His working-class parents were born in St. Lucia and immigrated to London. His love for his craft came from play acting with his sisters. Overcoming shyness and negative perceptions about his own intelligence, Joseph obtained a business degree and tried being a chef until he auditioned for Shakespeare.

Meanwhile, British schools taught little about the subject. “I didn’t even know about 1948,” he said, the year the SS Windrush brought the first postwar people from the Caribbean.

Now, local ignorance is fading. “Today [in England] black history is a thing,” he said.

In 2010, as he prepared to add his own play to the canon, a friend told him, “My God, you’ve written an autobiography. It’s not his life, really. It’s your life.”

“I hadn’t occurred to me,” Joseph said. But he couldn’t escape the similarities. Sancho struggled for his son as Joseph struggles for his own. Like his subject, the author is stridently political. “Wanting a family and to be stable and to make a living, despite the fact that he’s got these other dreams and desires. That’s kind of my story,” Joseph said.

So the history he’d sought to write is a modern, after all. And though the chords it strikes are personal, they have broader implications.

“It’s the ending, really,” he said. “When he has to vote.” For Sancho, voting was an act against the disenfranchisement of his race, Joseph said. For women who didn’t obtain the right until the 1920s, the moment was liberation. For Joseph and, perhaps, for you, it’s a struggle against the apathy of the hour.

“Do it. It’s your right,” he said. “The setting is the 18th century, but it could well be today.”