Prof. Paul Barclay's new book examines Japan's 50-year occupation of Taiwan.

By Katie Neitz

By Katie Neitz

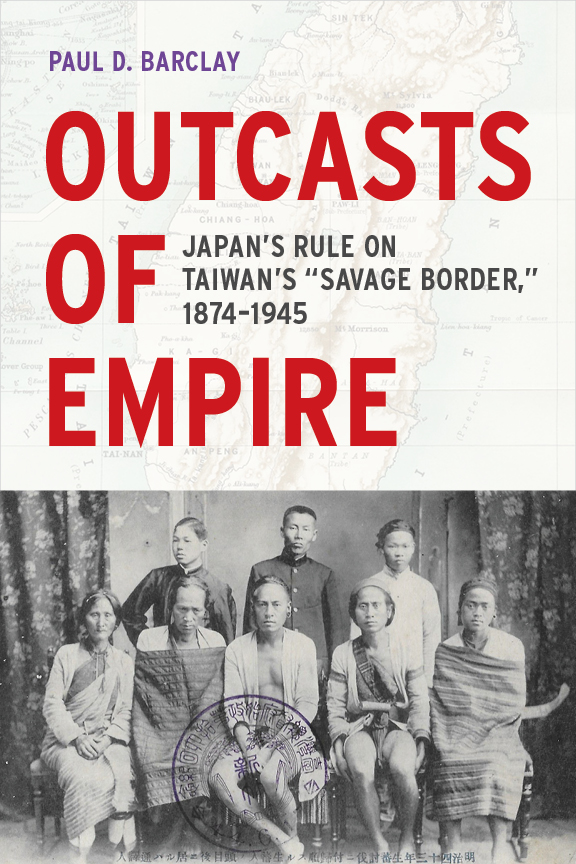

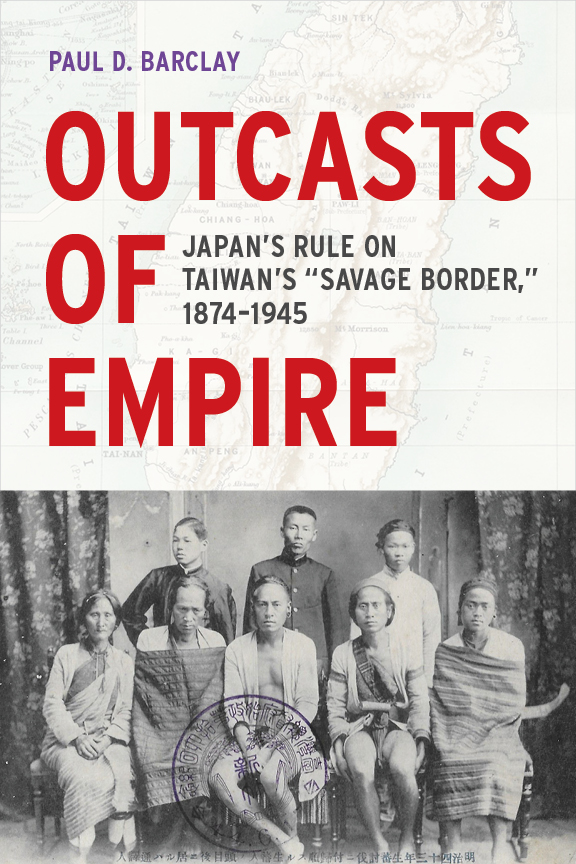

When it comes to the history of the Japanese Empire, one event—Pearl Harbor—overshadows all others. (A day that lives in infamy, indeed.) But in his new book—his first—Paul Barclay, professor and chair of Asian studies, turns back the clock to focus on an earlier formative period of Japan’s modern history: its 50-year occupation of Taiwan. Outcasts of Empire: Japan’s Rule on Taiwan’s “Savage Border,” 1874-1945 (published by University of California Press) examines the impact of Japanese colonialism in Taiwan—specifically, how the capitalist empire collided with indigenous peoples. Here, Barclay talks about the book, his research travels, and how the real challenge of writing a book is deciding what should land on the editing-room floor.

Why did you write Outcasts of Empire?

“The goal of the book is to take frontier wars and rebellions against the empire and to put them into a larger story about the development of the international nation-state system. What is it about nation states that makes indigenous peoples more visible and more politically salient at the same time that nationalism and nation-building diminish indigenous living space and life chances? There’s this double-edged sword quality about the international system and indigenous peoples, and I wanted to give that a historical treatment. It’s almost only anthropologists who study people who don’t have states, and I wanted to give a historian’s view.”

Barclay (right) with Taiwanese author and researcher Den Shian-yang, a pioneer in the field

How long had this been in the works?

“Eleven years. It wasn’t 11 years of uninterrupted toil, but it was still intense. I went to Taiwan about 10 different times and was all over that island, including up into the mountains. And I’ve been to Japan for short visits more times than I can count; I lived there during sabbaticals and summer research periods as well. Japanese is my primary research language, and I studied Chinese for a year at the survival level. Through the EXCEL Scholars program at Lafayette, I’ve had five students translate Chinese for me, which made the book much better.”

Why this subject matter?

“I taught English in Japan after college in 1992. I was there for a year, and then I went on to get my Ph.D. in Japanese history and American studies. I was always interested in American history, and then I discovered that Japan also has this unwritten history of a complicated relationship with indigenous peoples, and so I wanted to open that field up. I’m glad I did.”

Barclay (first row, third from left) with the Taiwan-Japan Indigenous Peoples Study Group in 2014

Did you uncover anything that surprised you?

“One of the biggest surprises for me was how diligent Japanese imperialists were in trying to maintain records of face-to-face relations with hundreds and hundreds of indigenous leaders for the first decade of colonial rule. They have a pretty robust paper trail for their attempt to make indigenous peoples into citizens. We often think of indigenous peoples as victims of asymmetrical warfare—you could think of the Trail of Tears or Wounded Knee—these various wars where mechanized, powerful armies rolled over disadvantaged peoples. But what I studied occurred high in the mountains of Taiwan, and it seemed to be more like an Afghanistan situation where terrain and local traditions of self-defense made these people formidable enemies and the war itself nearly interminable.”

What are you hopeful your book can achieve?

“I hope that a history about a relatively unknown place such as Taiwan can illuminate important processes that find echoes in different places and times. The example of Taiwan under Japanese colonialism provides a rich, complicated, and well-documented case study that can be applied to other instances of global colonization, such as those in South America and Southeast Asia. Wherever you are doing indigenous studies, I think the Taiwan case has something to teach. I hope it also gives a broader perspective of the Japanese empire. Japan is not often thought of as a full-blown member of the ‘imperialist’s club’ dating back to the 19th century. When people think of Japan, they often think of World War II and the Pacific War and things that happened in the 1930s and ’40s, but my study focuses on the 1890s and early 1900s, when colonialists were redrawing the political boundaries of the world map.”

Barclay’s research travels led him into mountainous regions of Taiwan

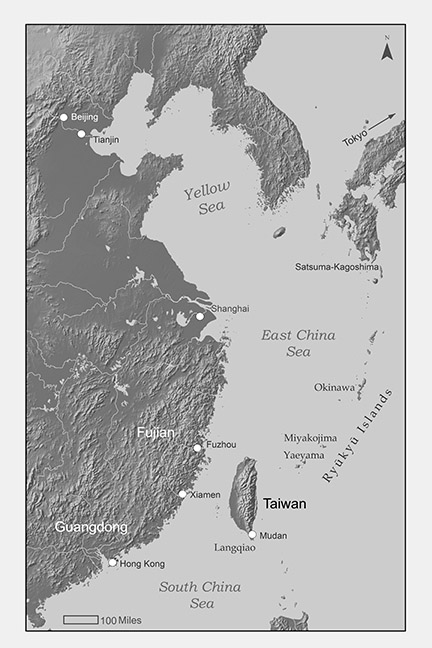

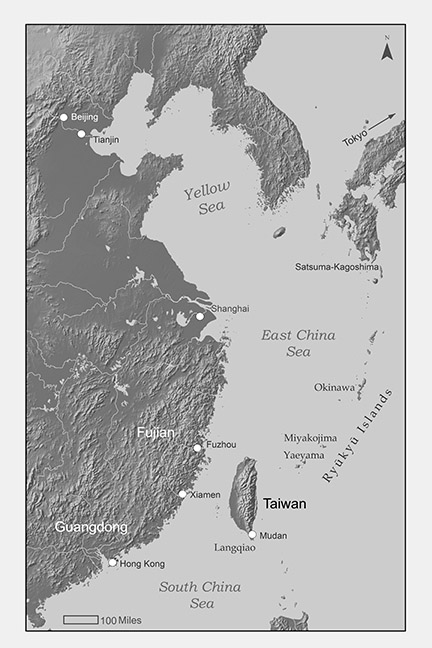

How did you obtain the images and maps in the book?

“I’m a digital archivist and editor of a website called East Asia Image Collection, which the Skillman Library has supported, funded, and sustained. I buy photographs in used bookstores and flea markets in Japan, or I go on Japanese auction sites. Several collectors have also made donations to the site. The library digitizes that material and makes it accessible to the world. Because the library does that, I was able to use a lot of those images in my book. That was something of a coup to have 69 illustrations, including six maps, which John Clark of Digital Services made for me. The book wouldn’t have been possible without that support. I think the visuals are so much a part of the story. They provide evidence of the transformation of rural people into indigenous tribes during the period of Japanese colonialism.”

What was the best part of the book project?

“All the people I’ve met. I love that I have a huge global network now. There are dozens of scholars who are very interested in this material, and that’s very exciting. A project like this enables you to meet people from all over the world who want to test these ideas and build knowledge.”

Prof. Paul Barclay’s favorite map featured in his book. It’s one of six created by Skillman Library’s Digital Scholarship Services.

What was the most challenging part?

“It took me 11 years because Outcasts of Empire is a 300,000-word book that I had to boil down to 110,000 words. My effort isn’t reflected by what I put in there—it’s what I didn’t put in there. The excision of what doesn’t belong in the book is what takes so long. What is the essence of this thing? What needs to be known? And what doesn’t need to be known? Look at this book [pulls down a very thick volume off his bookshelf]. What am I going to do with this? This is scary. Am I going to quit my job so that I have time to read all of this? Writing 20 pages is easier than 10. Writing 10 pages is easier than five.”

What’s next?

“The general editor of my book series, called Asia Pacific Modern, invited me to give a talk at the Munk School of Public Policy and Global Affairs at University of Toronto in December. After that I’m off to Kyoto, Japan, to participate in a study group of professors, and to launch my next project.”

By Katie Neitz

By Katie Neitz