Prof. Markus Dubischar and his class encounter Greco-Roman architecture and icons on a New York City trip.

By Bryan Hay

By Bryan Hay

Markus Dubischar thrives on exploring classicism in the modern world.

He eagerly pulls volumes from his office bookcase that detail Greco-Roman architecture and iconography in early America, the antebellum period and into the 20th century.

In an instant, he’s drawn toward an image of a 12-ton neoclassical marble statue of George Washington wearing a chest-baring toga perched atop a granite pedestal, searching for its inner meaning. It was originally installed in the Capitol rotunda after Congress commissioned it in 1832.

“A rotunda is itself an architectural signifier for ancient Rome,” says Dubischar, who heads the classical civilization program. “It’s reminiscent of the Pantheon’s mega-rotunda and many smaller rotundas in palaces and public baths of Rome.”

Moreover, he says the Founding Fathers’ idea of the aristocratic, large-land-owner general who, after winning a war for his nation, releases the army and gives up his military might was also an important civic ideal of the Roman Republic, celebrated, for example, in the legendary patrician Cincinnatus.

“George Washington and his contemporaries knew these stories well and modeled themselves and their young country after them,” Dubischar notes.

“George Washington and his contemporaries knew these stories well and modeled themselves and their young country after them,” Dubischar notes.

In his quest to present classicism in contemporary contexts, the professor relentlessly pursues eternal themes with the muses, ancient philosophers, and Greco-Roman gods at his back.

Not surprising, then, that Dubischar took his exploration and his students to the next level with an excursion to New York City this semester.

The Big Apple drips with classical motifs, although most tourists and casual observers would easily miss them or fail to appreciate their significance.

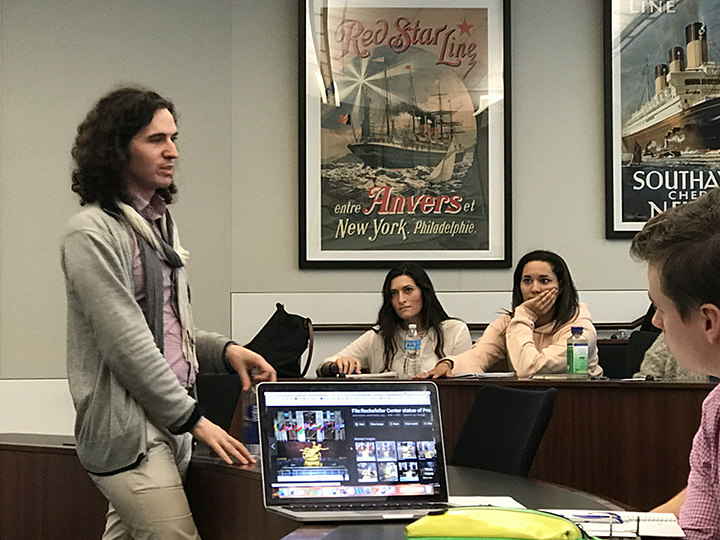

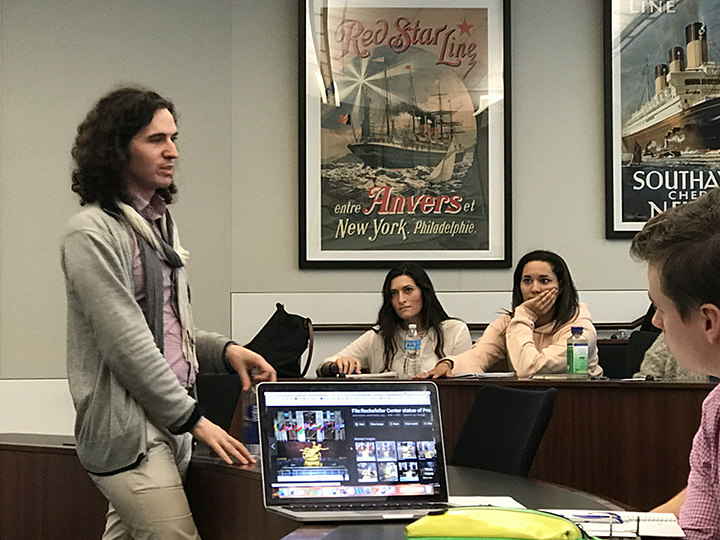

Rockefeller Center was among the stops where the group examined a cluster of mythologically themed architectural decorations and sculptures. Jared Simard, a postdoctoral fellow in classics at New York University who specializes in the reception of classical antiquity in New York City, particularly John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s deliberate use of ancient mythological motifs in public spaces, led the way.

“What impressed me the most was how much new material was here for me and my students to learn about Rockefeller Center,” Dubischar says. “There’s the iconic building, the statue of Atlas, the golden Prometheus, the representations of Hermes. I thought I knew what to expect, but the tour went so much deeper and beyond what I had anticipated I’d learn. For the students, it was triple that. It was eye-opening to see anew things at a site with which, I thought, I was already familiar.”

NYU fellow Jared Simard speaks to the class.

Rockefeller Center represents a significant moment in time. It was built during the Great Depression, yet its grandiose scale transcends a dour time and points toward modernism.

“Rockefeller Center combines breathtaking modern technology and architecture, but Rockefeller also wanted to connect it to humanistic ideals of classical antiquity,” Dubischar says. For Rockefeller, who oversaw the creation and placement of the artwork, the Greek and Roman imagery was not an academic exercise but a powerful statement about world peace.

“The international world was not stable in the 1930s, and Rockefeller believed that growing global commerce could be a way to avoid confrontation and prevent another world war,” he says. “In Rockefeller Center, we see Hermes, the god of commerce, and the thought behind that was that the world can become more peaceful through international trade.”

His students, too, experienced a classical awakening in a familiar place.

“I was surprised how much art there was in Rockefeller Center—relief sculptures, Greek figures symbolizing sounds and light on the main tower,” says John Jamieson ’18. “I’d been there before and saw Atlas and Prometheus, but I missed so much when walking through Rockefeller Center on my own.”

Simard’s explanation of Rockefeller’s rationale in choosing each piece brought clarity, he says, including how Hermes runs over water with the sun in the background in one relief, symbolizing business in the United Kingdom and alluding to the proud saying that “the sun never sets on the British Empire.”

Simard’s explanation of Rockefeller’s rationale in choosing each piece brought clarity, he says, including how Hermes runs over water with the sun in the background in one relief, symbolizing business in the United Kingdom and alluding to the proud saying that “the sun never sets on the British Empire.”

“I was most surprised with the amount of thought and symbolism that went into these pieces,” Jamieson says.

Tasnia Hassan ’18 was struck by the history of Rockefeller Center and the many mythological motifs depicting human nature and the progress of society.

“I was impressed with the choice of mythological references and drawn to the messages that John D. Rockefeller Jr. was trying to convey so that most Americans would understand them,” she says. “Atlas representing mankind’s advancement and how humans can rely on themselves for guidance, Prometheus a symbol of human hope. But there’s also a message that wisdom is not limited to just the divine, but is accessible to all.”

By Bryan Hay

By Bryan Hay “George Washington and his contemporaries knew these stories well and modeled themselves and their young country after them,” Dubischar notes.

“George Washington and his contemporaries knew these stories well and modeled themselves and their young country after them,” Dubischar notes.

Simard’s explanation of Rockefeller’s rationale in choosing each piece brought clarity, he says, including how Hermes runs over water with the sun in the background in one relief, symbolizing business in the United Kingdom and alluding to the proud saying that “the sun never sets on the British Empire.”

Simard’s explanation of Rockefeller’s rationale in choosing each piece brought clarity, he says, including how Hermes runs over water with the sun in the background in one relief, symbolizing business in the United Kingdom and alluding to the proud saying that “the sun never sets on the British Empire.”