More than 100 students across three courses presented their research at the 14th Annual Multidisciplinary Environmental Poster Session.

By Katie Neitz, Bryan Hay, and Stephen Wilson

It might seem like a night of numbers! 14 years. 3 courses. More than 100 students. 32 posters. Over 80 judges. But, as sometimes is the case, numbers can hide the deeper story … if you can catch it.

Art Kney, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering, is on the move. Standing on the second floor of Farinon, he presses a button on a megaphone and a horn bellows, sounding faintly like the long wooden alpine horn played in the Swiss Alps.

The sound signals to the judges that it is time to move. The 80 judges, nearly 60 of whom are from the greater Easton community, work in pairs and must score six posters.

Surrounding each poster is an interdisciplinary mix of students from three participating classes: Environmental Engineering and Science, Environmental Economics, and Introduction to the Environment.

“The event mimics a professional conference,” says James DeVault, professor of economics. “It combines the harder skills of creating and designing a poster and the softer skills of interacting with the public to present and defend that poster.”

DeVault has been working alongside Kney for the past four years and served as a judge for a number of years before that.

“The students learn what it means to be part of a team,” says DeVault. “They can’t just go sit in a corner office and do their own thinking. They must collaborate, pull their own weight, and get the project done.”

Why is this important? Most problems involve more than one disciplinary approach in order to create solutions.

“If you put three economists together, they all wear the same disciplinary blinders, seeing the world in the same way, and ultimately drawing the same conclusion around a problem,” says DeVault.

But three students from different disciplines in three different courses … and bam! Three different answers. All may have validity and viability.

“This gives students a chance to do research, synthesize material, butt heads, and engage in some complex thinking,” says DeVault.

Andrea Armstrong, assistant professor of environmental science and studies, agrees.

“Collaboration is the future of solving environmental problems,” says Armstrong. “Cutting-edge research on environmental solutions is happening in interdisciplinary teams and often in graduate school programs where disciplinary perspectives are being challenged and transformed. The poster session is preparing our students to take part in those conversations.”

Every year the topic of the poster session changes. In year 14, the topic is Climate Drivers and Ecosystem Change.

The winning poster was “Aedes Vector Migration in Arabia: Climate Change Causes Socioeconomic Peril” by Daisy Grace ’20, Jeremy Mintzer ’20, and Kevin Smith ’18.

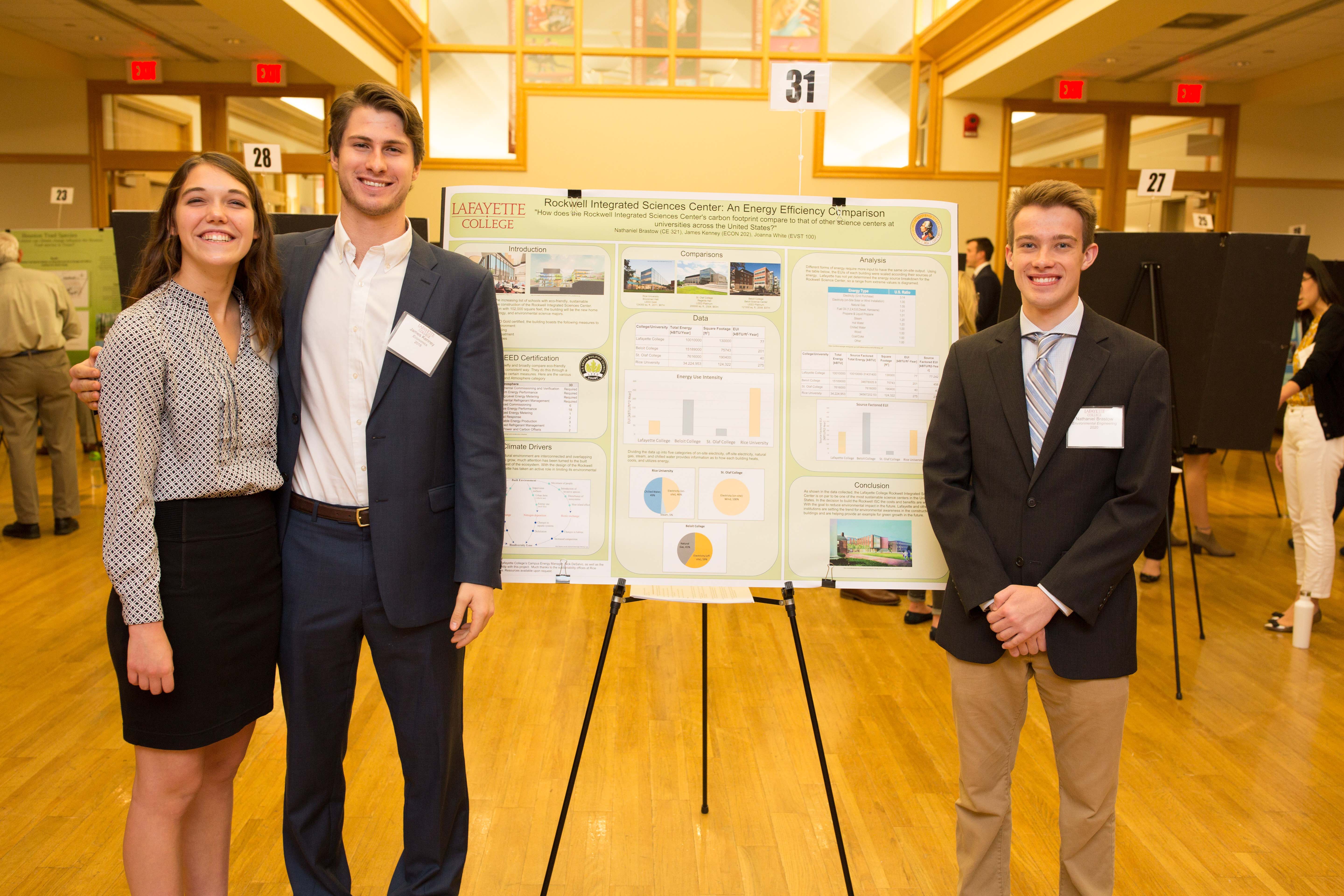

Second place went to “Rockwell Integrated Sciences Center: An Energy Efficiency Comparison” by Nathaniel Brastow ’20, James Kenney ’18, and Joanna White ’20.

Earning third place was “Seawalls as a Response to Rising Sea Levels in Miami Beach, Florida” by Eva Appelo ’21, Rebecca Cook ’20, Jack Gardner ’20, and Justin Morales ’18.

Recognized with honorable mention was “How Do Cities Adapt to Protect Wastewater Treatment Infrastructure Against Flooding in the Eastern United States?” by Ryan Antonelle ’20, Philip Brown ’20, Danielle Gardner ’20, and Ryan Moore ’18.

Here are some of the other posters from that night.

Stressed Out Cows = Less Milk

Rajhan Meriwether ’18 (economics), Shuli Eder ’20 (environmental engineering), Taylor Danson ’20 (environmental engineering), Chris Ambrosio ’20 (engineering studies)

Picture the beautiful central valley region of California, nestled between the Pacific coast and Sierra Nevada mountain range. The fertile farmlands. The grassy pastures. The stressed-out cows.

The Heat Is On

Extreme heat in the valley has increased from five days in 1950 to 28 days today.

What’s in a Hot Cow?

Bovines prefer temperatures ranging from 25 degrees Fahrenheit to 70 degrees. Extreme heat leads to heat stress in cows. They eat less, produce fewer nutrient-dense solids in their milk, and pregnancy rates drop. When the mercury hits 100 degrees, milk production drops 20 percent.

Milk Economics

Heat stress in 2010 totaled $1.2 billion in lost milk production. Think of what that means to milk prices and other dairy products, like yogurt, cheese, ice cream. Add to it the cost to keep cows cool. Fans, misters, and shading aren’t cheap.

Dairy Conclusions

The average temperature in the valley is up 3 degrees. Think what another increase will mean to your dairy. Talk about sour cream!

Flooding to Easton

Jake Levy ’18 (environmental engineering), Olivia Cubbage ’21 (environmental studies), Lauren Mathisen ’18 (economics), Jack Purdy ’18 (economics)

Longtime locals remember the big flood of 1955. But are they ready for the storm clouds on the horizon?

Rain, Rain Going Up

Since 1958, the northeastern portion of the U.S. has seen a 71 percent increase in precipitation.

Flood Numbers Rising

If 1955 was a big one, then the recent series just kept citizens and city officials on their toes: 1996, 2004, 2005, 2006, and 2011.

Ready for Rain

While Easton has made improvements to systems, it seems more education and preparation are needed in order to adapt to a changing climate. So the community is ready.

Wading Conclusion

Don’t buy a kayak just yet, but think about green roofs, levees, and more wetlands. And tell your neighbors.

Don’t “Pack” the Skis

Kelly Price ’20 (civil engineering), Aaron Wolfe ’18 (economics), Addie King ’21 (environmental studies)

Want to hit the moguls? In the future that term might have nothing to do with skiing and more to do with the Occupy Wall Street movement organized by the 99 percent.

Where’d the Snow Go?

With temperatures up, less snowfall, increased snow melt, and irregular snow events, the alpine economy is suffering because there is so little snow pack.

Fake It ’Til You Make It

Ski resorts are making more snow. But that process harms the alpine ecosystem. Making snow uses groundwater resources. Piping groundwater up a mountain disrupts soil layers. Artificial snow lasts longer, which delays plant growth. When it finally melts, there are added contaminants.

Costs of Snow

A few resorts have spent millions, ranging from $2 to $4.5 million, to increase snow. But for artificial snow to be effective, there must be cold—three days at or below 32 degrees. So resorts innovate to attract guests with alpine coasters, ziplines, rafting, and biking … at more expense. That expense gets passed onto consumers.

Snow Trip

Best bet? Head further north where seasonal temperatures are colder, the skiing season lasts longer, and the moguls are bigger. Hit them hard!

Green Roofs Save NYC

Emily Rabens ’20 (environmental engineering), Cynthia Mikula ’21 (environmental studies), Sian Barry ’18 (economics)

Creature comforts in cities as big as New York can have big impact.

Urban Heat

Not the name of a dance club, urban heat is the term for the increased temperatures in an urban landscape. NYC has seen a steady incline in temperature, increasing 2.4 degrees since 1970.

A Few Degrees Don’t Matter

Au contraire! Hotter days mean more air conditioners, taxing the demand for electrical energy and adding more pollutants to the air. Rainfall that might cool off a city has nowhere to go in an asphalt jungle, so it is retained as surface water. Those surfaces heat it more and increase the water temperature of runoff entering waterways.

AC Enemy

For every degree the temperature goes up above 68, city residents use 3,300 more megawatts of electricity.

Solution: Green Roof

Direct savings if 50 percent of roofs in NYC were green: $149 million. And temperatures would decrease over a degree. At a cost of $25-$50 per square foot, a green roof seems like the perfect place to catch a cool view of NYC.

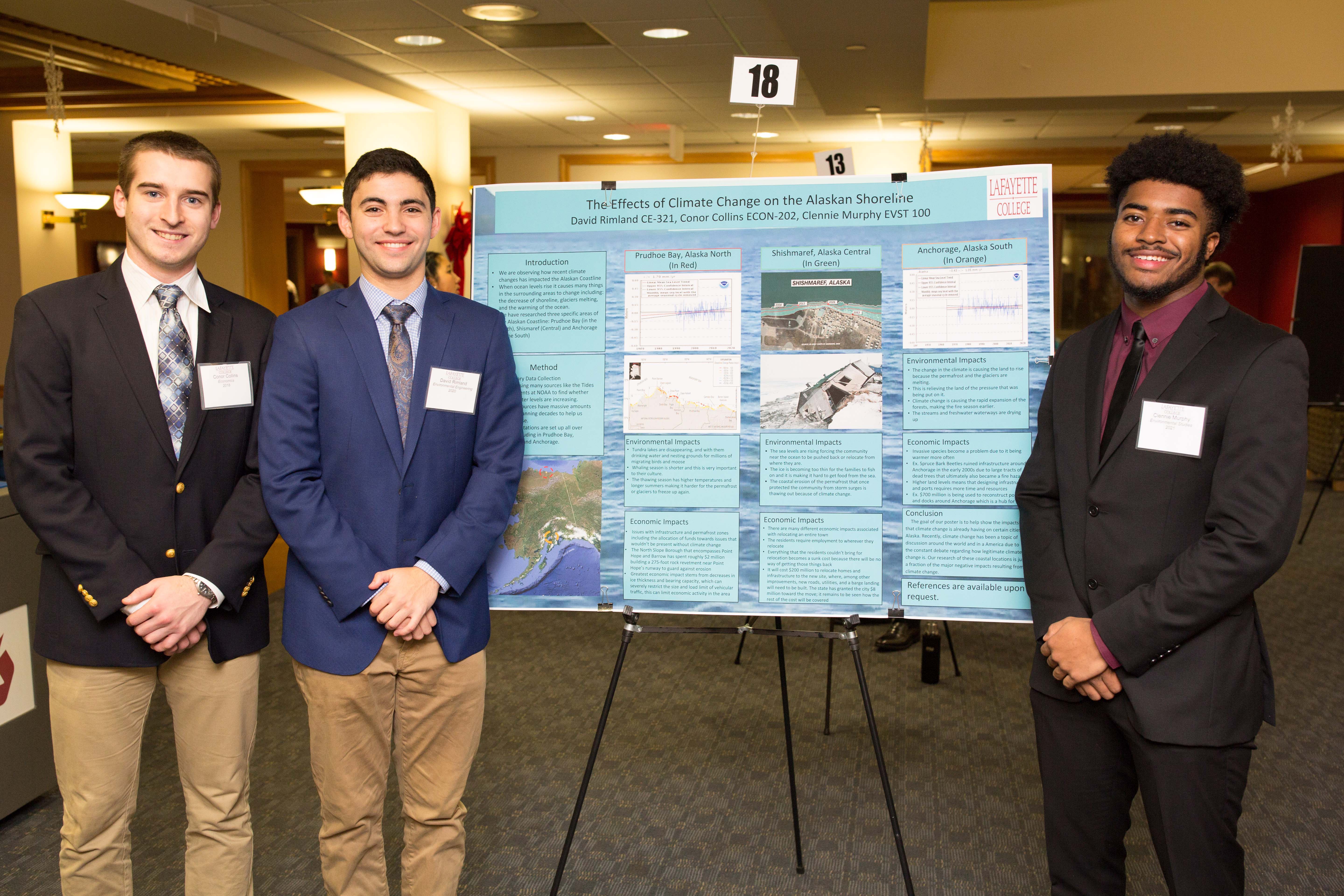

A Tale of Three Cities

Conor Collins ’18 (economics), David Rimland ’20 (environmental engineering), Clennie Murphy ’21 (environmental studies)

Things sure are heating up in Alaska. Temperatures across the U.S.’s largest state, which has land on both sides of the Arctic Circle, have increased approximately 3 degrees F, a rate that is twice that of the rest of the country.

Location, Location, Location

Climate change has impacted three specific areas of the Alaskan coastline: Prudhoe Bay (northern), Shishmaref (central), and Anchorage (southern).

Desperate Measures

In the small village of Shishmaref, sea levels rose so dramatically, the whole town is in the process of relocating to a new spot 5 miles inland. Talk about an upheaval: It will cost an estimated $200 million to move everyone and everything. New roads, new utilities, new homes.

Land of the Rising … Land?

Everyone’s always talking about rising sea levels, but in Anchorage, it’s actually the land that’s rising. As glaciers melt, they don’t just release water: Rocks, sand, and dirt that were also frozen within the glaciers flow. It’s harming the ports of the city, causing them to rust and crumble. And that puts the city’s economy in jeopardy, as Anchorage relies on marine vessels for imports.

Building a Wall

Oil wells and gas pipelines housed in the northern village of Prudhoe Bay are at risk from the dramatic erosion of Alaskan shorelines. The town is building a massive (and expensive) rock wall in an attempt to protect its land and this infrastructure.

Into the Sea

Animals and humans are adapting by moving, but relocation isn’t easy. And there’s no guarantee the new sites where people are putting a stake in the ground won’t experience future erosion. Gathering more research could help scientists and state and city officials manage their resources to safeguard their land.

Go Dutch to Engineer Around Storm Surges

Justin Soto ’20 (civil engineering), Robert Cuyjet ’19 (economics), Jesse Orellana ’20 (electrical and computer engineering)

Survival around flooded, gradually sinking land has always been a way of life for the Dutch.

Economics of a Waterlogged Nation

$450 billion in GDP a year is spent to protect the Netherlands, much of which sits below sea level, from flooding and storm surges.

Hard Solutions

Repeated floods led to the Maeslantkering in the late 1990s, a massive, moveable sea gate designed to protect against storm surges coming off the North Sea. Low-lying areas face more flooding with rising sea levels resulting from climate change; billions will be spent over the next century to extend the Dutch coastline and build more storm-surge barriers.

Soft Solutions

The Netherlands is also moving large volumes of sand to counter the lack of sediment deposition caused by hard engineering solutions. Wetlands are a first line of defense by absorbing water and slowing down storm surges and reducing flooding.

Dutch Solutions at Home?

The Dutch lowlands are similar to areas of the Gulf Coast, which is losing wetlands from development. Recent catastrophic floods are a preview of the danger that many low-lying areas in the United States may face if soft engineering strategies are not considered.

Somewhere Between Hard and Soft

Both hard and soft approaches need to be weighed as sea levels rise with climate change, and solutions should consider environmental effects and efficient cost distribution.

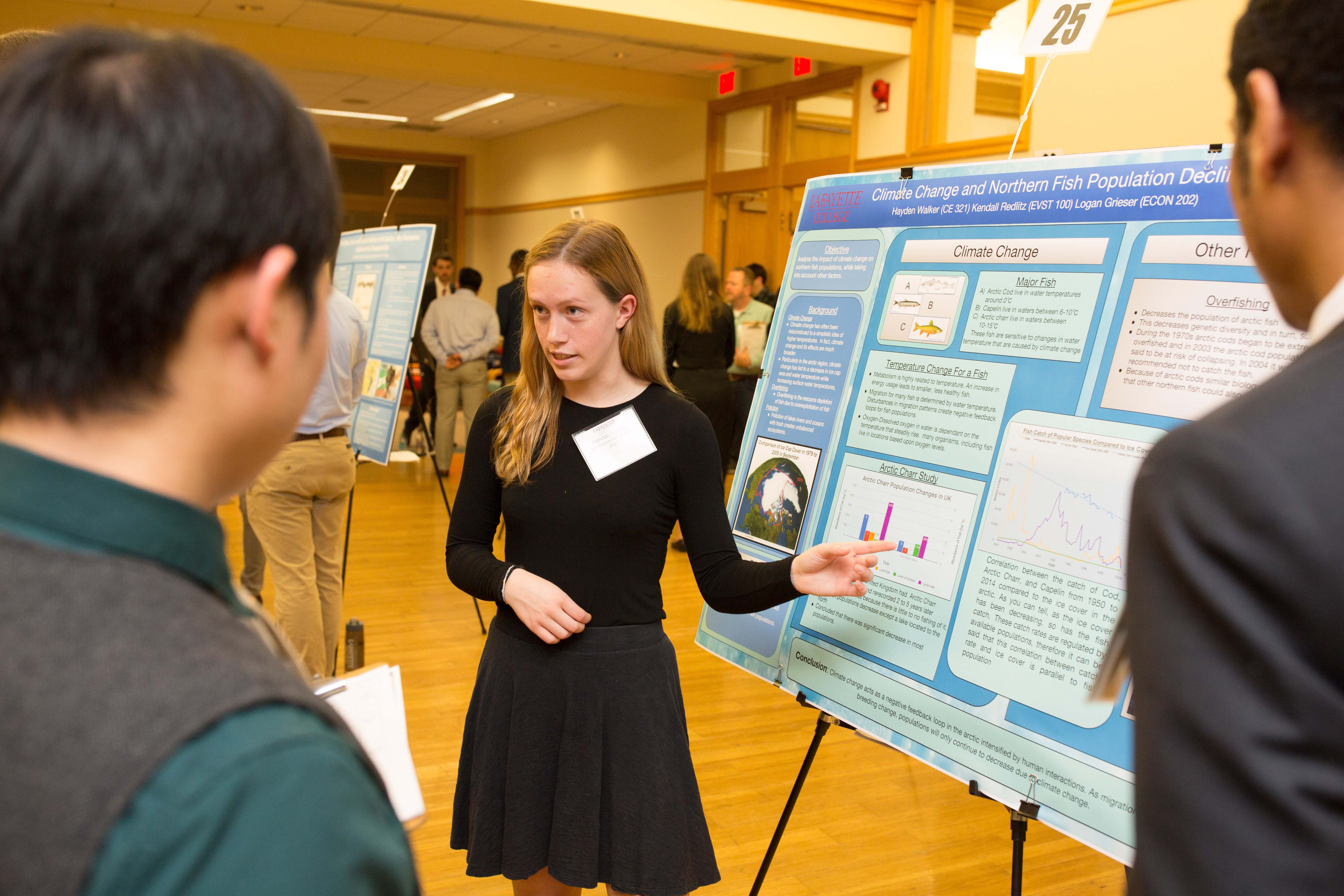

In Hot Water

Kendall Redlitz ’21 (environmental studies), Hayden Walker ’20 (civil engineering), Logan Grieser ’19 (economics)

Fish: It’s what’s for dinner in the Arctic. If fish are impacted by climate change, so will other animals up the food chain.

Warming Trend

The Arctic is warming at a faster and stronger rate than anywhere else on the globe. Which means northern fish could go belly up. Why? They thrive in cold water and are highly sensitive to changes in temperature.

Go Fish

Studies show a link between melting Arctic ice—caused by warming temperatures–and the catch rates of Arctic cod, capelin, and charr. Water temperature affects things like metabolism, feeding habits, migration, and mating seasons, and it can create a negative feedback loop … Which means if they mate too soon, they can create offspring that could be smaller and less healthy.

Deserted Waters

Another concern is that some fish might migrate further north to seek out cooler waters, and that could create barren areas. Northern fishing towns that rely on fish as an economic resource also could be vulnerable if water temperature changes lead to the decline in fish populations; fishermen lose work and communities will lose a food source.

Save the Fish!

At this point, reversing rising ocean temperatures doesn’t seem likely. Overfishing compounds the problem, and so as fish stocks move north, it will be all the more important to manage and protect them.

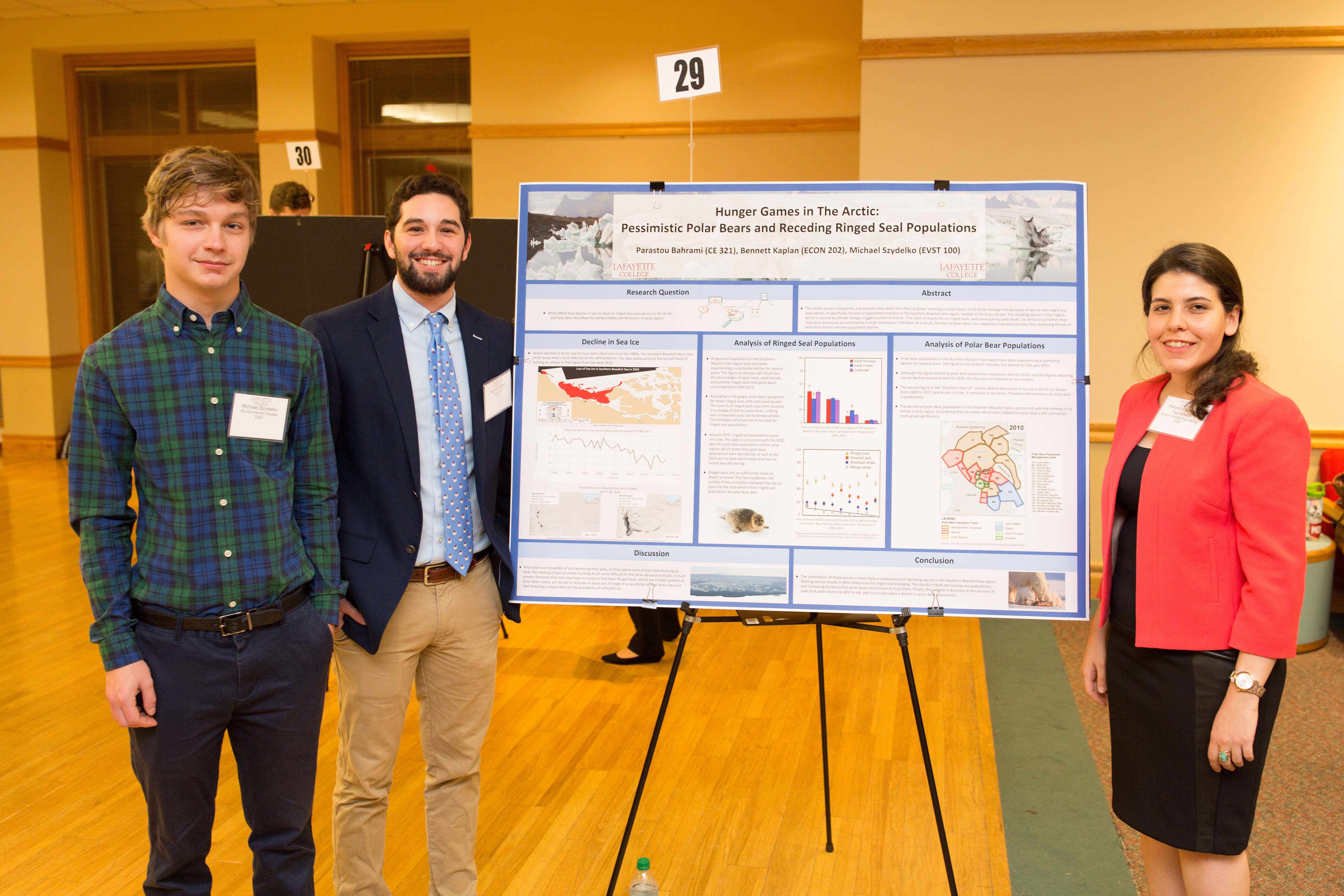

Polar Bears Are Getting Hangry

Michael Szydelko ’20 (environmental studies), Bennett Kaplan ’19 (economics), Parastou Bahrami Taghanaki ’20 (civil and environmental engineering)

Polar bears’ stomachs are growling. Warming temperatures are melting Arctic ice, which makes it harder for polar bears to get their fill of nourishing seal blubber.

Liquefying Assets

Ice in the Arctic Ocean’s Southern Beaufort Sea has been on the decline since the 1980s. As that thaw has occurred, ringed seal and polar bear populations have taken a hit. Thawing ice puts both animals in jeopardy: Seals rely on large, stable sheets of ice for breeding; polar bears use them as hunting platforms to catch dinner (seals).

A Double Whammy

Fewer seal pups + fewer hunting platforms = hungry polar bears. As a result, polar bears are traveling great distances to secure dinner and are resorting to land-based foods, which may not be as satiating and could impact other animal populations.

Sound the Alarm

The decline in sea ice is staggering. Photos taken just 20 days apart show a dramatic reduction in sea ice. 20 days! That alone might jog people to make different decisions and draw different conclusions about climate change.

Effects of Rising Temperatures on Malaria Endemic

Rebecca Blocker ’20 (civil engineering), Emily Keller-Coffey ’18 (environmental studies), Jake Weitzner ’21 (environmental studies)

Rising temperatures mean more hospitable habitat for disease-laden mosquitos. Malaria is most prevalent in sub-Africa and kills 400,000 people a year.

Mosquitos, So Sensitive

Temperatures can affect chances of mosquito survival, the incubation period of the malaria parasite inside mosquitos, and the length of time for female mosquitos to develop eggs.

Spreading across Africa

Africa is expected to warm by more than 3 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, a rate disproportionately greater than the global average, creating favorable conditions for the spread of malaria into areas of Africa not currently affected.

Buggy Economics

Economic prosperity would be impacted by a spread of malaria, factoring in the increased costs of medical care, absenteeism at school and work, and a drop in investments and tourism.

Protection Needed

Climate change will improve conditions for mosquito-borne disease across Africa; a coordinated response is needed now to protect vulnerable populations.

Rockwell Integrated Sciences Center—A Sustainable Trendsetter

Joanna White ’20 (chemical engineering), James Kenney ’18 (economics), Nathaniel Brastow ’20 (environmental engineering)

The $75 million Rockwell Integrated Sciences Center (RISC) is setting the pace among the nation’s collegiate science centers to raise the bar for environmental awareness.

LEEDing the way

RISC is poised to be gold-certified in the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program, with an innovative design to reduce energy consumption by 45 percent below the LEED baseline. The 103,000-square-foot building will be equipped with natural heating and cooling, stormwater treatment, and natural ventilation systems.

Not All Energy Sources Are Equal

Looking at similar science centers at Rice University and Beloit and St. Olaf colleges, the study considered the energy sources—off-site electricity, on-site solar, natural gas, propane, steam—and the dimensions and energy-use intensity of each building.

Raising the Bar

RISC will be among the country’s most innovative and energy-efficient collegiate science centers when it opens in 2019, on par with St. Olaf’s Regents Hall and better than Rice’s Brockman Hall.

Judges’ Thoughts

From Lauren Forster, environmental education specialist supervisor with Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Bureau of State Parks:

“I think the poster session is a great way for the students to get practice with communicating science and research. I appreciate getting to hear what the students are working on, and the poster session helps me to stay informed of current projects and research around the world. One of the presentations, ‘Effective Implementation of Emission Reducing Policies in Colleges,’ was pertinent to my work in helping to promote sustainability in primary and secondary schools. The group found that if an institution had set goals, a plan in place to accomplish them, and a method for reporting their results, they were more successful at reducing energy use. The importance of planning how to follow through on a stated commitment to energy reduction will be something that I communicate to teachers and administrators during an upcoming Green Schools workshop. There were other topics that I found interesting because they were new to me. I wasn’t aware that desertification was such an issue in China. I also learned about some new technologies in hydropower.”

From Ian Kindle, environmental education regional program coordinator with Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources:

“It was great to see all the hard work the students put into analyzing an issue and presenting what they learned. The event for me is a fun opportunity to meet a lot of students, see the work they’ve been doing, and give some constructive feedback about their scientific research and communication skills. One poster that stood out for being pertinent to my home and work was a study of flooding in Easton and the city’s response to this issue. The students did a good job portraying the magnitude of the issue for downtown and the local response, including municipal regulations and educational efforts by groups such as Nurture Nature Center, as well as recommending more actions that could be taken to offset flooding impacts. As a member of Easton’s Environmental Advisory Council and local resident, it was good to see students taking an interest in and studying issues that so directly impact the community where they’re going to school and contributing to the local conversation about real-world issues. I had just come from our monthly EAC meeting where we were contributing input to the city’s rewrite of its hazard mitigation plan, so I had just been thinking of many of the topics addressed by the students. In addition to the hyper-local, it was also great to see a cross section of climate-driven issues nation and worldwide and get a sense for what the students thought and learned about these issues.”