By Stephen Wilson

Sitting below the main roadside along Little Bushkill Creek near Newhart Park in Stockertown, Pa., is an old mill. The three-story limestone structure looks like it’s been lifted from a Camille Pissarro depiction of the French countryside with its slanted outbuildings, stacked cord wood, and greenery.

Inside, plank walls follow suit with longhand script marking grain orders from as far back as 1794. The Le Fevre family is said to have built and operated the mill. Despite the French name, Le Fevre’s notes on the wall are written in German, common for local Huguenot families. Le Fevre originally came to the area to work as a mason for German-speaking local Moravians.

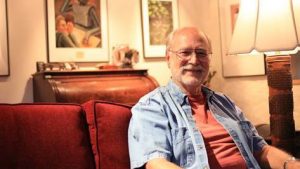

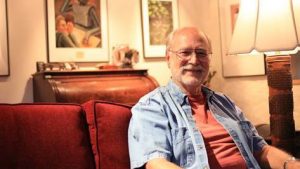

Much like the owners centuries before him, current resident Dan Bauer is a blend of artist and entrepreneur, anthropologist and STEM pioneer, scholar and mechanic, a regular jack-of-all-trades.

Founder of the Technology Clinic, Bauer is professor emeritus of anthropology at Lafayette. But he descends from a family of artists. His mother was a painter while his father was a gasoline engineer by day and a painter and sculptor by night. Their work decorates his home: nude torsos, head busts, scenic landscapes, abstract portraits, and self-portraits. His brother’s paintings fill the walls as do his spouse’s.

Founder of the Technology Clinic, Bauer is professor emeritus of anthropology at Lafayette. But he descends from a family of artists. His mother was a painter while his father was a gasoline engineer by day and a painter and sculptor by night. Their work decorates his home: nude torsos, head busts, scenic landscapes, abstract portraits, and self-portraits. His brother’s paintings fill the walls as do his spouse’s.

Several walls are covered in photographs Bauer took in Bhutan and other faroff locales. While he started off as a mechanical engineering major, his undergraduate degree was in photojournalism. He earned enough credits to have a second major in social science.

“I dabbled and dawdled long enough in my bachelor’s degree that it was taking longer than four years, and the Army was breathing down my neck,” Bauer says. The Vietnam War was in full swing. Rather than getting drafted, he left school two courses shy of his degree and signed up for the Peace Corps.

He landed in Chucuito, Peru, a city on the western side of Lake Titicaca. For two years, Bauer served the community in various capacities.

“I was an auto mechanic instructor,” he says. “I then installed pumps in wells, began a weaving cooperative, and grew potatoes.” These projects blended practical thinking, social justice, and experimentation.

“It’s easy to be an outsider and act like an expert with a cool idea,” he says. “But I learned instead to listen to the local people, knowing their wisdom and knowledge often held secrets that worked.”

Case in point with the spuds. He planted 36 potato plots, each using different seeds, plant spacing, tilling methods, and fertilizer. But if he hadn’t listened to the indigenous farmers, all his plants would have perished during the first cold breeze. By harvest, he’d helped farmers adopt some new approaches that produced better yields.

Inspired by his work in the Peace Corps, he took a year to complete the two classes that would wrap up his undergraduate degree. Why so long?

“The Peace Corps was my first sense of the value of anthropology,” Bauer says.

So he filled his schedule with anthropology courses and followed graduation with two years of fieldwork in rural Ethiopia studying household economics and politics in a village of 1,000 inhabitants. It set the stage for the Ph.D. he earned in anthropology from University of Rochester. Bauer began teaching at Lafayette in 1972.

In the mid-1980s, a new liberal arts approach was gaining traction that added technology to practical study courses.

“I had read a book called Synectics, which provided an operational way to add creative problem-solving to academic work,” Bauer says. “It helped me to see the world differently, but it wasn’t a perfect match with my ethnographic methods.”

Bauer sought a new application, one that was more interdisciplinary than he had seen at other institutions. The Sloane Foundation invited a select group of colleges to apply for a grant. He and a small group wrote a grant that was one of six funded nationwide.

That grant launched a number of curricular changes at Lafayette, including the Tech Clinic. Now in its 30th year, the Tech Clinic was the perfect place for all of Bauer’s trades.

“I could find clients, select top students from across disciplines, and have them view problems from various angles to help find solutions,” he says. He recruited a civil engineering professor, Vince Viscomi, and then got to work.

The first client was Safe Harbor Power Company. The business was struggling with the amount of debris floating in the Susquehanna River that eventually made its way to the Chesapeake Bay.

“There would be an acre of garbage floating in the bay that the company wanted removed,” Bauer says. “It was a problem the company had tried to solve with other solutions … exactly the kind of problem I wanted.”

Using methods from Synectics, Bauer, Viscomi, economics professor Jerry Heavey, and five students contemplated the river as an anthropomorphic entity and imagined solutions that would help it with a garbage issue.

They thought of filters, grinders, and digesters. Finally, they moved to another Synectic method and developed the concept for a mechanical version of a giant water bug that could collect the trash. While the first two models worked but had shortcomings, the third version of their bug became a model used across the globe.

With that first project done, the next 60 Bauer has worked on have run the gamut. Tech teams built drunk-driving simulators, models for large-scale vaccination campaigns, and a process to reduce landfill waste. Together, student and faculty teams have made physical products and generated massive thesis-style reports.

All hit the mark.

Upon Bauer’s retirement as a full-time faculty member, Lawrence Malinconico, professor of geology, took over leadership of the program. Bauer continues to work on projects. This year he and Malinconico are working with a regional health system to better track and measure the wellness of walkers.

“We have helped many clients solve problems,” Bauer says. “But the true impact is far beyond the solution.”

First, the Tech Clinic became a model on campus for how students and classes could approach their work and solve real-world issues.

More than that, students ignited passions using what they learned to start entrepreneurial careers, become leaders in their fields, or look for innovative solutions to problems. Bauer can rattle off student names, projects, and career trajectories.

Finally, Bauer altered his path. “It changed how I studied anthropology,” he says. “As a social anthropologist, I paid attention to the social and political aspects before me and did not pay enough attention to the economic, ecological, and technological aspects. No longer could I ignore some aspects that surround a culture, knowing all members of a community are actors in very complex systems.”

The Tech Clinic gave him a reason to try new things.

“I have been studying my own brain chemistry—what causes my norepinephrine or dopamine to spike while doing certain activities and how it relates to my own DNA,” he says. He looks around at the bathroom he built, rafters he cut, digital darkroom he runs, tile he laid, 3-D printer he operates, cars he rebuilt … all projects that fill and surround his old mill.

“Life in the Tech Clinic has helped me to dig deeper, learn how to do things, understand the anatomy of an issue,” Bauer says. “I’ve been able to understand what’s not articulated in a problem and bring an outsider’s perspective as I get inside that issue.”

He soon flies out to Peru. He is visiting for the first time since his Peace Corps service. Crafting a lecture in Spanish, he will speak with villagers and Peace Corps alumni about how outside thinking and insider knowledge can transform people and places and at the same time feed the soul.

They have the potatoes to prove it.

Founder of the Technology Clinic, Bauer is professor emeritus of anthropology at Lafayette. But he descends from a family of artists. His mother was a painter while his father was a gasoline engineer by day and a painter and sculptor by night. Their work decorates his home: nude torsos, head busts, scenic landscapes, abstract portraits, and self-portraits. His brother’s paintings fill the walls as do his spouse’s.

Founder of the Technology Clinic, Bauer is professor emeritus of anthropology at Lafayette. But he descends from a family of artists. His mother was a painter while his father was a gasoline engineer by day and a painter and sculptor by night. Their work decorates his home: nude torsos, head busts, scenic landscapes, abstract portraits, and self-portraits. His brother’s paintings fill the walls as do his spouse’s.

1 Comment

I have known Dan for about 25 years. We both have MG TC sports cars. Fortunately for me Dan knows all there is to know about cars. He has rescued me many times on car issues. We enjoy going to car shows together where we share stories with other car people. It is a real treat to hear his stories about growing up in California, projects he is working on at Lafayette and the time he spent in The Peace Corps. To quote the TV beer

commercial, “He is the most interesting Man in the world”

Comments are closed.