By Bryan Hay

“If it tastes like butter, but it’s not …”

Since the rise of processed foods in the 19th century, Americans have been on the lookout for those who dare to fool Mother Nature, maintaining a healthy skepticism of the source and quality of their food, a movement that ultimately led to the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906.

In his forthcoming book, Pure Adulteration, under contract with University of Chicago Press, Benjamin Cohen, associate professor of engineering studies, is exploring the environmental and cultural history of the pure food crusades and how Americans struggled with perceptions of pure versus adulterated food.

“People in the second half of the 19th century were fascinated with how the concept of pure and natural changed with the rise of manufactured food,” Cohen says. “There was growing concern about what food people were consuming.”

At one time, consumers shopped for food by placing their order with a grocer who disappeared behind a curtain to retrieve the requested food items, much like a pharmacist working behind a counter.

“Grocers were often accused of adulterating food from behind the counter,” Cohen says. “They were caught up in a long lineage of social commentary about whether someone was the genuine article or a fake. It came to a head with mobilized populations, immigration, urbanization, when people didn’t feel that they knew who they were dealing with. Frauds proliferated as a result.”

A cartoon detail from 1884 from the satirical magazine Puck

To show the zeal behind 19th-century food purity, Cohen points out an 1887 satirical cartoon in Rural New-Yorker magazine. It shows a farmer, with industrialists looking on, fighting off a three-headed hydra whose necks are stamped with controversial adulterated foods and food additives of the day—cottonseed-oil, which was used as a cheap filler in olive oil and shortening, glucose, which at the time was a term for fake sugar, and oleomargarine. The hydra’s main trunk bears the word “fraud.”

In the age of P.T. Barnum, con men surfaced in the confusion over natural and artificial food.

One of the most successful was chevalier Alfred Paraf, a French chemist and well-groomed playboy with a waxed mustache who stole the patent for margarine, established margarine factories, and swindled people across the United States.

Consumers thought that margarine was born far from the farm, an aberration of natural butter, Cohen says. But in a time when population centers were shifting from rural to urban centers, consumers didn’t always catch on that the greasy stuff they smeared on bread was any different than natural butter.

As margarine, dyed to resemble butter, started to replace butter in restaurants, consumers stiffened their suspicions that grocers and food purveyors might somehow be selling something other than butter and demanded the real article.

Pro-butter lobbyists launched a marketing campaign aimed at convincing the public that if you think it’s butter, it’s probably not, and even tried, unsuccessfully, to mandate that margarine be colored pink to distinguish it from butter. Paraf was eventually jailed for his chicanery.

“Generally speaking, when you start to make food in factories, consumers don’t know what’s going on and begin to question if the ingredients are valid and genuine, or if the whole process of artificiality is offensive,” Cohen says.

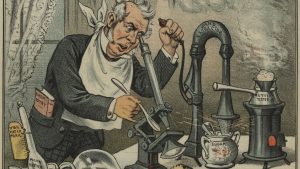

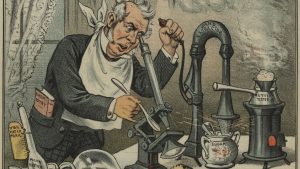

A cartoon detail from 1880, from the satirical magazine Puck

Some things haven’t changed since the 19th century, he adds, noting that Americans are studying food labels more than ever, questioning what’s in food and joining the farm-to-table movement as a way to rebuild connections that help them see their part in food production and sourcing.

“It’s still about artifice, nature, con men, and food,” Cohen says. “We’re asking the same questions—will it make me sick, am I being cheated, is this natural or adulterated food?”

Cohen puts his scholarly pursuits into practice by serving as a member of the LaFarm Advisory Board, an adviser to the Lafayette Food and Farm Cooperative, and along with geology professor and Tech Clinic mentor Larry Malinconico, one of the advisers for Vegetables in Community, a summer program that builds relationships with food between producers and consumers to help grow trust and confidence in food quality.

“These programs are a way to build a healthier environmental future by not assuming we know our food only through analytically certified labels, run through a scientific lab to make sure it’s what the producer said it was,” he says.

“Agricultural work takes a lot of scientific know-how too—conservation biology, soil science, agronomy, geology, and various food sciences, so my point isn’t that labs are bad,” Cohen adds. “Just that I’d rather know my food by understanding my connection to agricultural systems than from a lab test.”