Students learn about the geology of Iceland while exploring one of the most beautiful places on Earth

By Katie Neitz

Features that make Iceland a geologist’s paradise—volcanoes, glaciers, igneous rock—also make it a powerful learning environment. And so, in August, associate professor Lawrence Malinconico, associate professor Dave Sunderlin, and assistant professor Tamara Carley guided 24 students on an 18-day exploration of the land of fire and ice.

“One of our objectives is to provide students with the opportunity to see as many geological environments as possible,” Malinconico says. “We value being able to provide students with the opportunity to explore and then to understand the science behind processes, like volcanic eruptions, erosion, and glacial outbursts, and to also understand the impact those processes have on humankind.”

It was the department’s second Icelandic adventure, which was added to the its travel offerings in 2015. Geology professors also organize interim-session excursions to Hawaii, New Zealand, Ecuador, national parks of the southwest United States, and Wyoming to give students valuable hands-on fieldwork.

The experiences not only bring classroom lessons to life for geology majors, but they also enable professors to extend their reach beyond their typical audience. “Most of the students who traveled to Iceland were outside our major,” Malinconico says. “On almost all of our trips we’ll incorporate discussions on climate change and the global and local impacts, which are important for non-geologists and non-scientists to understand. Hearing about climate change is one thing, but being in an environment where you can see and measure the glacial retreat is another.”

Here’s a peek at their experience.

The class visits Fjallsárlón Iceberg Lagoon, a glacial lagoon in the shadow of Iceland’s tallest volcano, the Öræfajökull glacier. “We drive all around Iceland, and we punch into the interior,” Malinconico says. “That enables students to see things they typically wouldn’t see as tourists.”

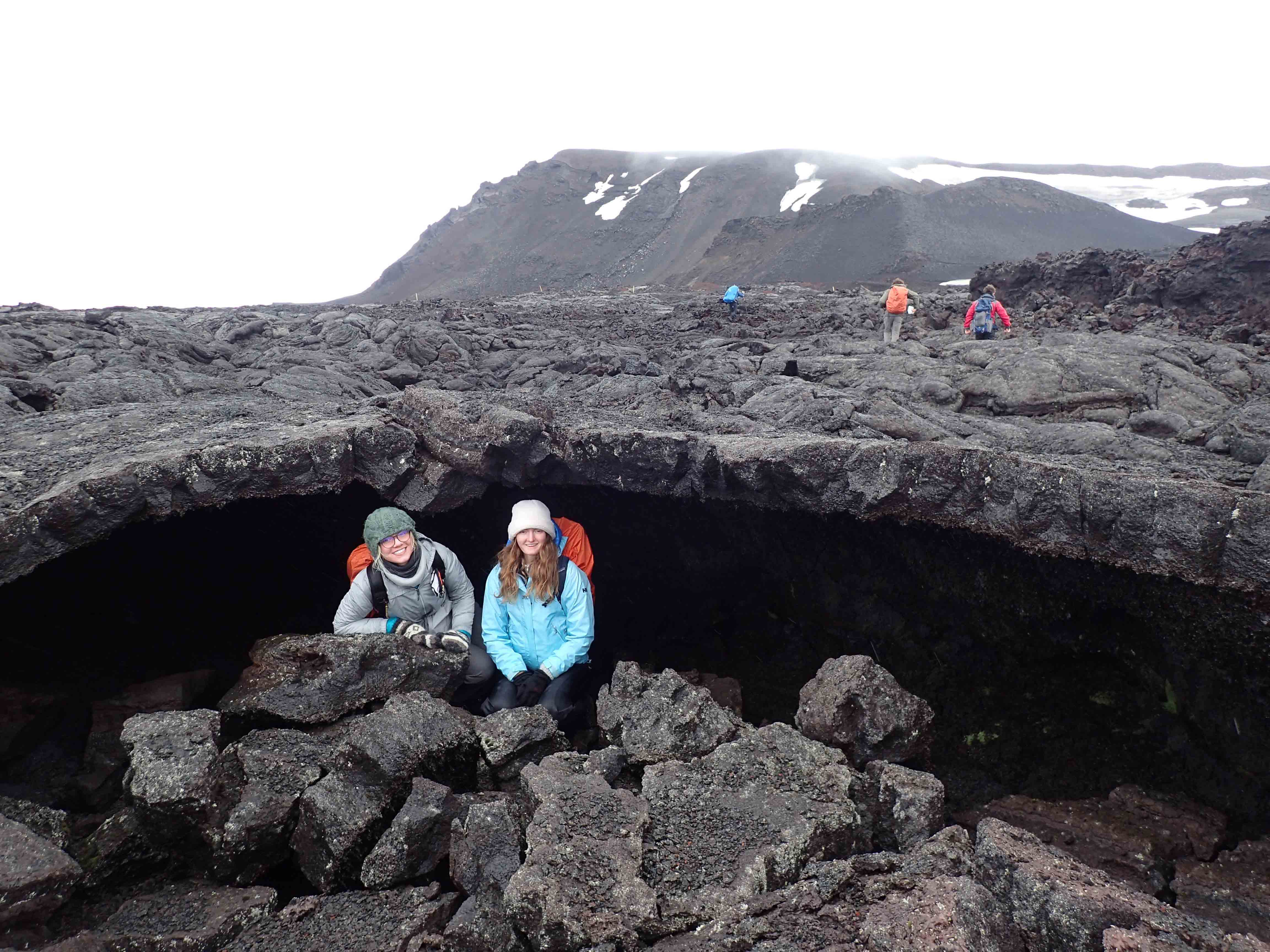

Students explore well-preserved pahoehoe flow features at the Vikrahraun lava flow, which erupted from the margin of the Askja Caldera. “The mountain in the background—Norðurfjöll—is composed of hyaloclastile—fragmented lava that erupted underneath thick ice caps during a glacier period,” Carley says. “Norðurfjöll defines the northern wall of the Aksja Caldera. Askja erupted explosively about 10,000 years ago and again in 1875.”

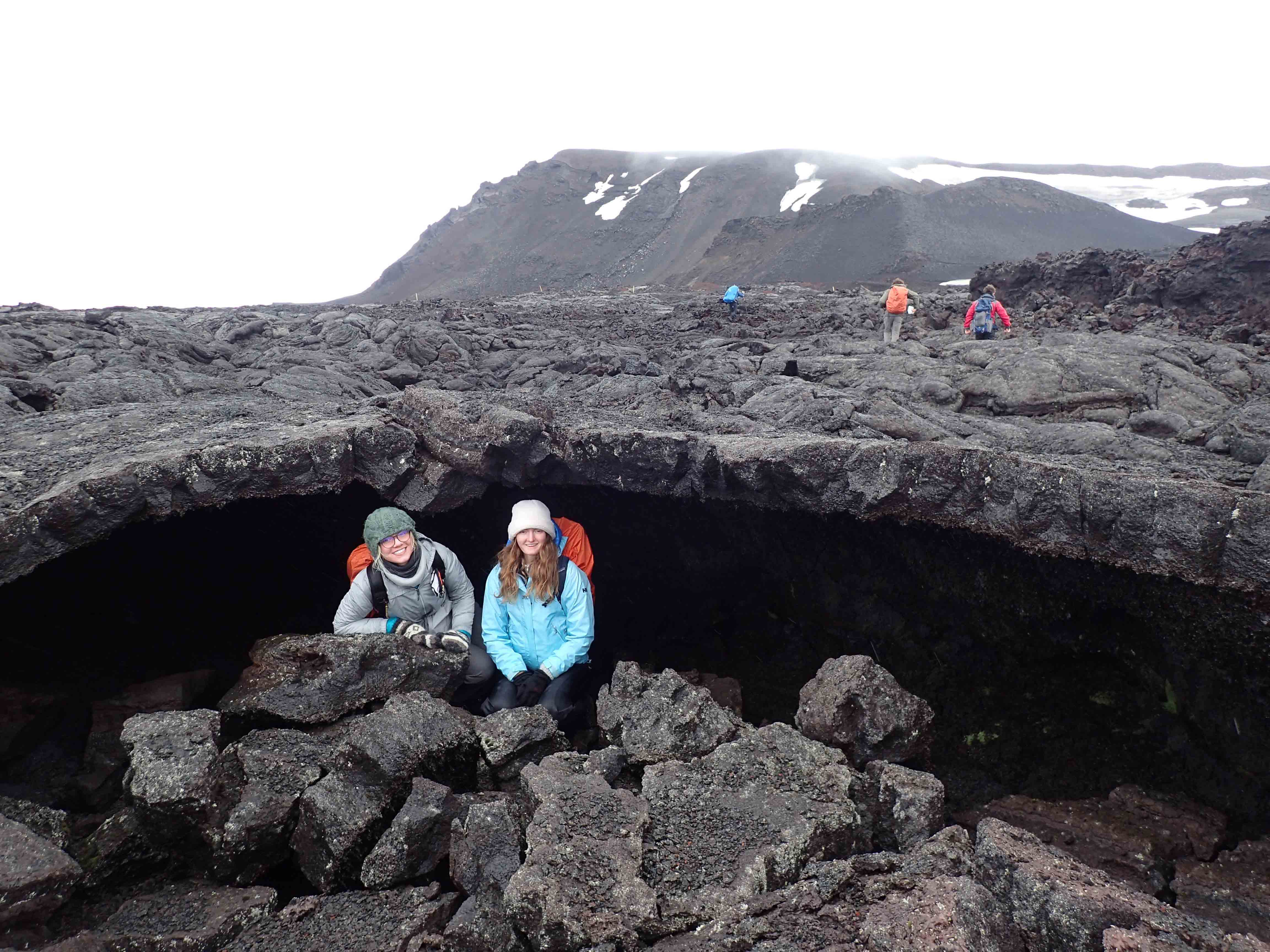

Cecelia Palmquist ’20 and Agata Benbenek ’20 in a “lava tube” at Askja Caldera. “Lava flows often roof over and form a lava tube,” Malinconico says. “It would’ve been filled with flowing lava. They are all over Iceland. You can go inside, and it feels like you are in a cave. If you go in really far and turn your flashlight off, you can’t see at all. It’s completely dark.”

“We stopped for a group photo while driving through the remote, rugged Icelandic interior to visit the Askja Caldera,” Carley says.

“This was a beautiful day for us,” Malinconico says. “We had clouds that came in, but to be able to see all of this was just spectacular. Because it’s so wet, the rocks get covered over incredibly rapidly with moss.”

Malinconico lectures at the base of Eystrahorn, a steep mountain comprised of loose rock, where precious minerals, including gold, silver, and mercury, have been found.

Simon Rybansky ’19 sketches against the backdrop of Eystrahorn. “One of the things that is important for students to learn to do is field sketching,” Malinconico says. “Geoscience is a very visual science. We encourage students to sketch what they see. It is much better reinforcement than just taking a photo and looking at the photo. You have to think about what you are sketching. Their field notebooks are an important learning tool.”

Sunderlin discusses dike intrusion near the fishing village of Djúpavogshreppur, which is located on a peninsula in southeastern Iceland. “Dikes are solidified intrusions of sub-surface magma that cut across the surrounding layered rocks,” he says. “In this case, the dikes cross-cut the amazingly thick sequence of lava flow after lava flow. We not only studied the features in front of our noses, but we also considered their orientation relative to the divergent spreading apart of Iceland. Our exercise there considered the details and the broad context of the features.”

Students visit Hvitserkur, a 49-foot-tall cliff that juts out of the Atlantic Ocean. “Hvitserkur is a remnant of a dike,” Sunderlin says. “Its planar orientation parallels the spreading direction of the Icelandic rift system. Erosion has made those ‘windows’ in it at water level.”

Carley leads a group discussion in which students identify geologic evidence preserved in the landscape and determine the sequence of events that created Kolugljúfur waterfall in northern Iceland.

Malinconico, Sunderlin, and Carley at Lakigigar, or Laki, a volcanic fissure in the south of Iceland. “That was a spectacular day,” Malinconico says. “You could see for 40 to 50 miles, which is just unusual. It is one of the largest eruptions in Iceland. We could see the lava fields, and we talked about the global impacts of the eruption.”

Students sit upon lava formations and columns that formed at Reynisfjara Black Sand Beach. “These are big lava flows that cool like this,” Malinconico says.

Rebecca Webster ’19, Paige Santelli ’19, and Kristen Ingraham ’19 are at the top of a steep climb at Thorsmork in southern Iceland. “Behind them is a dynamic braided stream—a high-energy river, fed by glacial meltwater,” Carley says. “This river frequently cuts and weaves and changes its course across the gravel braid plain that fills the valley. Glacially fed rivers in Iceland, such as this, can experience ‘jökulhlaups’ or glacial outburst floods, if trapped meltwater suddenly escapes from beneath the ice.”

Ingraham and Santelli hold a piece of ice from Jökulsárlón Glacier Lagoon. “That ice is from a glacier that could be 10,000 years old,” Malinconico says. “We went out on a boat in a big lake that formed from glacial retreat. There are smaller stranded icebergs that wash up on shore, and we were able to visit those, which was a really cool experience.”

“We visited a geothermal field on the Golden Circle, a famous Iceland tourism circuit close to Reykjavik, to see Geysir, the geyser after which all other geysers on Earth are named,” Carley says. “While Geysir itself no longer erupts, there are several hot pools and streams in this geothermal field. Students here are watching a geyser called Strokkur erupt water and steam. It happens approximately every 10 minutes.”