Students' digital project considers imprisonment and execution through human rights lens

By Stephen Wilson

Just after midnight Dec. 7, 1982, Charlie Brooks Jr. was the first man to be executed by lethal injection in the United States. While this landmark case is old news, impacts of the execution continue to reverberate, affecting many people, and their stories still deserve to be heard.

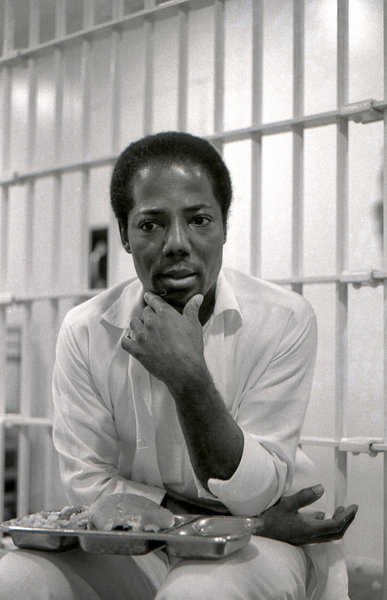

Charlie Brooks

In Prof. Andrew Uzendoski’s class titled Human Rights and Rhetoric, students listened.

Thanks to the work of the Texas After Violence Project, a restorative justice organization that partners with University of Texas at Austin’s Human Rights Documentation Initiative to make oral histories available online, students could listen to narratives by family members of Brooks, including sons Keith and Derrek. With an eye to the multi-generational effects of the death penalty, students considered the human rights of people convicted of serious crimes in addition to rights of crime victims and their families.

Students began by examining the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, a document created by a collective body.

“The committee charged with writing it included delegates from all over the world,” says Uzendoski, visiting assistant professor of English. “It’s important for students in an intensive writing course to see what collective writing looks like—how it bridges language barriers and various cultural contexts.”

To further that notion, the course content drew on various approaches to human rights storytelling, like the graphic novel Maus by Art Spiegelman that depicts his father’s experiences as a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor, the memoir A Long Way Gone by Ishmael Beah that describes his time spent as a child soldier during the civil war in Sierra Leone, and the film In the Name of the Father, based on the true story of four Irish citizens falsely accused of bombing a British pub.

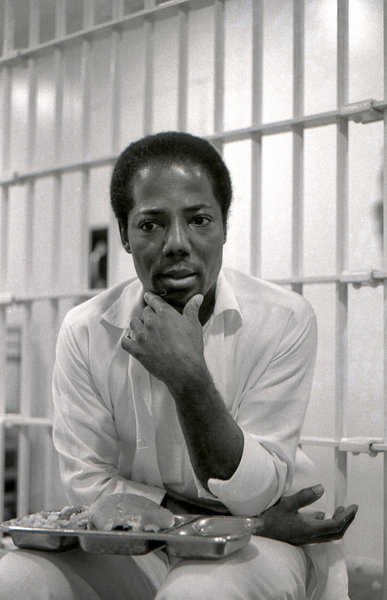

Derrek Brooks (far right, wearing cap) and friends on high school graduation day

The course concluded with a digital project considering the imprisonment and execution of Brooks through a human rights lens. For most Americans, Brooks’ story is one of headlines and brief news stories. But the history of his life and case are much richer and deeper.

While in prison, Brooks accepted accountability for his role in a crime, converted to Islam, served as a spiritual leader for other inmates, offered frequent support and guidance to his sons, and educated himself in law to become a trusted source of legal advice for others in prison.

Exploring materials surrounding Brooks’ case, students read, watched, and listened, considering oral histories alongside artifacts from the Brooks family collection in order to analyze the complexity of human rights issues.

“Students wrestled with ideas like Brooks’ accountability, the treatment of the guilty, the loss of rights, the application of justice, and the multi-generational impact of his death,” says Uzendoski. “By reading letters between Brooks and his sons, listening to Keith and Derrek’s oral histories, and hearing from officers who have played a role in executions, students could put this case into conversation with specific human rights principles.”

He didn’t want to push them to believe one way or another, but to see how skills taught in an English class, like narration and context, can help shape beliefs.

Charlotte Nunes, director of digital scholarship services, who led the digital project in the class, understands that history demands what she calls archival presence.

“The historical record is determined by what is captured, saved, and preserved,” she says. “The labor behind the scenes in archives can determine what perspectives are absent or present in historical narratives. This is the constructed nature of history.”

Nunes published a journal article on the topic in Oral History Review: “‘Connecting to the Ideologies That Surround Us’: Oral History Stewardship as an Entry Point to Critical Theory in the Undergraduate Classroom.” In it she talks about the power of engaging with community-generated oral histories for students to grasp principles of multiplicity, counter-narrative, self-reflexivity, and the contingent nature of history.

This topic was on clear display at the College as it hosted the Lehigh Valley Engaged Humanities Consortium (LVEHC) Oral History Workshop. Co-directed by Nunes and Andrea Smith, professor and head of anthropology and sociology, and supported by a four-year grant from Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, LVEHC fosters exploration of personal, historical, and community narratives that have emerged in the past half-century in the Lehigh Valley using methods of the humanities and arts. It offers a number of grants available to faculty, librarians, community members, and others interested in oral history as a way to contribute to an inclusive historical record. At the LVEHC oral history workshop that took place at Lafayette May 24, speakers from Lehigh and Muhlenberg discussed their insights from gathering local oral histories, like creating a record of dissent that is often excluded from the campus narrative or collecting stories of women who worked at Bethlehem Steel or the consolidation of South Bethlehem churches.

For students and other members of the Lafayette community engaging oral history, it’s a chance to contribute to the historical record and influence public discourse. And maybe, just maybe, understand the legacy of Charlie Brooks Jr. as more than what’s depicted in headlines.