By Bryan Hay

By Bryan Hay

More than a month after Lafayette’s participation in a statewide brownfields conference, the experience is still inspiring students and awakening an interest in redeveloping idle industrial sites.

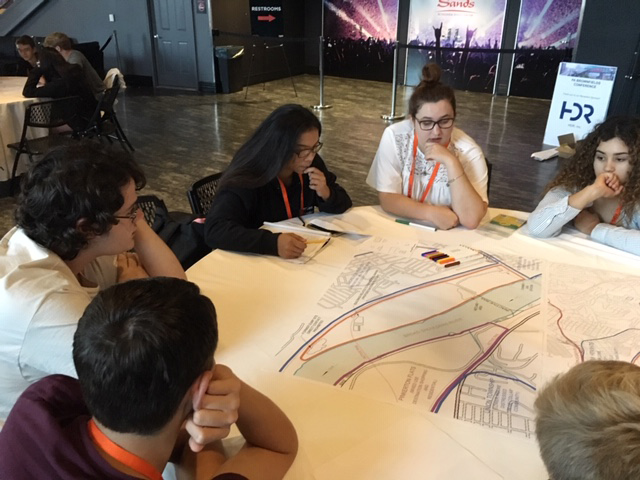

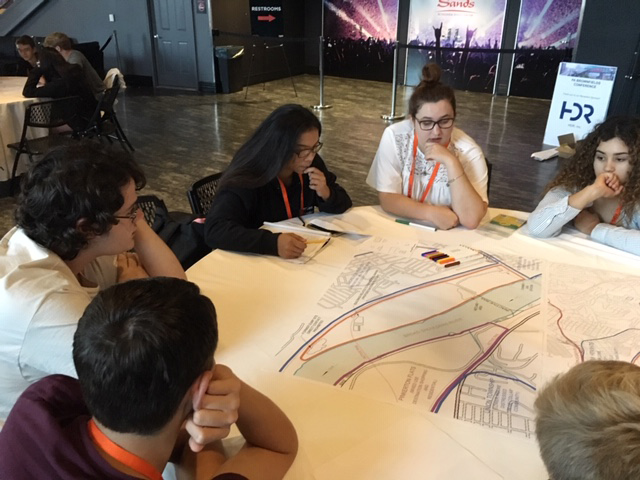

Typically geared for high school students, the educational sessions at this year’s PA Brownfields Conference involved three Lafayette civil engineering majors who worked collaboratively with the younger students alongside local and regional environmental and land use professionals in a three-day exploration of Pennsylvania’s brownfields program.

Students from seven Lehigh Valley high schools joined Cayden Godsey ’20, Kyle Low ’20, Vanessa Pagano ’19, Arthur Kney, professor of civil and environmental engineering, and 400 other attendees at the ArtsQuest Center at SteelStacks in Bethlehem, Pa. A popular destination for entertainment and festivals, SteelStacks campus provides a birds-eye view of historic Bethlehem Steel blast furnaces, the largest brownfield site in the United States.

For Godsey, the conference was particularly inspiring. Growing up in Marietta, Pa., an old pig iron furnace and silk mill town on the Susquehanna River, he understands how abandoned brownfield sites can be reborn as valued community assets.

“I grew up surrounded by old industrial sites left dormant that have been transformed,” he says. “I’ve seen them go from blighted, fenced areas into living areas. During the conference, we took a hypothetical site, similar to Marietta, and started from the ground up and asked ourselves ‘what can we do with this—how can we positively impact the communities that surround this site?’”

Godsey was so moved by what he learned at the conference that he arranged to shadow Vincent Carbone, a senior geologist for the engineering firm HDR who helped organize the conference. He enjoys the challenge of how to remediate and redevelop a brownfields site and make it last for generations.

“Getting rid of it and leveling it and starting over is not exactly the way to go,” he says, noting that younger people are moving into urban areas and looking for amenities with historical character, like the redeveloped Simon Silk Mill in Easton.

“Sites like that are attractive to younger generations,” Godsey says.

“Development of brownfield sites keeps the spirit of a community alive and builds local pride and helps create jobs,” Low says. He says he enjoyed spearheading conversations with the high school students about how to consider adding recreational facilities, boardwalks, and landscaping during the various exercises to reimagine the hypothetical brownfields site.

Pagano, who is taking Kney’s environmental site remediation course next semester, says the conference encouraged her to consider a field in brownfield redevelopment.

“Going to the conference made me want to take the course even more,” she says. “It’s work where you can immediately see the positive effect it will have on a community as well as the land. It’s not just something you do for the land; it’s something you do for the people who live there.”

For students like Godsey, Low, and Pagano, brownfields present many career opportunities.

“Some start with geology or engineering or landscape architecture,” Carbone says. “It matures from there—you start in one place, and suddenly there’s a path that you can take that’s up to you.”

Carbone also likes to remind students the world is becoming more miniaturized, whether it’s a two-megabyte hard drive that once fit in the back of a truck and now can be held in one hand or cavernous industrial buildings that no longer serve their original use.

“They’re not necessary anymore. With miniaturization, you don’t need all this room,” Carbone says. “So how do you make something that’s going to benefit the community from these sites? That’s what makes this so interesting.”

Among the goals of the conference was to expose students to the brownfields development industry and get them interested in it. Kney, director of Landis Center for Community Engagement, says that was achieved.

“I teach a class on environmental site assessment, and there are one or two students who end up with it as a career,” he says. “They don’t even know it as a career until they get in the class. Envisioning how a site goes from a fallow, environmentally impaired property to a vibrant gem of a community is not only a challenging intellectual exercise, but it can lead to an inspiring and rewarding career.”

By Bryan Hay

By Bryan Hay