Notice of Online Archive

This page is no longer being updated and remains online for informational and historical purposes only. The information is accurate as of the last page update.

For questions about page contents, contact the Communications Division .

Winter interim course teaches Earth's history in a natural laboratory

A course itinerary that includes hiking up Andean volcanoes with views of glaciers and snorkeling along the coast of the Galapagos Islands where Charles Darwin formed some of his ideas of evolutionary biology gives students quite an appreciation for the history of Earth.

As part of their biennial January interim course, “Geological and Paleobiological Evolution of Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands,” Lawrence Malinconico and David Sunderlin , associate professors of geology and environmental geosciences, used Ecuador as a natural laboratory. Twenty-four students from a variety of majors learned about the origin of oceanic crust and hotspot island archipelagos, the development of continental mountain ranges, and the relationship of geological processes to biogeography and biological evolution.

The 21-day course began with one and one-half days of intensive on-campus sessions, which laid the foundation for what they would encounter during the immersive field experience.

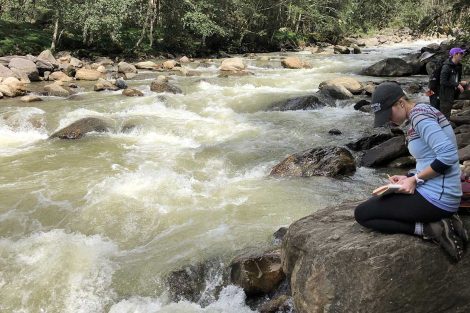

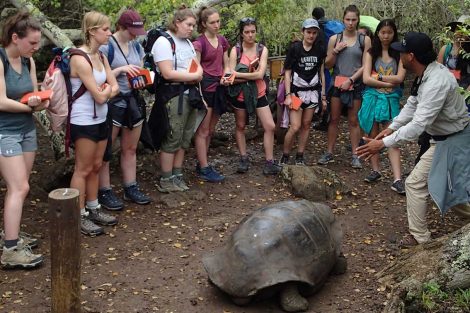

Students climbed Cotopaxi, an active volcano in the Andes Mountains that at just under 20,000 feet is one of the highest volcanoes in the world. Students reached 16,000 feet (shown here), a challenging feat due to the thin air at this altitude, but worth the effort: A half-mile walk around the volcano rewarded students with a close-up view of a tropical glacier. Students interpreted the geological evolution required to create the stunning rock exposure behind them. “This tells us about mountain building,” Malinconico says. “Folding and faulting of this rock formation has resulted in significantly increasing the thickness compared to the original rock layers.” Avery Nunn ’20, an English major, sketches on the side of the Rio Quijos, which eventually drains into the Amazon. The river has eroded deep into the Andes, revealing some of the metamorphic rock at the mountain core. Professors noted here that vegetation changes substantially from their prior location even though the elevation is virtually the same. “On the west side of the Andes ridge, it is dry and arid,” says Sunderlin. “On the east, it is wet and lush.” Malinconico shows students different types of tephra deposits, including those from pyroclastic flows, from past volcanic eruptions from Cotopaxi volcano. “Pyroclastic flows can be one of the most destructive types of volcano activity,” he says. The group spent a day at Chimborazo; the mountain’s summit is the highest point from the center of the Earth. “It is further than Mt. Everest’s peak because of the equatorial bulge of the not-so-perfect spheroid shape of the Earth,” Sunderlin says. Students crossed a footbridge across a canyon in Banos that has been cut by the Pastaza River. It provides an exposed look at the inner makeup of the Andes Mountains. Using a field book is a core component of this course (and all geology field curricula at Lafayette). “Students have to sketch and describe what they see and use their growing geological understanding to interpret the geological evolution of the landscape,” Sunderlin says. “You can take a picture and not understand what it is you are taking a picture of,” Malinconico says. “When sketching, you need to be mindful. You aren’t just drawing, you are annotating and documenting.” On San Cristobal Island, a statue of Charles Darwin marks where the “father of evolutionary theory” supposedly first stepped foot on the Galapagos Islands in the 1830s. “Darwin’s recollections of his time here were formative for the development of his grand theory,” Sunderlin says. “His observations of the variation of life forms from island to island founded many of his views. It’s a place of historical significance.” Students had the chance to snorkel in the cove on San Cristobal where Charles Darwin presumably came ashore for the first time. A park guide in the Galapagos explains how the park system is working to reestablish the tortoise population. The students hike out to Sierra Negra volcano on the island of Isabela. The hiking at various volcanoes in both the Andes and the Galapagos allow them to appreciate the size and shape differences between them and to understand how this is related to the different tectonic settings. Students examine the 2003 eruptive vent on Sierra Negra; the volcano also erupted from a different vent in 2018. “One of the great things about this course is we get to look at a variety of styles of volcanoes,” Malinconico says. “The volcanoes in the Andes tend to be very explosive, while the volcanoes in the Galapagos tend to be effusive or passive. Students are able to understand how the volcanic morphology is a function of the style of eruption and relate both to the very different tectonic settings.”