Professor-student research team takes modernist cuisine technique to new level

By Bryan Hay

Imagine an array of tasty liquids transformed by a chemical reaction into tiny squishy spheres with the look and texture of fish eggs.

Pop them in your mouth and behold a sensation of a mini gusher of sweet or savory as the hardened shell gives way to a squirt of delight.

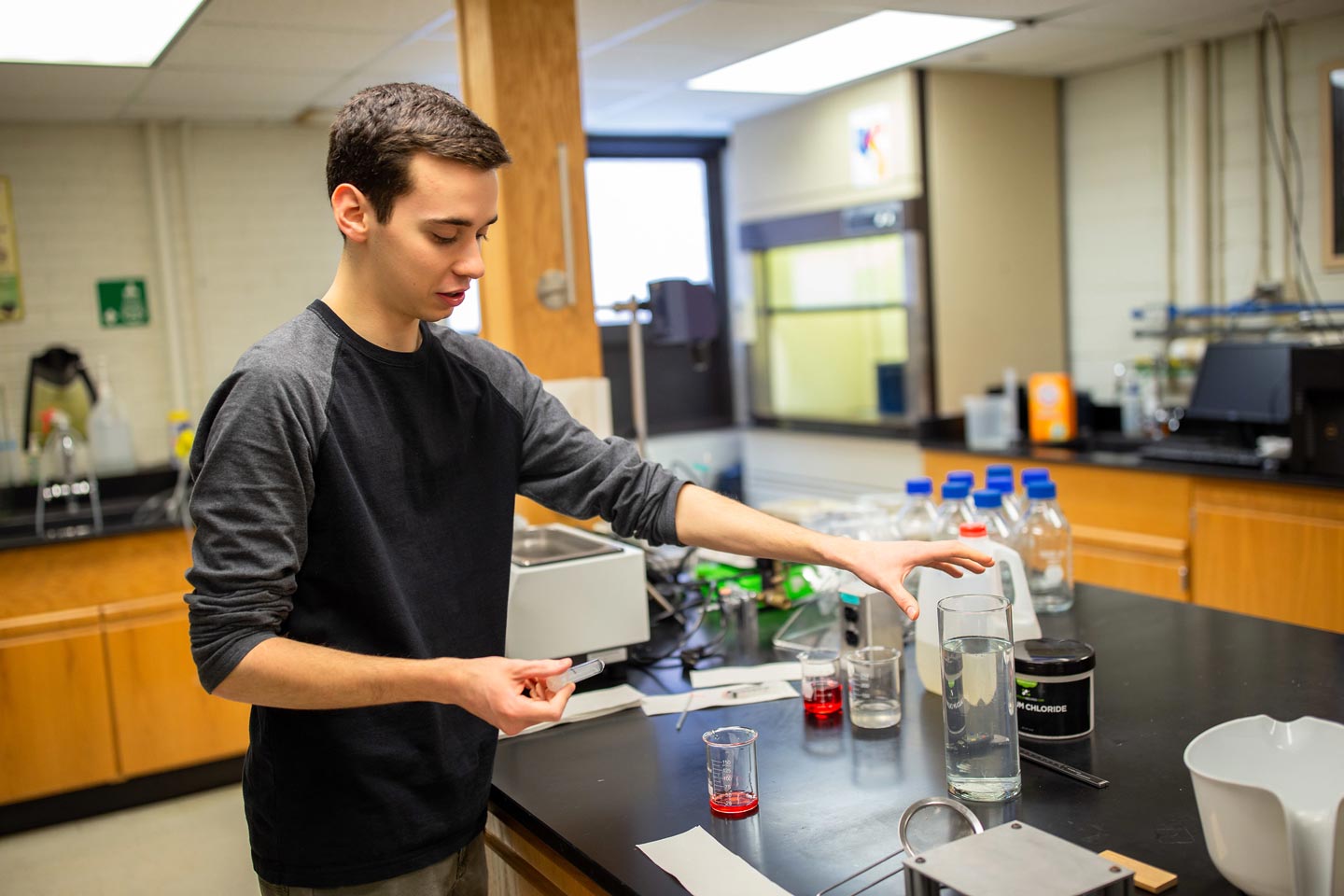

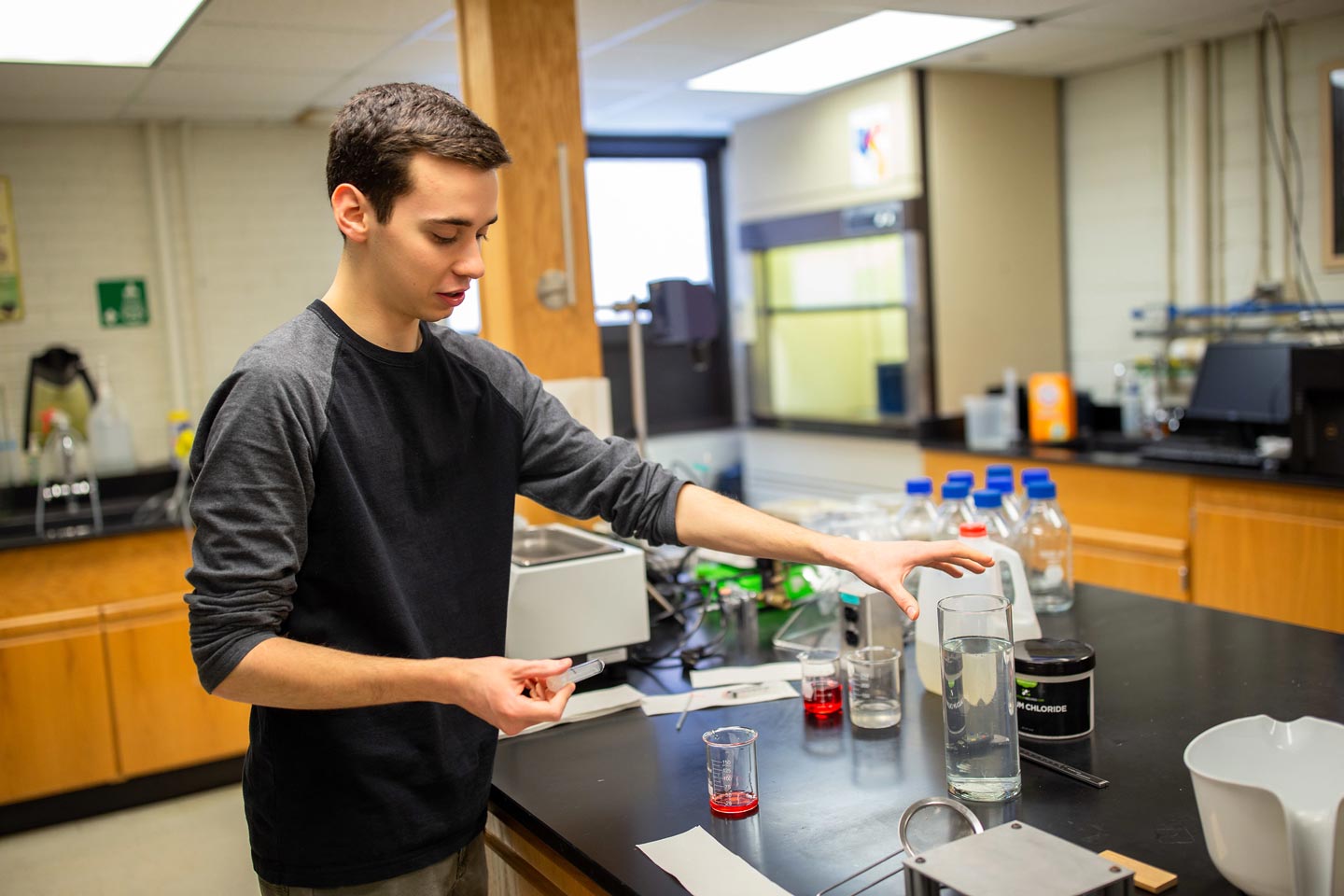

Bon appétit, courtesy of the food spherification research by Polly Piergiovanni, professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, and David Goundie ’20 (chemical engineering).

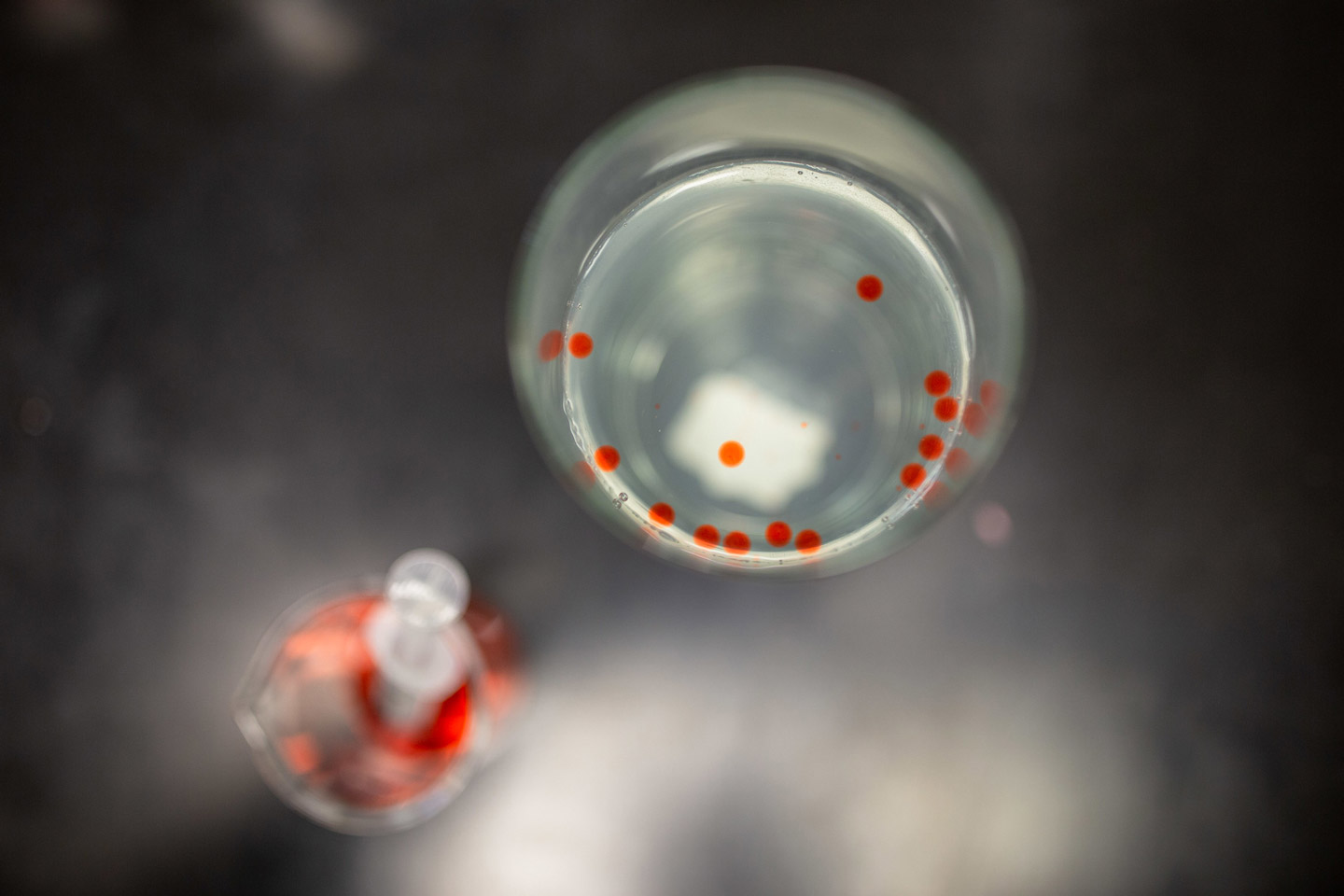

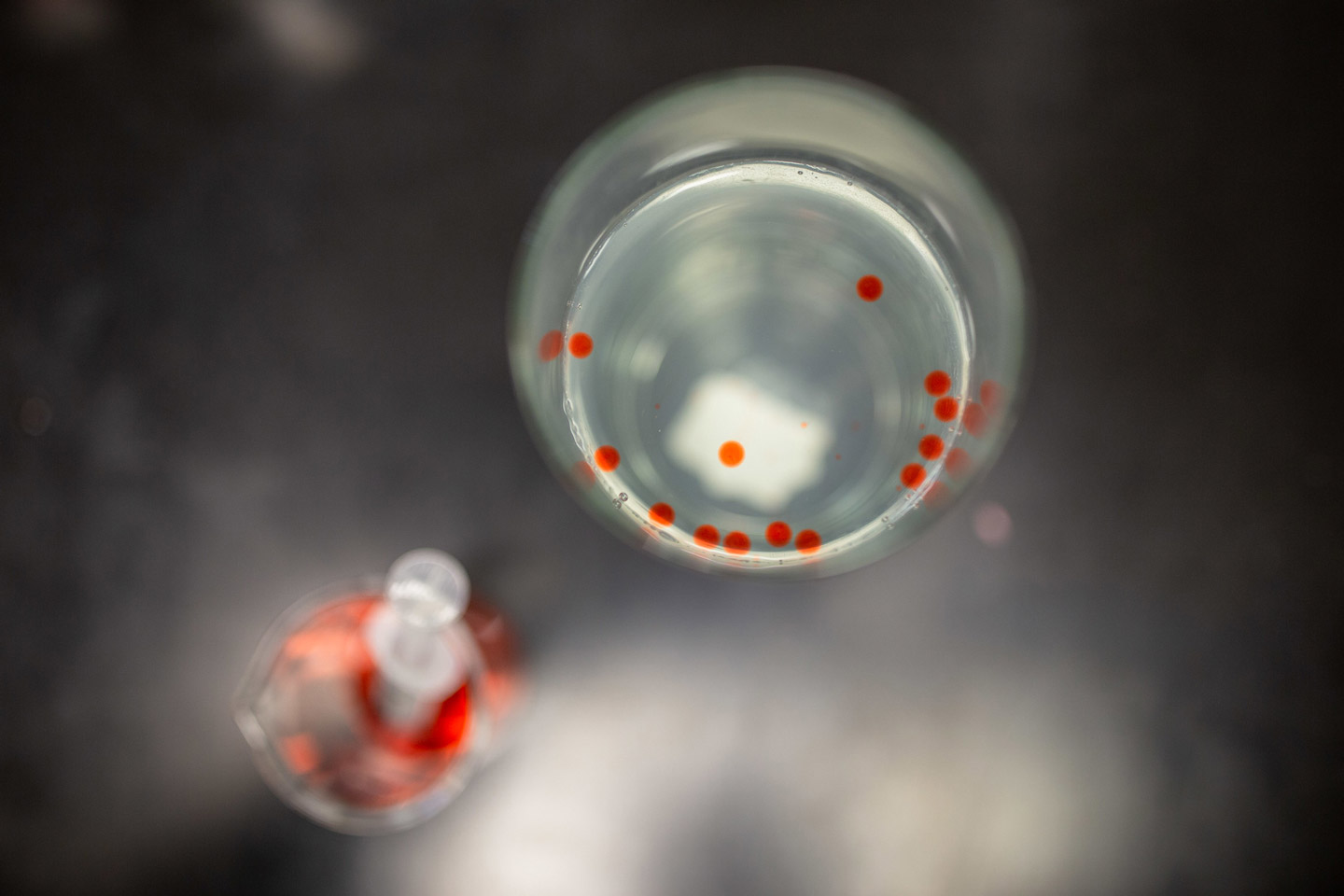

The magic happens when a mixture of sodium alginate, derived from seaweed, and liquid food—tea, maple syrup, honey, hot sauce—is dripped into a bath of calcium chloride solution using a syringe or pump. Moments later, the food is transformed into colorful, spherical globules, ready, after a quick rinse and a towel dry, for plating with an entrée or tossing in the mouth.

The magic happens when a mixture of sodium alginate, derived from seaweed, and liquid food—tea, maple syrup, honey, hot sauce—is dripped into a bath of calcium chloride solution using a syringe or pump. Moments later, the food is transformed into colorful, spherical globules, ready, after a quick rinse and a towel dry, for plating with an entrée or tossing in the mouth.

The modernist cuisine technique was invented in the 1940s by food scientist William Peschardt, who sought to create edible artificial cherries. Piergiovanni and Goundie are taking that to a new level, researching ways to control the diameter and firmness of the spheres using different tubing diameters and adjusting the concentrations of calcium chloride.

So far, they’ve determined that the most satisfying bursts for consumption have firmness values that represent a compression of 34-40 percent.

“It hardens from the outside in and forms a small sphere and retains its shape,” Goundie says as he demonstrates with a solution of water and red food coloring. “Depending on how long you keep it in the solution, the center of the sphere will remain a liquid with a solid outer shell.”

“It hardens from the outside in and forms a small sphere and retains its shape,” Goundie says as he demonstrates with a solution of water and red food coloring. “Depending on how long you keep it in the solution, the center of the sphere will remain a liquid with a solid outer shell.”

Restaurants and molecular gastronomists are using the technique to make the spheres small enough to eat so they explode in your mouth.

“It’s like a gusher with a liquid center,” Piergiovanni adds. “David tried a lot of food during his work last summer. A classic is hot sauce, which you can put right on nachos.”

Goundie got his first taste of food spherification during an introduction to engineering course taught by Piergiovanni. She used food as the vehicle to introduce chemical engineering, and food spherification was one of the projects. Inspired, Goundie talked more with Piergiovanni to see if there was a statistical angle for the experiments.

“Talking together, we came up with the idea of looking for a way to make the best squishy sphere,” she says.

“Talking together, we came up with the idea of looking for a way to make the best squishy sphere,” she says.

Their research has implications beyond the culinary realm. It has the potential to aid patients with difficulties with drug delivery because medications could be encapsulated in a food sphere and diffused through its outer shell for timed release, Goundie explains.

To make successful food spheres, the liquid cannot contain calcium and cannot be too acidic, Piergiovanni says. Food spheres kept in calcium chloride and stored in a refrigerator will maintain their shape and texture for several days.

Liquids that have performed particularly well in the Piergiovanni-Goundie test kitchen include chocolate syrup, caramel syrup, soy sauce, and Fanta.

Liquids that have performed particularly well in the Piergiovanni-Goundie test kitchen include chocolate syrup, caramel syrup, soy sauce, and Fanta.

“We’ve tried using a bigger opening in the pump, but we had blobs rather than spheres,” the professor laughs. “It’s just magical to watch.”

The magic happens when a mixture of sodium alginate, derived from seaweed, and liquid food—tea, maple syrup, honey, hot sauce—is dripped into a bath of calcium chloride solution using a syringe or pump. Moments later, the food is transformed into colorful, spherical globules, ready, after a quick rinse and a towel dry, for plating with an entrée or tossing in the mouth.

The magic happens when a mixture of sodium alginate, derived from seaweed, and liquid food—tea, maple syrup, honey, hot sauce—is dripped into a bath of calcium chloride solution using a syringe or pump. Moments later, the food is transformed into colorful, spherical globules, ready, after a quick rinse and a towel dry, for plating with an entrée or tossing in the mouth. “It hardens from the outside in and forms a small sphere and retains its shape,” Goundie says as he demonstrates with a solution of water and red food coloring. “Depending on how long you keep it in the solution, the center of the sphere will remain a liquid with a solid outer shell.”

“It hardens from the outside in and forms a small sphere and retains its shape,” Goundie says as he demonstrates with a solution of water and red food coloring. “Depending on how long you keep it in the solution, the center of the sphere will remain a liquid with a solid outer shell.” “Talking together, we came up with the idea of looking for a way to make the best squishy sphere,” she says.

“Talking together, we came up with the idea of looking for a way to make the best squishy sphere,” she says. Liquids that have performed particularly well in the Piergiovanni-Goundie test kitchen include chocolate syrup, caramel syrup, soy sauce, and Fanta.

Liquids that have performed particularly well in the Piergiovanni-Goundie test kitchen include chocolate syrup, caramel syrup, soy sauce, and Fanta.