What I’m teaching

Imagined Climates (a course on climate fiction, climate poetry, and climate art)

Voices of Environmental Justice (a course on how writers and artists around the world draw attention to environmental crises and injustices)

What I study

I’m trained as a literature scholar, and more broadly, in the emerging field of the environmental humanities. I examine how stories, ideas, and modes of thinking impact our sense of a place or our sense of the planet. My current research focuses on literary portrayals of climate change and fossil fuel consumption in global literatures of the 20th and 21st centuries.

What drew me to Lafayette

I’m very excited to be joining an interdisciplinary program, and I’m looking forward to working with my colleagues in the sciences and social sciences. Moreover, I was drawn to Lafayette because of the College’s commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2035 through the Climate Action Plan. As a scholar who studies the climate crisis and spends most of her time thinking about climate change, I appreciate working at a campus that takes that seriously. I want to teach students to not only consider climate change intellectually but also to consider how we alter our lives in the face of this knowledge.

What students can expect from me

Sometimes students entering an environmental literature class have the misperception that we are going to devote our time to reading beautiful poetry about trees and flowers and birds. We will do some of that; nature writing is a fascinating field in its own right. But students in my classes can expect to think much more about environmental justice and the way that human inequalities impact environmental problems. We study how toxicity impacts human health, particularly the health of those who live in poor communities or communities of color. Most questions of environmental justice are questions of human justice. That’s the lens that students can expect to encounter in my courses.

What you may not expect from me

I read a lot of books that are neither classics nor particularly well-written. For example, I recently published an article about a Finnish murder mystery called The Healer, set in futuristic Helsinki. It’s about a serial killer who is killing all of the corporate executives who he feels contributed most to climate change. I think detective novels like this can be a great way to think about questions of responsibility and guilt and culpability. Murder mysteries are set up with the presumption that there is one villain, and if we can find that one villain, we can solve the crime. But climate change is a lot more complicated than that, and it’s disrupting our easy narratives of guilt and innocence.

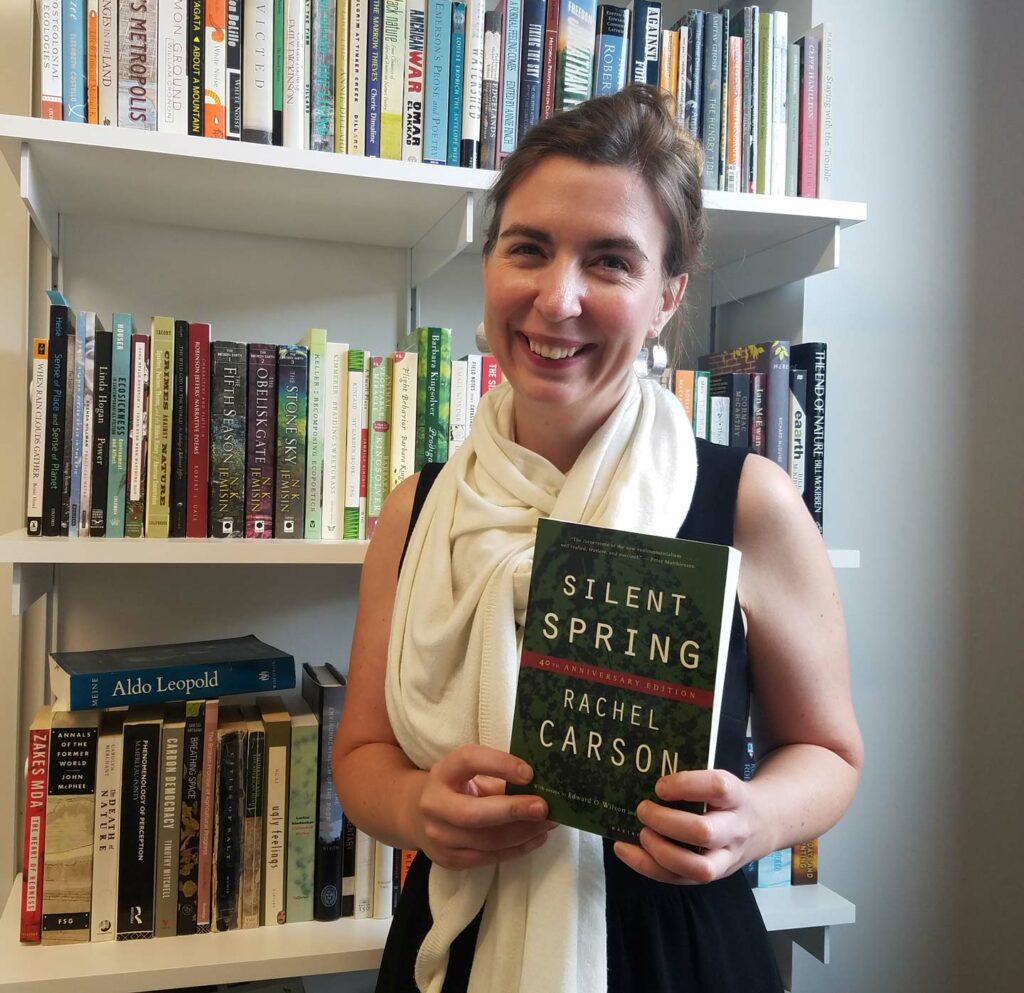

What I’m holding

What I’m holding

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, published in 1962. For me, this book is an example of how meticulous research and lucid, compelling writing can produce environmental change. We are all living in a post-Rachel Carson world, and we owe her so much. This book influenced the creation of the Environmental Protection Association and energized the environmental movement. But Carson was harshly criticized for doing this type of work as a female researcher in the mid-twentieth century. That history is an enduring example of how social inequities impact which voices we hear on environmental topics.

What I’m holding

What I’m holding