Criminal justice reform advocate Yusef Salaam, one of the ‘Exonerated Five,’ gives Black Heritage Month keynote address

By Stella Katsipoutis-Varkanis

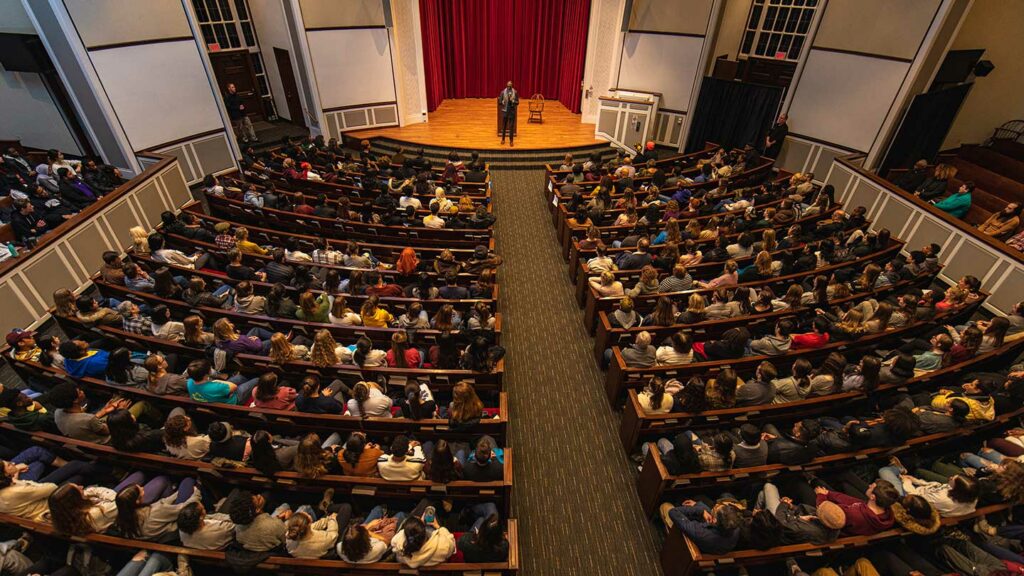

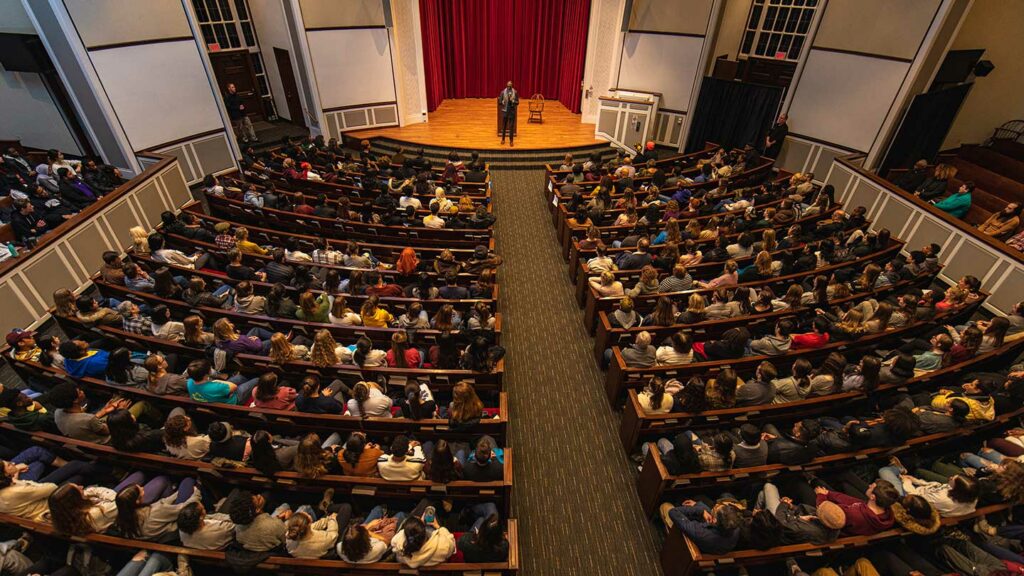

Yusef Salaam, one of the exonerated “Central Park Five,” was met with a standing ovation as he greeted a packed Colton Chapel Feb. 16. A writer, motivational speaker, and criminal justice reform advocate who has dedicated his life to educating the public on issues such as wrongful incarceration, false confessions, press ethics, and police misconduct, Salaam visited Lafayette to deliver a powerful keynote speech in honor of Black Heritage Month.

Salaam recounted what it was like to serve time for a crime he did not commit, and how his faith helped him not only survive the harrowing experience, but also thrive so that he could help others after his liberation.

“In 1989, I was run over by the spiked wheels of justice. It laid us out flat,” he began. “I didn’t get a chance to hear the powerful words of the great philosopher Cardi B until a little later on in life. What she said was, ‘Fall down nine times, get up 10.’ I say, ‘Thank you, Lord, for the blessings, and thank you, Lord, for the lessons.’”

On April 19, 1989, Trisha Meili—a white 28-year-old investment banker—was brutally assaulted, raped, and left for dead while jogging in New York City’s Central Park. Meili, who was in a coma for 12 days after her attack, had no recollection of the incident when she came to. After initial investigations, police took five youths—four African American, one Latino—into custody for the crime: Salaam, Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Korey Wise, and Raymond Santana.

The teens, who became collectively known as the “Central Park Five,” were ultimately tried and convicted in a case that brought racial tensions to a climax throughout the city. In 2002, convicted murderer and serial rapist Matias Reyes confessed to the crime, and the unidentified DNA found at the scene—which was never linked to any of the Central Park Five—finally found its match. The boys’ convictions were overturned, and they were exonerated. At that point, Salaam—only 15 years old at the time of his conviction—had already served more than six years in prison.

This is his story as he shared it with the Lafayette audience.

Confessions

Despite not having any proven physical evidence tying Salaam and his peers to the crime, the prosecution used one main weapon to secure a conviction in the Central Park Five trial: their false confessions. After being inhumanely interrogated by police at the outset of the investigation—receiving no food, water, or sleep for hours—the boys were coerced into confessing. But not Salaam.

“My mother said to me, ‘Stop talking to them. They need you to participate in whatever it is they’re trying to do. Do not participate. Refuse,’” Salaam said. “She was teaching me what it meant to resist. I was the only one who hadn’t made a written or videotaped confession.

“Those false confessions that were received by the public, they looked at and said, ‘Wow, this is a slam dunk.’ But when we were in [The Central Park Five, a documentary directed by Ken Burns, Sarah Burns, and David McMahon and released in 2012], it gave us our voices back. As Santana reads his false confession [in the film], he looks up and says, ‘What 14-year old boy talks like this?’ It was the first time the public got the opportunity to understand how much of a debacle this was.”

The false confessions were used as evidence in court—even though they were not consistent with each other—alongside inadequate forensic evidence. The media coverage of the trial, Salaam explained, also painted an inaccurate picture of the teens following their confessions, greatly influencing the trial and its outcome.

Even current President Donald Trump, then a business tycoon and real estate developer, placed a full-page ad in New York City’s leading newspapers in 1989, calling for the reinstatement of the death penalty in response to the Central Park Five case. The ad read, “BRING BACK THE DEATH PENALTY. BRING BACK OUR POLICE!”

“I want everyone to understand what this ad represents,” Salaam said. “This was a whisper into the darkest enclaves of society.”

The most difficult thing for Salaam to come to terms with was the anger he encountered in the courtroom as a result of the media backlash.

“Every single day, I would go back and forth to court as if it was a job. And every day, they would be looking at me with this hatred in their eyes that I couldn’t reconcile,” he said. “I kept trying to figure out what they were looking at and why.”

Conviction

Salaam remembers the day of his conviction clearly.

“I was in the hallway talking to a loved one [on the phone],” he said, “and someone came running into the hallway saying, ‘They got the verdict.’ And I told the person I was on the phone with, ‘I’ll see you soon.’ When I went into that courtroom, and when the jury foreman stood to read the verdict, I heard the words echo so many times in the courtroom I lost count. It kept saying guilty … guilty … guilty. They led us to the back, and there we cried. It was painful.”

He was sentenced to five to 10 years in prison—the maximum penalty he could receive at his age. It was when presiding judge Thomas Galligan asked him if he had anything to say before his sentencing that Salaam spoke his mind in the face of the prosecution, with a rap song he had written.

“It was the first time I realized I could stand and say something for myself,” he said. “I remember I began to rise in those same eyes that were looking at me, when all of that hatred became strength right in front of my face. There I was, towering before them, and I began with the words of my hero, Malcolm X: ‘I’m not going to sit here at your table and watch you eat, and call myself dinner … ’

“The judge was so angered by my words. When the reporters took a photo of my rap song, that photograph found its way to the front of the newspaper. My photograph, of my rap song, and it said on the New York Post, ‘Salaam Bologna.’ It was a slap in the face.”

However, the worst part of the conviction, according to Salaam, was that the true perpetrator was still on the loose.

“Because they got stuck with a mistake, the real criminal was out committing more crime,” Salaam said. “One of his last victims was a young pregnant Latina woman. He raped her and stabbed her to death, killing her and her unborn child. Had the system understood that they had the wrong people, that young lady would have been alive. That’s the collateral effect of getting it wrong.”

Incarceration

After Salaam was sent to a maximum-security prison shortly thereafter, an officer approached him and asked him a seemingly innocuous question: “You’re not supposed to be here. Why are you here? Who are you?” It was this question that allowed Salaam to take the harsh reality of being an innocent man imprisoned and transform it into an opportunity for growth.

“This simple question was the question that changed the total trajectory of my life,” Salaam said.

Keeping his Islamic faith close to his heart, Salaam soon realized that while his circumstances were indeed tragic, prison was exactly where he was destined to be.

“Each of us came into this world the same way,” he said. “We each were one of more than 400 million options. That means because we made it, we have a purpose. I remembered my mother said I came into this world without a name. On my birth certificate, it actually said, ‘Boy Salaam.’ My parents were to observe me for seven days, and throughout this process the question they had to answer themselves was ‘Who is this?’ On the seventh day, my parents told the people for the first time that my name was to be Yusef Salaam.

“When I was in prison, imagine my surprise that when I read the Bible, there was a young man named Yusef. This same story found its way in the Qur’an. The most interesting thing about this story is that this young man who was chosen by God went to prison for a crime that he didn’t commit, and that crime was murder. This young man came home free. I thought God was talking to me. I said, ‘I’m going to get out of here a free man.’”

While serving his time in prison, Salaam found comfort in writing poetry and used that time to earn a GED diploma and associate degree. He also drew strength from letters from his grandmother, who addressed him as “Master Yusef Salaam” in each of her messages.

“She was telling me that I was the master of my fate,” he said. “She was guiding me and planting my seeds so that I can remember my greatness. Prison life, they say, in many ways, can be likened to the womb. If the life inside becomes stillborn, the womb becomes the tomb. In my determination to make sure I did not die, I did the time, and I refused to let time do me.”

Exoneration

More than six years later, Salaam’s faith that his imprisonment had a greater purpose proved to be true. Reyes confessed to the crime in 2002, and further testing revealed DNA found at the crime scene did indeed belong to him. Reyes was sentenced to life in prison, and the Central Park Five were exonerated after their convictions were overturned. In 2014, the five received a $41 million settlement in a lawsuit they filed against the City of New York for its injustices against them.

Having his name finally cleared, however, did not make it any easier for Salaam to assimilate back into life outside prison.

“I came home to be identified as a level three sexual predator,” Salaam said. “I came home wanting to hide in plain sight. Then [in 2013] the movie came out, The Central Park Five. I’ll never forget how afraid I was when the film came out, because it was coming to my town, and I didn’t know what they would think.”

Salaam was awarded an honorary doctorate and also received a Lifetime Achievement Award from former President Barack Obama in 2016. In 2018, he also was appointed to the board of the Innocence Project, a nonprofit committed to exonerating wrongly convicted people and reforming the criminal justice system.

Last year, Netflix released a feature limited series called When They See Us, which was directed by Ava DuVernay and is based on the story of the Central Park Five. The film garnered more than 23 million viewers. In an interview after the series debut, Oprah Winfrey rebranded the “Central Park Five” as the “Exonerated Five,” as they are now known.

Lesson

Today, Salaam is able to reflect on his experiences with little bitterness, but with much faith, positivity, gratitude, and determination to use the lessons he has learned to educate others.

“If you readjust your focus, you’ll realize that the Central Park Jogger case is a love story between God and his people,” Salaam said. “It’s a story of a criminal system of justice turned on its side and placed on trial in order to produce a miracle in modern time.”

One of Salaam’s most important goals as a motivational speaker and criminal justice reform advocate is to enlighten those pursuing legal professions about the devastating effects of wrongful imprisonment, police coercion, and racial injustice.

“On the side of cop cars throughout the nation, I’ve seen the words, in some variation, ‘To serve and protect.’ In New York, they have the words ‘Courtesy, Professionalism, and Respect.’ But if you happen to remember that young man on Staten Island named Eric Garner, they didn’t even give him the first letters off of the cop car … They didn’t give him CPR [when he told police he couldn’t breathe]. We have to plant seeds in the minds of future police officers, future judges, future prosecutors, future citizens, so that we change the world into a better place.”

Salaam’s final message to students: to conquer their fears and be unafraid.

“If you do what’s hard now, you will have an easy life. If you do what’s easy now, you’re going to have a hard life,” he said. “Do what you have to so that you can do what you want to. You will appear to have a lucky life. Luck is an acronym that stands for ‘laboring under correct knowledge.’ Sometimes you find yourself in darkness. The light is inside you, and you can illuminate your own darkness and shine your light on the world.”