Steven Belletto explores how the Beat Generation changed American literature and culture

By Stephen Wilson

A murder launched a movement.

Not the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, which set off #BlackLivesMatter. Not the Parkland, Florida, school shooting, which helped form March For Our Lives. This death was of David Kammerer.

Who, you might ask?

His murder birthed the Beat Movement.

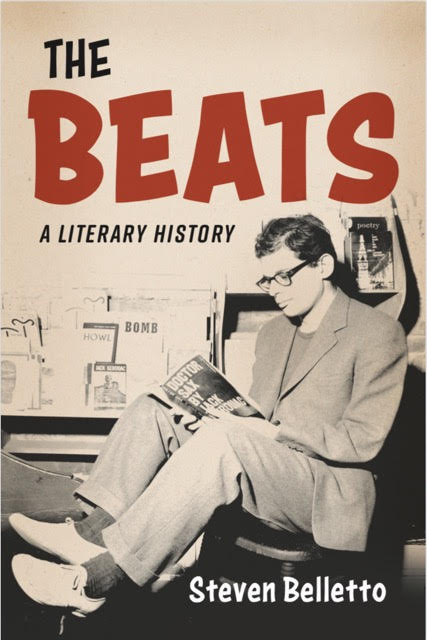

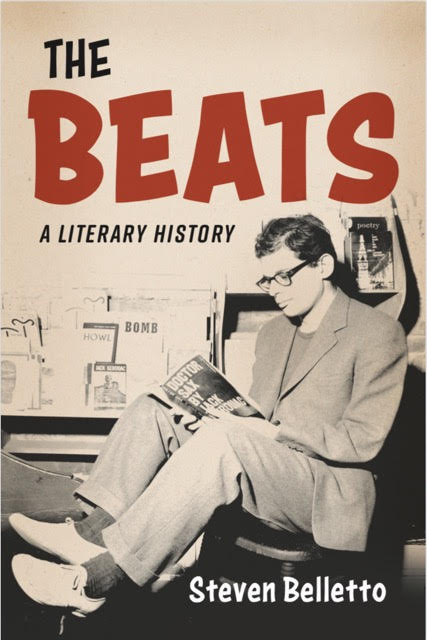

The story of his death and ramifications of it for the well-known triumvirate at the core of the Beat Generation—William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, and Allen Ginsberg—serve as the hook into a new book, The Beats: A Literary History, by Steven Belletto, professor of English.

While many people are familiar with the most famous Beat writing (Kerouac’s novel On the Road, Ginsberg’s poem Howl, and Burroughs’ novel Naked Lunch), Belletto’s book shows how the Beat movement was more widespread and introduces readers to lesser-known though significant writers. In fact, while many studies of the Beats focus on biographical recaps of the trio’s salacious life details, Belletto analyzes their literary achievement, which has made a lasting impact on American letters.

“The book focuses on the literary aspects of the movement,” says Belletto. “While the work of Burroughs, Kerouac, and Ginsberg feature prominently in the book, it also presents a larger field of vision on the writers and communities that formed in and came out of the movement they began.”

The murder of Kammerer plays a central role in the book’s opening pages because it was the first subject that Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Burroughs collectively wrote about.

The murder of Kammerer plays a central role in the book’s opening pages because it was the first subject that Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Burroughs collectively wrote about.

The murder took place in 1944 and was represented in the media and in the legal system as a “honor slaying” with a young man protecting himself from an older gay male. Details of what happened and the motive remain murky, but the perverse moral order of mid-century America seemed to make those details unnecessary …

Unnecessary except to those writers who knew the victim and the assailant; those writers whose own representations of the event evaded the dominant story by offering alternate representations of it, thereby questioning the “official” explanation for the murder. A young Allen Ginsberg began a novel about the murder, and Kerouac and Burroughs collaborated on another novel titled And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks. What is striking about those works is how they push back against stories about the murder circulating in the media at that time.

“We have a group of writers emphasizing the precarious relationship between language and ‘the real’ in an attempt to define themselves against representations by the media, which served as a mirror and mouthpiece of dominant culture,” says Belletto. “There is also the sense that these competing representations are not merely semantic squabbles, but that they have serious consequences in people’s lives.”

Another central motif for the Beats was their refusal to accept cultural norms and literary standards that didn’t apply to their values and experiences. “This is a generation of writers who made the counterculture visible by evading the dominant culture, and then writing about this evasion in exciting and innovative ways” says Belletto. “This writing invigorated a stale literary culture in the United States, and was broadly accessible to young people hungry for new forms of expression that spoke to their experiences.”

Another central motif for the Beats was their refusal to accept cultural norms and literary standards that didn’t apply to their values and experiences. “This is a generation of writers who made the counterculture visible by evading the dominant culture, and then writing about this evasion in exciting and innovative ways” says Belletto. “This writing invigorated a stale literary culture in the United States, and was broadly accessible to young people hungry for new forms of expression that spoke to their experiences.”

Beyond Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Burroughs, the book discusses dozens of writers who carved out their own sense of Beatness and Beat literature. This includes well-known figures such as Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), Gary Snyder, Gregory Corso, Diane di Prima, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, as well as lesser known or even forgotten poets and novelists, such as Elise Cowen, Kay Johnson, Ray and Bonnie Bremser, and Sheri Martinelli. There is also special emphasis on women writers associated with the movement, including Lenore Kandel, Barbara Moraff, Joyce Johnson, and Hettie Jones. The book offers a field-defining analysis of these and other writers, and explores how the idea of “Beat” or “Beatness” circulated in underground magazines, hipster communities, and countercultural political expression.

“In the 1940s and 1950s, the Beats struggled to articulate their unique visions in a dominant culture that rejected them,” says Belletto. “At first, they had trouble finding publishers and were ridiculed by those in the academy. But after they broke through into culture, they changed how people understood ‘literary’ writing, not only what it could look like but the sorts of people and experiences it was OK or not OK to write about. Contemporary culture in the U.S. owes a lot to the Beat movement, even as we don’t necessarily realize that.”

Beat expression was not meant to topple dominant culture but to offset it, challenge it, and shade it in.

As Beat writer John Clellon Holmes said, even in “the wildest hipster, … there is no desire to shatter the ‘square’ society in which he lives, only to elude it.”

The murder of Kammerer plays a central role in the book’s opening pages because it was the first subject that Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Burroughs collectively wrote about.

The murder of Kammerer plays a central role in the book’s opening pages because it was the first subject that Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Burroughs collectively wrote about. Another central motif for the Beats was their refusal to accept cultural norms and literary standards that didn’t apply to their values and experiences. “This is a generation of writers who made the counterculture visible by evading the dominant culture, and then writing about this evasion in exciting and innovative ways” says Belletto. “This writing invigorated a stale literary culture in the United States, and was broadly accessible to young people hungry for new forms of expression that spoke to their experiences.”

Another central motif for the Beats was their refusal to accept cultural norms and literary standards that didn’t apply to their values and experiences. “This is a generation of writers who made the counterculture visible by evading the dominant culture, and then writing about this evasion in exciting and innovative ways” says Belletto. “This writing invigorated a stale literary culture in the United States, and was broadly accessible to young people hungry for new forms of expression that spoke to their experiences.”