Program engages students in engineering as a liberal art, recognizing and examining challenges through multidisciplinary perspectives

By Bryan Hay

For 50 years, the engineering studies program has put students on a path to adventurous careers from environmental fields and consulting to construction management and digital industries, approaching challenges with a solid grounding in engineering and the liberal arts.

Created with the goal of producing graduates who could bridge the gap between engineering and the liberal arts, the program’s current mission is to engage students in engineering as a liberal art, recognizing the increasingly complex challenges of sociotechnical systems and examining these systems through multidisciplinary perspectives.

The program helps students gain expertise in examining the place of engineering and technology in society, with interdisciplinary skills to lead public technology debates around issues related to policy, management, economics, and the environment.

Students are equipped with foundation courses in chemistry, economics, engineering, and calculus, electives in engineering systems courses, and hands-on experience with internships and focused independent studies.

As a result, students who graduate with a degree in engineering studies are hardwired into Lafayette’s rich liberal arts and scientific traditions and well prepared to accept interdisciplinary challenges related to how science and technology affect society.

About 900 graduates hold A.B.-Engineering degrees.

“There are so many alumni doing so many amazing things,” says Benjamin Cohen, chair of engineering studies and associate professor.

“We’ve been extraordinarily successful. Students go into various professions; they head to med school, law school, and business school; they go into education. Because the program provides more flexibility for students to tailor their courses than other engineering degrees, it’s hard to point to just a few paths after graduation. We have good job placement, with starting salaries in the top 10 for Lafayette grads,” he says. “With only two tenure track faculty, we do a lot with a little, graduating 18 to 20 students a year. So our graduates per faculty are near the top at the College.”

It’s been suggested that the degree program is a different way to train engineers, says Julia Nicodemus, associate professor of engineering studies.

Being interdisciplinary means folding technical and nontechnical courses together, she notes.

“That happens inside the engineering studies classroom, but also for the many students who have double majored in almost every other program on campus, with economics, government and law, art, the sciences, and foreign languages as most common,” Nicodemus says. “That has helped them land careers on Wall Street, in Silicon Valley, and with large multinational consulting firms and government agencies.”

A U.S. Environmental Protection Agency engineer, Britney McCoy ’05 (engineering studies and government & law) was undecided about what type of engineering she wanted to pursue when she arrived at Lafayette. Guided by faculty mentors, she was encouraged to think about social engineering, not in the literal sense but rather as a way to combine her interests in policy and law, urban planning, and geographical information systems.

Britney McCoy ’05 at Port of Los Angeles as part of her work at EPA.

“Engineers can be used to help solve problems across a variety of sectors. And so that’s the way I started thinking about it,” says McCoy, who works on the implementation of the Diesel Emissions Reduction Act, which protects human health and improves air quality by reducing harmful emissions from diesel engines.

“By my junior year, I had declared the engineering studies major because of that influence,” she says.

Because of her engineering studies foundation, McCoy, who holds a Ph.D. in engineering and public policy from Carnegie Mellon University, approaches her work through a holistic lens.

“I would best describe it as being able to communicate technical issues to a layperson and how to help multiple stakeholders understand the impacts of engineering decisions, whether it’s in the construction environment or addressing water and air quality issues,” she says.

Often, students who choose to major in engineering studies want a technical background but want to use that as a basis for doing broader work, Cohen says. It means taking technical electives but choosing to connect that engineering background with more courses across campus rather than drilling down two or three classes in the technical direction.

“They want to use that technical background, almost always, to bring it elsewhere,” he says. “We talk about it as a kind of bilingual skill. They can speak engineering, and they can speak economics; they can speak thermodynamics and public policy; or they’re the ones who can, say, carry the conversation about social justice and technology in a room of investors and computer coders, helping make it clear how technology is cultural.”

“Everyone is increasingly seeing the importance of the interdisciplinarity and the interconnectedness of things,” says Kristen Sanford, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering and past chair of engineering studies.

“So, in the engineering studies program, we really are focused on thinking about sociotechnical problems and sociotechnical solutions,” she says. “And I think that that perspective will continue because people are increasingly seeing things that way, as opposed to a time when engineers tended to see everything as technical problems.”

When Joe Ingrao ’16 arrived at Lafayette, he was unsure which of the engineering disciplines he wanted to follow.

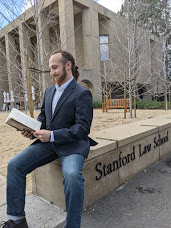

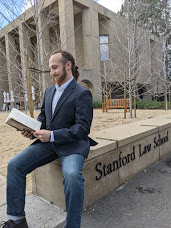

Joe Ingrao ’16

“In my First-Year Seminar with Prof. Cohen, I started thinking a lot about the relative number of technical experts in society versus the necessity of having people who can bridge the technical worlds with the humanities, things like law and policy, and economics,” he recalls. “I decided that my skills would go better into the latter category.”

Ingrao, who double majored in engineering studies and Asian studies, with a minor in anthropology and sociology, would later discover how his engineering studies degree led him on a path toward a law degree. This spring, he will receive his J.D. from Stanford Law School and a Master’s of Science in environment and resources from Stanford School of Earth, Energy, & Environmental Sciences.

After Lafayette, Ingrao spent a year as a farmhand, pondering what advanced degrees he might pursue.

“I decided that the interdisciplinary thinking that I was used to and always enjoyed with engineering studies could be put to really good use in the law,” he says. “The legal world itself can determine outcomes in many important issues. Engineering studies and the liberal arts coursework at Lafayette gave me an understanding of the world and prepared me for law school.”

Like his varied experiences at Lafayette, his budding law career has touched on many interests. Although he’s planning to practice environmental law and served as law clerk for Earthjustice, a nonprofit environmental law organization, Ingrao also interned with the American Civil Liberties Union of Maryland and has studied civil rights issues and constitutional law.

As engineering studies moves into its next 50 years and beyond, he can imagine how the program will prepare students to take on difficult issues facing society such as racial and social injustice.

“I went to Earthjustice specifically because I knew they were doing a lot of work with low-income communities of color here in California,” Ingrao says. “Over the summer, I had the chance to help community members deal with local air quality issues and environmental justice issues, areas that traditionally have not been the primary focus of environmental lawyers.

“The holistic thinking of the engineering studies major really made me gravitate more toward social justice issues of today,” he adds. “It widened my perspective and thinking.”

It’s a dual relationship about how engineering and technology influences society and how society influences engineering and technology, Sanford adds.

“For all of our students, no matter where they end up working, they have that background, and that perspective, and some pretty powerful experiences in those courses where they’re doing projects,” she says. “And, you know, in many cases, I’m presented with things that I’ve just never thought about before.”

To be sure, there will always be an abundance of technical issues to address.

“But our problems aren’t going to be solved just by technical fixes,” says Sanford, who predicts increasing demand for the engineering studies program. “Certainly, we’ve seen very strong interest in the major. The engineering and public policy course, for example, has been consistently overenrolled. We’re turning students away because we simply don’t have enough capacity for all the students who want to take it.”

The program also has evolved to be a leader in advancing diversity in engineering, says Cohen. “Because we have built strong relationships across campus and with the new Hanson Center for Inclusive STEM studies, we are poised to help the College graduate students who can, for example, lead their industries in issues of racial and environmental justice.”

Sanford echoes the point, noting that one of the important goals of the program is to serve the needs of students by working with colleagues across campus.

“We need to continue to offer and teach courses that are open to all students to help them think about what we need in this country and help our citizens to understand the sociotechnical nature of problems,” Sanford says. “And the more we can do that, the better off we will all be in the long run.”