College exhibit to commemorate 200th anniversary of Lafayette’s Grand Tour of the U.S.

By Bryan Hay

Reaching into its vast collection of Marquis de Lafayette memorabilia, Lafayette College will offer a semester-long exhibit to mark the 200th anniversary of the Revolutionary War hero’s “Grand Tour” of the United States that will reanimate how the young nation received him for the last time.

Normally stowed silently away in shelved boxes and out of the public’s eye, the time capsule of well-preserved pieces from the Marquis de Lafayette’s final, triumphant visit—engraved ball invitations, dinner cards, personal letters to the nation’s founders, sheet music, formal dinner attire, personal pocket-sized items bearing Lafayette’s likeness, and even a ceremonial accessory worn by a member of the Easton delegation who attended Lafayette’s parade in Philadelphia—will be brought to vivid life again.

Curated by Ana Ramírez Luhrs, co-director, Special Collections and College Archives, and assisted by Ricardo Reyes, director of Galleries and curator of Collections, the Return to ‘The Land of Genuine Freedom’ exhibit will be presented in the Williams Center Gallery in Williams Center for the Arts, 317 Hamilton St., Easton, from Aug. 28 to Dec. 6. The gallery is open Wednesday-Sunday from 12-5 p.m. Highlighting the material culture of Lafayette’s farewell tour, the exhibit will focus on his arrival in New York, the balls and parties, the paraded, and a look at the various souvenirs and keepsakes people may have had at home that commemorated Lafayette.

Ana Ramírez Luhrs, co-director, Special Collections and College Archives | Photo by Adam Atkinson

“It’s a real pleasure to work with this material, appreciating the treasures we have here at Lafayette that help illuminate the history of our nation, and, in particular, this important final visit to the U.S. by one of its beloved Revolutionary War heroes,” Luhrs says. “How exhilarating it is to be so close to that history and touching it. The story of Lafayette’s farewell tour of the U.S. comes alive again. It’s so real.”

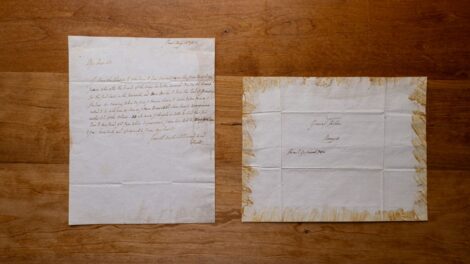

The name of the exhibit is taken from an excerpt in Lafayette’s May 24, 1824, letter to a retired Continental Army officer he served with during the American Revolution in which he describes America as “the land of genuine freedom.” Acquired earlier this year by Skillman Library’s Special Collections and Archives, the rare letter was written just months before Lafayette started his 13-month “Grand Tour” of the United States. It will be included as part of the exhibit.

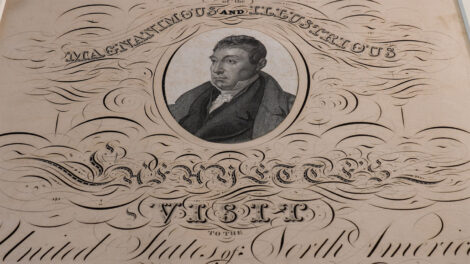

At the invitation of President James Monroe and Congress, Lafayette returned to the United States for the last time in 1824, landing at the southern tip of Manhattan on Aug. 15, greeted by a jubilant crowd of 80,000 and a Broadway parade in honor of the “Nation’s Guest.”

At age 67, far removed from the teenager who volunteered for the American cause of freedom almost a half-century earlier, the last surviving major general from the Revolutionary War received similar outpourings of affection as he visited all of the then 24 states. He attended balls and parades in his honor, visited battlefields where he fought, and reunited with former presidents and comrades from the Continental Army.

During Lafayette’s Philadelphia celebration in September 1824, he met Easton lawyer James Madison Porter, whose father had served with Lafayette at the Battle of Brandywine. From that encounter, Porter, one of the 200 delegates from Easton, would propose naming a college in the city in Lafayette’s honor.

Choosing items reflecting the Marquis de Lafayette’s euphoric return to the nation he helped free from monarchical rule, including those from the Easton delegation that met Lafayette, was no easy task. It required the eyes and instincts of someone like Luhrs to present a living storyline.

Many of the items in the College’s Marquis de Lafayette collection came from Stuart Wells Jackson, a leading Lafayette collector of his day, who founded the American Friends of Lafayette at Lafayette College in 1932. The organization is dedicated to the memory of the Marquis de Lafayette and devoted to the study of his life.

“I started by assessing the strengths of our collection, in terms of the farewell tour,” says Luhrs, who spent the summer examining the items in the Lafayette collection.

“My focus is on the materiality of the tour, which is what most of our memorabilia reflects,” she adds. “It’s a really great way to invite people to think about the people who don’t usually get featured in stories or exhibits such as this. I wanted to consider the everyday person. We’re celebrating the Marquis. But I was really interested in what the average person was thinking about in 1824-1825 when the Marquis was on his grand farewell tour. What were neighbors saying about this man?”

Over the summer, Luhrs offered a peek into her exhibit planning and her reactions to some of the items she selected. As she opened archival boxes and folders, you could almost see crowds line up for a parade in Lafayette’s honor, a 19th–century brass band play a ceremonial march in his honor, or hear clinking Champagne flutes at one of the many Lafayette balls held in cities across the nation.

Here’s a preview of the exhibit, highlighting some of Luhrs’ favorite items for each of the four sections of the exhibit.

A hero returns

The landing of Lafayette in New York on Aug. 15, 1824, is depicted on a ball invitation Luhrs pulled from the archives.

“This was the very first big reception that he received after his arrival in the U.S.,” Luhrs says. “He landed in Staten Island on Aug. 15, then took a steamboat from Staten Island to Castle Garden (now Battery Park) the next day. In Castle Garden is where you start seeing the fancy engraved invitations, with Lafayette’s image, to the Castle Garden ball. You’ll see this image in Staffordshire ceramic transfers. This is a really popular image for the tour.”

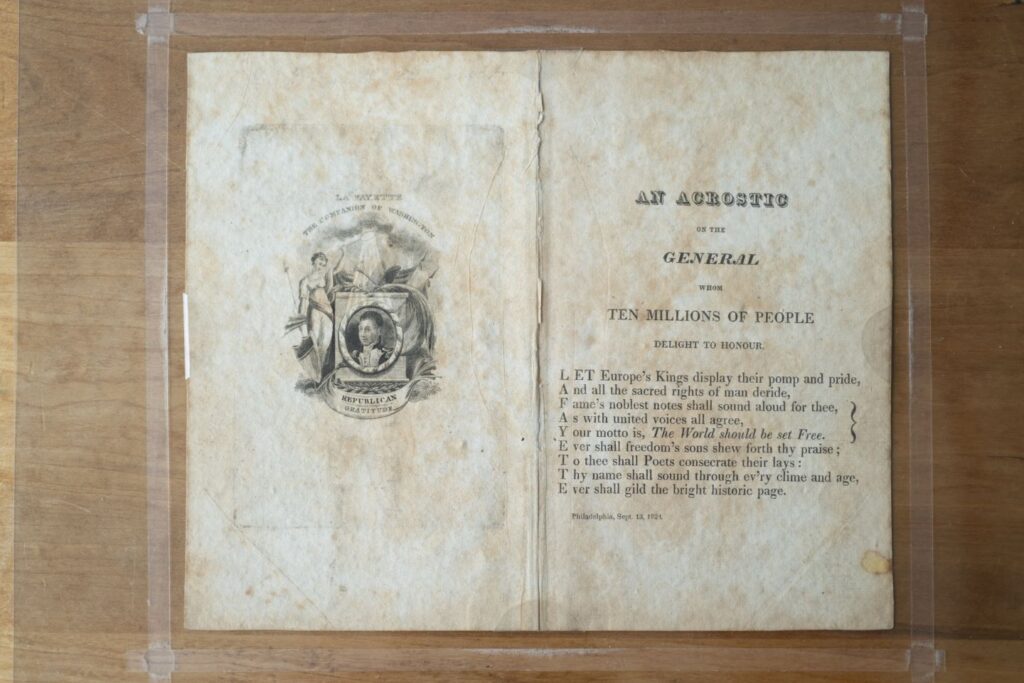

Acrostic poem written to welcome Lafayette | Photo by Adam Atkinson

She also admires an acrostic poem written to welcome Lafayette. On the panel opposite a depiction of Lafayette in his military uniform on age-yellowed paper, the poem reads:

L ET Europe’s Kings display their pomp and pride,

A nd all the sacred rights of man deride,

F ame’s noblest notes shall sound aloud for thee, ~

A s with united voices all agree,

Y our motto is, The World should be set Free.

‘E ver shall freedom’s on hew forth thy praise

T o thee shall Poets consecrate their lays

T hy name shall sound through ev’ry clime and age,

E ver shall gild the bright historic page.

Formal ladies’ kid gloves | Photo by Adam Atkinson

Balls and dinners

A pair of well-preserved long, formal ladies’ kid gloves with images of Lafayette catches Luhrs’ attention, as well as elaborate ball invitations from Charleston, S.C., which has a pillared Federal-style design, and another from Philadelphia, with its elaborate silk ribbon bearing the tricolors of the U.S. and France.

She chose an intricately decorated linen handkerchief, likely from a high society ball, depicting scenes of Lafayette’s visit to Independence Hall and his arrival in New York, and a decorative ceremonial German-made sword and scabbard worn by an unidentified member of the Easton delegation who attended Lafayette’s parade in Philadelphia.

Ceremonial sword carried by member of Easton delegation visiting Lafayette in Philadelphia | Photo by Adam Atkinson

The parades

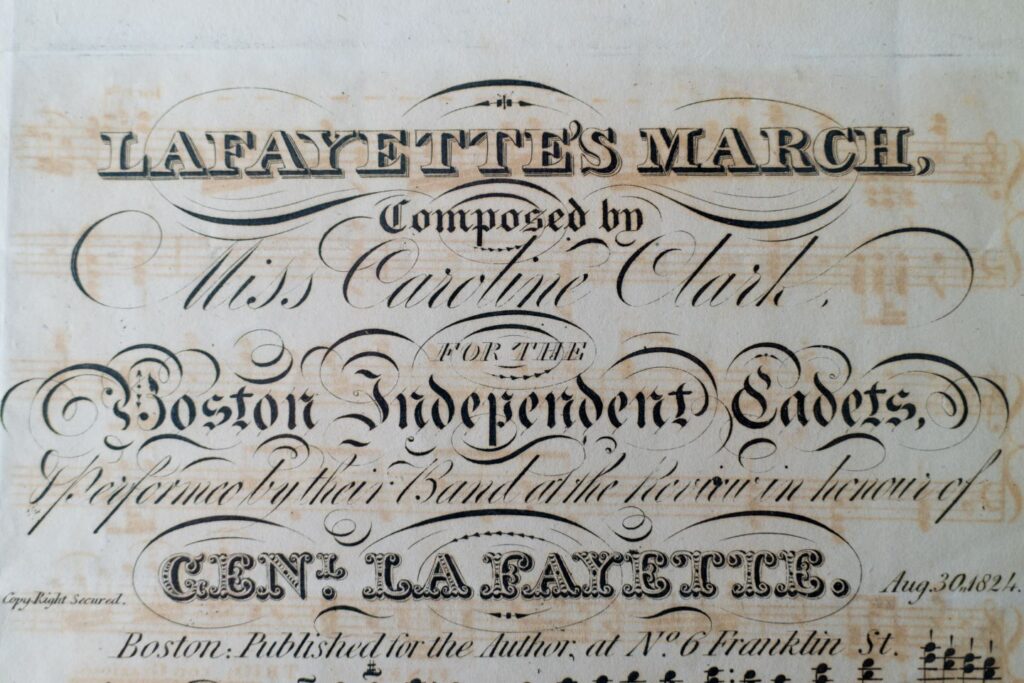

Brass bands became popular in the U.S. in the 19th century, and a copy of “Lafayette’s March,” elaborately typeset and composed by Caroline Clark for the Boston Independent Cadets, an elite Massachusetts militia unit, reimagines the grand civic parades held in Lafayette’s honor. The Andante tempo marking indicates a slow, stately march.

“Lafayette’s March” by Caroline Clark | Photo by Adam Atkinson

Keepsakes for the home

Personal mirror | Photo by Adam Atkinson

When Luhrs opened the box containing a pewter-framed personal mirror bearing a likeness of Lafayette, she could imagine someone just like her staring back from 1820s America. “It kind of gave me a chill,” she says, noting that, just like today, 19th–century Americans loved to collect merch to remember special events.

For the exhibit, she also pulled out an ebony snuff box, still issuing a sweet tobacco aroma, imprinted with Lafayette’s image.

Snuff box | Photo by Adam Atkinson

“I wanted this exhibit to not only capture the overwhelming displays of love for Lafayette during his Grand Tour but also about the whole country during this specific time period,” says Luhrs, describing the upbeat mood in the U.S. during Lafayette’s visit as the nation prepared for its 50th anniversary.

“They call it the feel-good era, where people were optimistic about where the country was headed,” she adds. “With Lafayette’s visit, America was reliving, in a way, The Spirit of ’76.”

2 Comments

What are the hours to view the exhibit? Will there be weekend hours? Thank you.

The gallery is open Wed-Sun 12-5 p.m.

Comments are closed.