Lafayette geology rocks with outdoor classroom

By Bryan Hay

In warmer weather, and beneath the canopy of the katsura tree on the south side of Van Wickle Hall, geology and geosciences faculty and their students gathered on a blue stone terrace with comfortable tables and chairs, an outdoor video monitor, slate chalkboard, and rock gardens.

Welcome to the Department of Geology and Environmental Geosciences’ outdoor classroom. During the fall semester, this space quickly became a natural gathering area for students seeking a serene setting to study and relax, and a perfect learning environment for students studying and appreciating geology.

Video by Olivia Giralico

On a fall day, David Sunderlin, John H. Markle Professor of Geology and department head, met casually with students gathered at the outdoor classroom to hear their reaction to it.

Studying geology is all about being outdoors, and Sunderlin credited his creative colleagues for pursuing and developing the outdoor classroom idea with generous support from Dr. Charles E. Bartberger ’67 and his wife Gretchen Platt.

“Geology is the study of a lot of outdoor phenomena, so we may as well be outside, experiencing it,” he says, enthusiastically pointing out the many interesting features of the outdoor classroom.

These include the stunning retaining wall made of dolomite, the 500-million-year-old Cambrian bedrock beneath campus; exotic and Pennsylvania rock and gravel gardens on the north and east side, respectively, of Van Wickle Hall; rock samples around the interior edges of the terrace to demonstrate the phenomena of folding and help students prepare for detailed field lab experiences; the chalkboard made from locally quarried slate; the weatherproof video monitor; and right down to the teachable blue stone steps that on close inspection reveal the grain and layering of the rock, which helps geologists interpret the history of where and how it was originally deposited, not to mention the colorful petrified wood samples and red-studded Adirondack garnet ore in the exotic rock garden.

Slate chalkboard and weatherprrof monitor. | Photo by Adam Atkinson

“It’s not a very common thing to see on a college campus, an outdoor classroom that’s quite as extensive and geologically themed as this one,” says Sunderlin, noting that Lafayette currently has about 50 geology majors an minors. “To be able to have a place that can serve as an outdoor academic space but also a place where you can have a leisurely lunch while being surrounded by all of these wonderful geologic references really captures the spirit of Lafayette.”

Retaining wall made of dolomite | Photo by Adam Atkinson

Geology class rocks

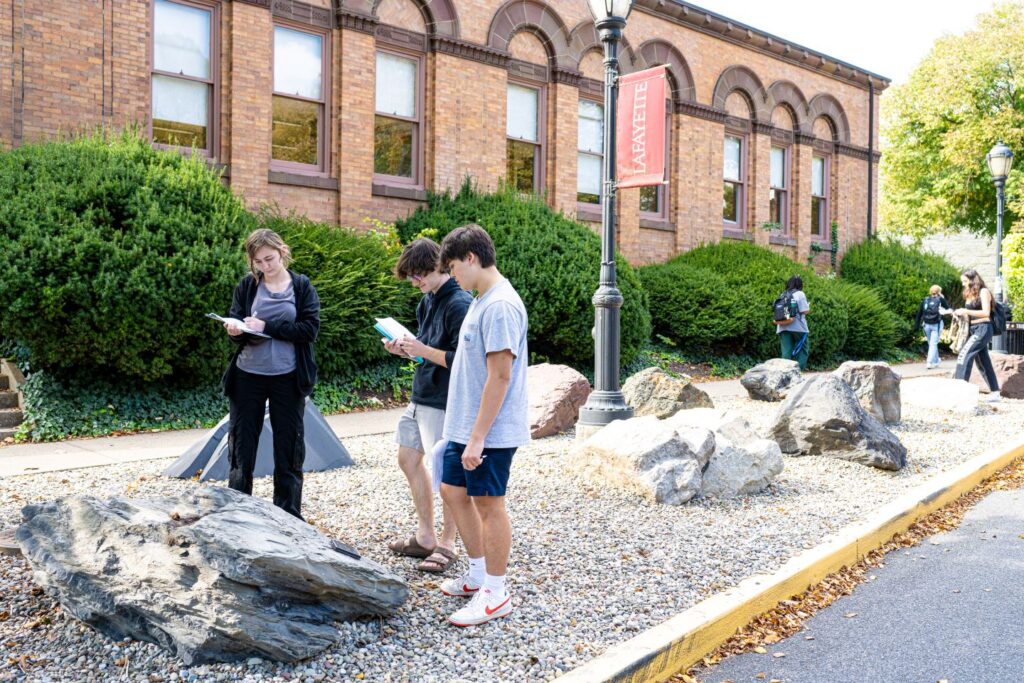

Later the same day, Lawrence Malinconico, associate professor of geology/geophysics, assisted by John Wilson, laboratory coordinator, gathers students on the terrace for a geology-oriented scavenger hunt across campus as part of his GEOL 120: An Introduction to Geology: Geological Disasters class.

The objective was to identify the various exposed rock found in Lafayette’s buildings and structures, including Pardee Hall, Kirby Hall of Civil Rights, Hogg Hall, Farinon College Center, and the exterior pillars of Markle Hall. Students grabbed their note sheets and vials of hydrochloric acid to test for the presence of the mineral calcite in the rock garden samples.

Jack Holinstat ’27 tests for the presence of calcite in the rock garden samples. | Photo by Adam Atkinson

“Don’t use the acid on any of the buildings, only on the rock samples,” Malinconico says with a cautionary smile. Everyone soon learns that most of the iconic buildings on campus were built using coquina, a pale-colored sedimentary limestone made up of fragments of shells, corals, and other marine invertebrates cemented together 300 million years ago.

“Rocks tell stories,” says Wilson, beaming as students start to discover a deeper appreciation of geology and how rocks provide a foundation for the history of Earth and chronicle the progress of humankind.

“When you start looking at this with a geologist’s eye, you start to take notice of those shell fragments as they pop out on campus,” he says. “It tells us that the columns holding up the front of Markle Hall were once an ancient beach sea environment. The blocks that make up Colton Chapel and exterior of Kirby Hall are a similar style material. You can see all the little fossil shell fragments. Having this outdoor classroom is a perfect environment for this kind of discovery.”

The Pennsylvania rock garden. | Photo by Adam Atkinson

Taking a break from the scavenger hunt, Marin Rosser ’27, a geology major with a concentration in environmental geosciences and a minor in environmental science, says the outdoor classroom enhances the Lafayette experience. An ROTC cadet, she hopes to fly helicopters for the Army and afterward pursue a career as a geological or environmental consultant.

“It’s really awesome to have this. It’s a more natural way to learn about rocks and the natural environment. We’re doing our lab today, and it’s all about rocks. We’re finding these rocks in the classroom itself, and we find them around campus. Being outdoors really immerses us in this learning experience. With the rock gardens, you see a sample of granite and then realize that it’s on your countertop at home. This is so enticing to people who are interested in the natural world and maybe don’t know a lot about how it influences our daily lives.”

Josh Freiheiter ’27, a government and law major, says the outdoor classroom was an inviting way for him to explore his interests in geology.

“Some of the observational skills from my gov law classes coincide with this geology class as well,” he observes. “This outdoor classroom is really neat. I’m big into outdoor things, and I’m a visual learner. Having this outdoor classroom helps improve observational skills, and now I’m getting a chance to learn more about the different rocks and formations around campus.”

Geology, ecumenical, foundational, everywhere

The outdoor classroom is part of the Department of Geology and Environmental Geosciences’ outreach, Malinconico says.

“One of the big things that we’ve done in the department is try to show people who we are and what we do,” he says. “By having the rock gardens on the east and north sides, and this facility on the south side, it’s one more thing for people to ask, What’s going on in that building? What are they doing in there?

“The more people who walk by and say, ‘I should take a class in there,’ the more potential students we will have who find that geology is something that they’re excited about and how geology is relevant to so many disciplines,” Malinconico says.

“We really are the ecumenical science,” he adds, noting that geology requires foundations in mathematics, chemistry, and physics, and intersects with civil engineering, government and law, policy studies, and even the humanities and social sciences.

Lawrence Malinconico, associate professor of geology/geophysics, leads an outdoor class. | Photo by Adam Atkinson

He says the majority of Lafayette’s geology grads over the last several decades have found successful careers in environmental consulting. Others’ career paths include working with government agencies, real estate law, or earning a Ph.D. and landing a career in academia.

A garden of rocky delights

Donated by local and regional quarries, masonries, building material companies, and other sources, the 16 boulders that populate the Pennsylvania rock garden require more than a cursory glance.

They tell a story, and Wilson, who loaded each rock in his pickup truck and relied on Jeff Weed, supervisor of grounds, and his crew to place them, is eager to share it.

The rocks range from the oldest, billion-year-old Baltimore and Byram gneiss, composed of quartz, feldspar, and mica, to the most youthful garden occupant, a 200-million-year-old iron-rich diabase rock from the early Jurassic period. In between they trace the depositional history of sediments and the resulting diversity of rock types in the eastern Pennsylvania region.

What’s more, the Delaware River gravel on the garden bed is more than decorative and functional material. “It includes all of the rocks in the Pennsylvania garden,” Wilson says.

John Wilson, laboratory coordinator, at the chalkboard made from locally quarried slate. | Photo by Adam Atkinson

“Rocks are teachers,” he says. “That’s the beauty of geology. There are so many stories to tell, and we hope the addition of the outdoor classroom provides an ideal setting to share and learn from the stories that only come from rocks.”