Finding a resource in what remains

By Margaret Wilson

On farms around the country, phosphorus-based fertilizers are being applied to fields to increase the productivity of crops. However, the primary method of acquiring phosphorus requires mining phosphate rock, a labor- and resource-intensive process that depletes a finite resource.

This summer, Katherine Twiggar ’28 hoped to find a more sustainable place to gather phosphorus: the tons of biosolids accumulating every day in our municipal wastewater treatment plants.

Working alongside Jennifer Rao, assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, Twiggar joined a team of student researchers to study the effects of phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria to separate the valuable element from a material that is usually consigned to a landfill.

“Phosphorus is a finite resource, and eventually it’ll run out,” Rao says. “We apply it as fertilizer, we eat it, and it ends up in these biosolids. It gets run off into waterways, and we lose it. We’re not reclaiming it well. So if there’s a way that we could actually reclaim the phosphorus out of these biosolids before they get sent to a landfill, that could be a way of getting the phosphorus back.”

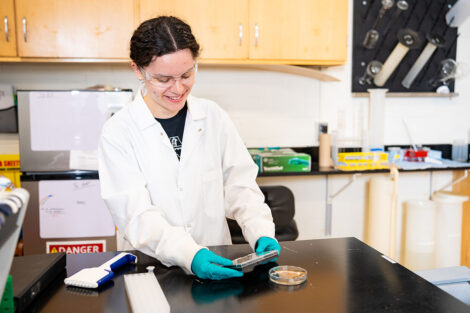

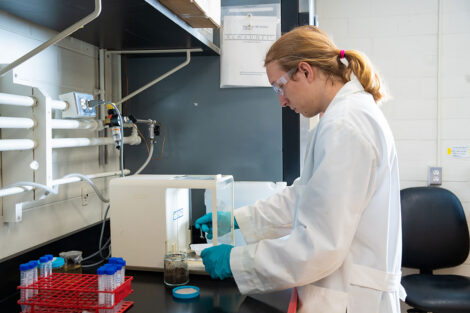

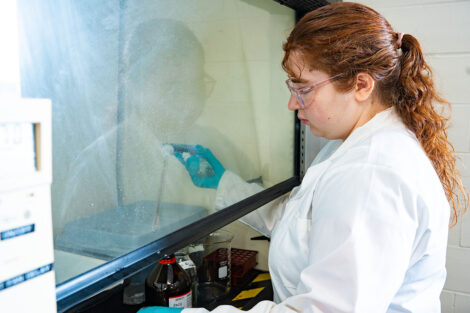

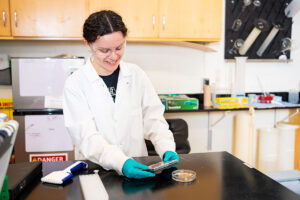

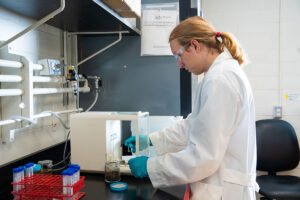

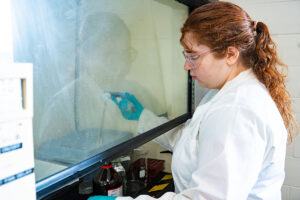

Twiggar, a Clare Booth Luce and Ally Research Scholar [CBL], joined fellow CBL Scholar Emma Martin ’28, as well as Owen Burry ’27 and Regan Thompson ’27 in Rao’s summer lab. Twiggar and her teammates collected biosolids from the Easton Wastewater Treatment Plant and brought them back to campus to test out the efficacy of various bacteria to isolate the phosphorus.

“It’s all soil bacteria, so it’s just what is found in nature,” Twiggar says. “This is a process that’s trying to alleviate some environmental strain, so using natural bacteria from the ground is important.”

While Twiggar has focused on removing the phosphorus, other students in Rao’s lab worked on the solids left behind. By adding an extraction solvent, they aimed to turn the remaining waste into a polymer that can be used to make plastic, taking one step closer to a closed loop system.

While this is the first year Rao has run the lab, it’s not the first time it’s been studied on campus. Rao inherited this work from Art Kney, professor emeritus of civil and environmental engineering, who retired in the spring. Kney also worked on the project with Joseph Colosi, professor emeritus of biology at DeSales University.

“He and I worked together a lot over the years, and when I was in graduate school I adjunct taught [at Lafayette] with him,” Rao says. “When I came on board to the College, he asked if I wanted to get involved.”

An integrative bioengineering and international studies double major, Twiggar started out volunteering in Rao’s lab the spring of her first year, hoping to expand her horizons in bioengineering.

“In the spring of my freshman year, I was looking for ways to get involved in research. I’m not really sure what I want to do after college, so research felt like a good way to see this avenue of research and graduate school,” Twiggar says. “So I reached out to my adviser, who gave me a list of professors doing research in bioengineering.”

Prof. Jennifer Rao (left) and Katherine Twiggar ’28 (right) have worked closely together during Twiggar’s time as a CBL Scholar. | Photo by JaQuan Alston

Her experience volunteering led her to pursue the CBL program to more fully engage in the research over the summer, a process that brought her even more than a lab position. The program seeks to advance a community of women engineers and allies.

“CBL funds engineers in all fields, and they have weekly lunch talks, so it’s been really interesting to learn about the different aspects of research,” Twiggar says. “All of us come together to these talks and learn about research posters or careers, and get to talk with other people in other labs about how they’re doing it.”

For Rao, the ability to include first-year students in her lab is part of the uniqueness of the Lafayette experience.

“I think it’s great, starting that early. I wish I had when I was an undergraduate, but there weren’t as many opportunities because I went to a school that had a graduate school,” she says. “That’s why I love Lafayette, because the undergrads get to do the work. At a big research institution, undergraduates can maybe do the grunt work. I liked Lafayette because of the undergraduate attention and the focus on teaching.”

“I don’t know if I would have had this opportunity, at the level of involvement I’ve had, at other schools,” Twiggar says. “Professor Rao and I will meet and talk about what we want to do next week or in the future. My opinion matters, and it’s definitely encouraging.”

Rao will continue work on this project throughout the year, with Twiggar joining her lab again in the fall to keep working on optimizing the bacteria’s solubilization. One day, Rao hopes they can pilot their findings on a large scale.

“I would love to get to a point where we could build a pilot scale reactor at the [Easton] wastewater treatment plant,” she says. “We could work with LaFarm to see how we can turn that phosphorus into something we can use. The more we demonstrate these things on a small scale, then you can actually scale it up to a more industrial size.”

Twiggar is looking forward to taking advantage of everything Lafayette has to offer, including a semester abroad in Germany as part of her international studies major.

“I think that’s why I like [the idea of] doing research, going abroad, doing internships,” she says. “I really look forward to learning more about myself, and how I connect with different things.”