Prof. Suzanne Westfall fills in the gaps of English drama in the Age of Shakespeare

When most of the modern world considers the age of Shakespeare, it thinks of William Shakespeare – perhaps the greatest playwright of all time – and then, well, the others, whomever they may be. Even Ben Jonson, a renowned playwright himself, said of his contemporary, “He [Shakespeare] was not of an age, but for all time.”

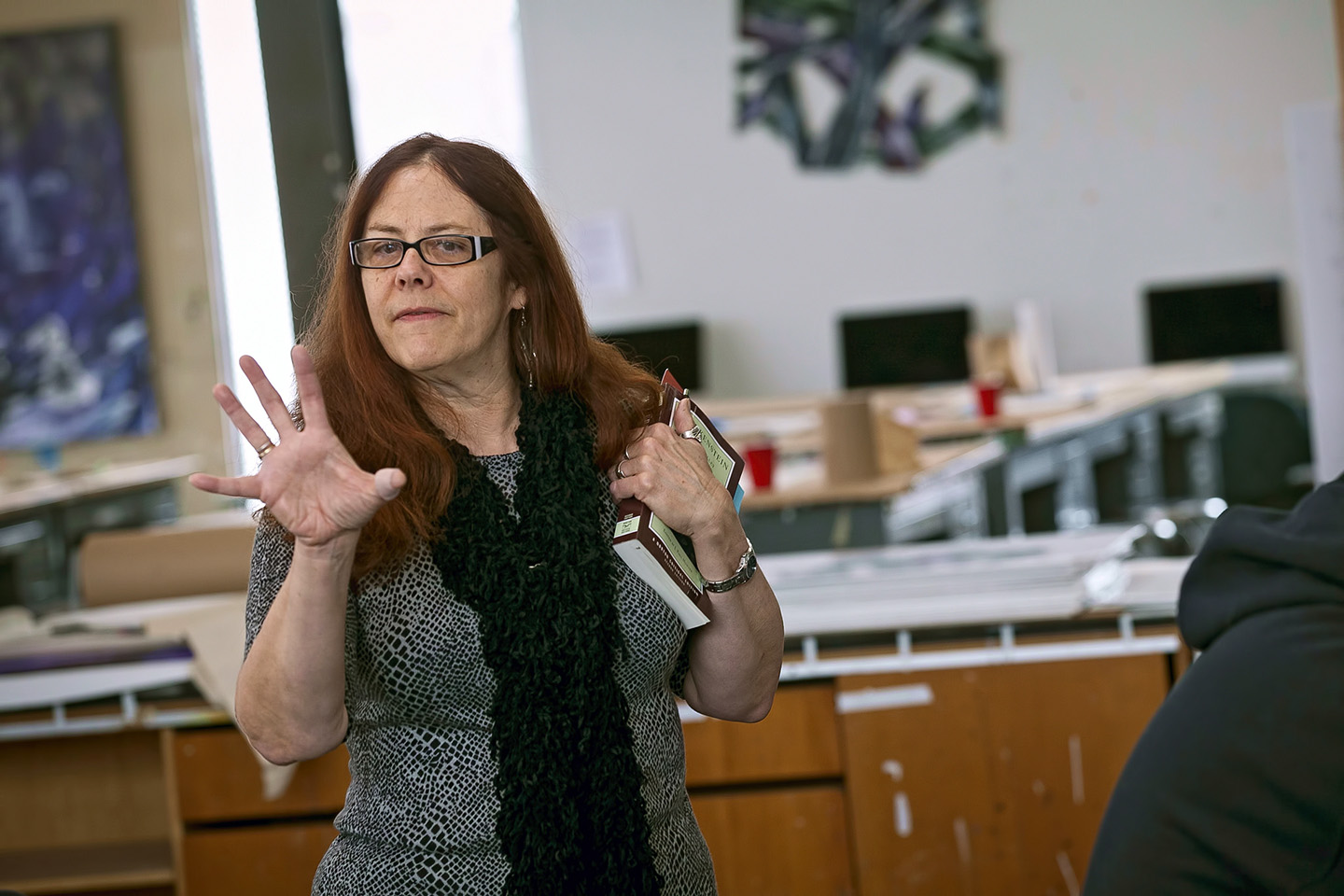

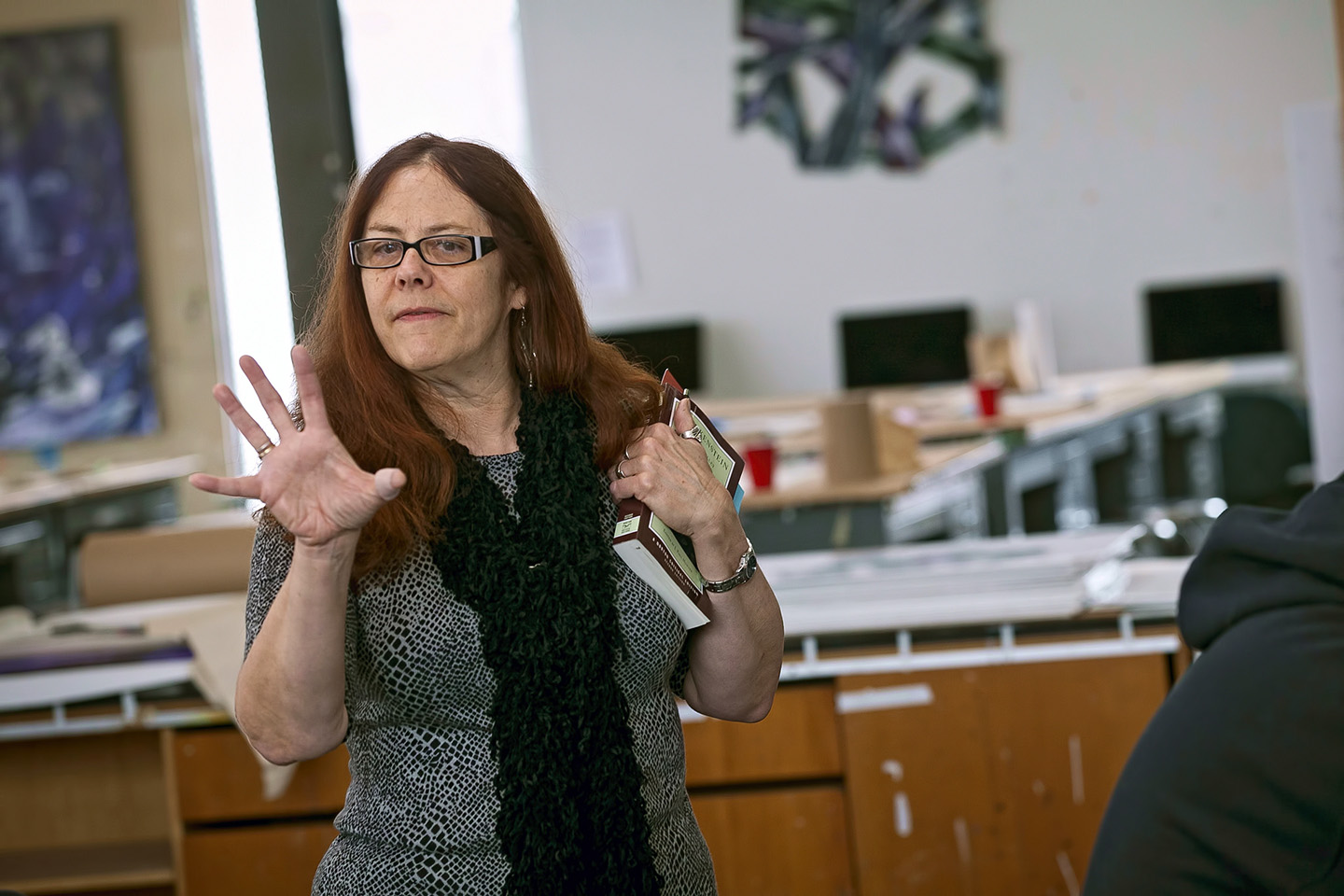

Suzanne Westfall

But to think of Shakespeare as a creative genius who scribbled out the world’s greatest works in a vacuum is a mistake, says Suzanne Westfall, professor of English/theater. There was an explosion of dramatic performance pieces that were created by, until now, largely unknown writers living in the Bard’s formidable shadow.

Westfall is part of the Records of Early English Drama (REED) project, for which she has received a National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) grant. The grant is helping fund her canvas of the shire of Northumberland for all references to performances in England from the earliest she can find to 1642, the year Parliament shut down the theaters under pressure from the Puritans who morally opposed them.

“The REED project has completely changed the way scholars understand theater in the so-called ‘age of Shakespeare,’ opening our studies to new writers and new venues, while widening the scope of theater from urban and London-based bardolatry to an expansive network of sophisticated performance all over the country,” explains Westfall, who will travel to Berwick-on-Tweed and Newcastle this summer for more research.

Suzanne Westfall

Over the last 35 years, the REED project has published 24 hardcover volumes, with Westfall’s work on Northumberland to be published in the final volume. The project also has contributed to several open access free websites, including the BBC’s celebration of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. It is an enormous undertaking, but one that is well worth it, says Westfall, who calls REED’s discoveries “revolutionary.”

The New Oxford Shakespeare put out this year by Oxford University Press and edited by an international team of scholars led by Gary Taylor, reveals Shakespeare as a great collaborator and gives recognition to the other playwrights with whom he worked.

“REED has taught us that theater was a collaborative art, with many hands in the process, and that theater was about performance, not just about texts to be analyzed by literary critics,” says Westfall.

In a way, Westfall is playing a role as well – that of literary detective. While she says there may not often be texts or descriptions of the period’s entertainment, there almost always are financial records that allow scholars to reconstruct how people celebrated with theater, music, and dance. She expects to spend a few more years tracking civic, ecclesiastical, and private accounts of theatrical performances from that period.

Westfall often uses REED records to introduce her students to primary sources so that they can engage with the words and thoughts of people “long dead who were as vibrant and exuberant as we are.” For instance, REED uncovered the trial of Sir John Yorke who was accused of producing a “Catholic King Lear” by Richard Cholmeley, a Yorkshire recusant, around 1605. “Treason, sort of,” explains Westfall of a time when the Church of England was the law of the land.

“Even through political and religious upheaval, when the powers that be tried to kill the theater, people found ways to celebrate their lives with music, laughter, tears, and revelry,” she says. “It’s a celebration of life and the creative spirit, which is as necessary in today’s terrifying world as it was through plague, wars, bigotry, and economic strife so many centuries ago.”

For all time, indeed.