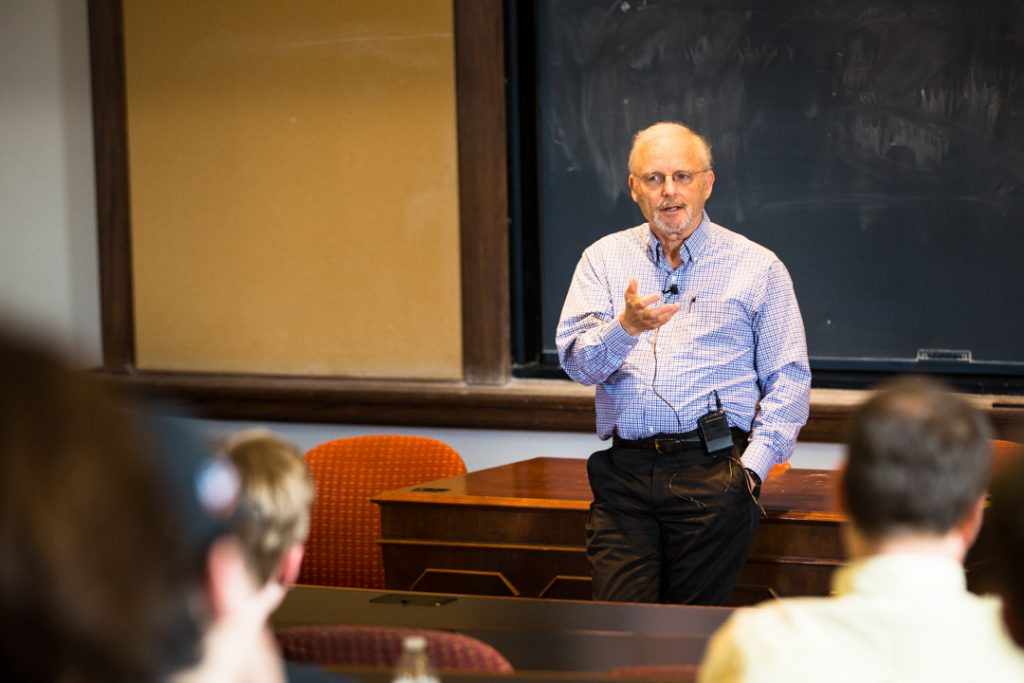

Best-selling author and renowned nature advocate Richard Louv speaks about the value of outdoor experiences.

By Katie Neitz

By Katie Neitz

There is a way to boost creativity, reduce stress, and enhance your overall health and well-being. It might sound like a too-good-to-be-true miracle drug. But it’s not. It’s as simple as going outside.

Renowned author and nature advocate Richard Louv spoke on campus recently about the tremendous value of spending time outdoors, and the ill effects kids, adults, and society can suffer if such experiences are neglected. Louv’s lecture was part of the College’s Interdisciplinary Seminars in the Life Sciences speaker series, organized by Assistant Professor of Biology Mike Butler.

When Louv wrote Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder (2005), the positive impact of nature on physical and mental health was more anecdotal than evidential. The book became a celebrated best-seller, making “nature deficit disorder” part of the national dialogue, especially among parents, educators, and researchers.

Today, thanks to Louv’s influence, there is a substantial body of evidence that proves nature does the body and psyche good, and negative consequences (obesity, attention disorders, and depression) arise when screen time overrules outdoor time.

“I had imagined this movement—this movement to turn this ship around, to get children out in nature,” Louv told the audience of more than 70 students, faculty, and community members. “It was wishful thinking at the time. But that movement has emerged. People are understanding the importance of connecting to the natural world. We now have studies that show that cognitive development and functioning goes up when you learn in a natural environment. By ‘greening’ a school—creating a natural learning environment with gardens and experiences in nature and animals and plants in the classroom—we are seeing kids doing far better on standardized tests.”

Indeed, Louv’s passion project has sparked a cultural shift. At the grass-roots level, Louv has encouraged the development of regional “family nature clubs,” networks of people who have formed communities that gather for group outings. Louv’s local family nature club in San Diego, for example, is comprised of 2,000 families. And at the federal level, he cited the “Every Kid in a Park” campaign, which enables fourth-graders and their families free entry into the country’s national parks—recognition that kids (and their parents) benefit from exploring nature’s playgrounds.

While Louv is pleased with the progress made as evidenced by such programs, he said more work is needed, especially as society becomes increasingly plugged in. “The more high-tech we become, the more nature we need,” he said.

And so, Louv has continued his advocacy via The Nature Principle: Human Restoration and the End of Nature-Deficit Disorder (2011) and Vitamin N: The Essential Guide to a Nature-Rich Life (2016). His books have been translated into 13 languages and published in 17 countries. His next book will focus on the importance of developing stronger bonds with the animal world.

Through his writing and his speaking, Louv aims to inspire (current and future) educators, health professionals, parents, developers, and conservationists to take action—starting right in their own backyards—to embrace the transformative and restorative powers of nature. Not only will doing so help us build better communities and economies, he said, but it will enhance our own health and well-being, and relationships with those around us.

Here are five actionable takeaways from Louv’s lecture:

“If you ask Americans to conjure up images in their mind about the far future, the images that come up are almost always of something that could be from a post-apocalyptic movie,” he said. “We are raising kids in a culture that is telling them that it’s too late, that the damage is done. And we carry that around with us. Instead, we want students to see hope in the movement. ” He said that he believes a shift needs to be made in how we approach and talk about environmentalism so future generations can see that they can still make a positive impact on the world.

- Help Diversify the Field …

“The big environmental organizations are not diverse,” Louv said. “The membership is like me—old, white guys. They are aware of this, and they are trying to make changes. I’m hoping that continues. We need kids from all backgrounds to want to be environmentalists.”

“I like to talk about ‘nature-rich’ schools and homes and neighborhoods and cities, so you start to see native species come back, and start to feed the food chain,” he said. “I believe that citizens can become engines of biodiversity. My wife and I changed our backyard to native species, and all of a sudden we are seeing California-native butterflies and bees and lizards. Why is it we see ourselves alone on the planet so much? Why do we see it as just our yard? What if it was the next yard and the next yard and the next yard, so that suddenly we had wildlife corridors going through our cities. You’d have insects, and birds, and the whole chain. And what if it went from city to city. We could have worldwide homegrown parks. Why are we waiting for governments to do this?”

- Connect with Other Species

“I believe we need to focus on animals and the relationship we have with them,” he said. “I don’t think we focus on our relationships with other creatures enough and the fact that there is something between us—not just companion animals but also wild animals. Why is it that we only talk about one species? I think we need to live in symbiosis with other life, and that we need to approach our future that way—even in the densest of neighborhoods. Why is it that the urban parks with the highest biodiversity have the highest impact on human health? Because you are not alone. We need other life. We need other creatures. We need a new relationship with nature that’s not only about people.”

“We are creating environments in schools and houses and cities that are focused on technology and screens,” he said. “When you are looking at screens, you are working to cut out other senses in order for you to focus on the screen. If a child grows up sitting on the couch playing video games, certain special senses that are developed when out in the natural world atrophy. Ideal students have two sets of skills—they can use technology, but they can also function in the real world with full senses. They know the world via virtual reality and real experiences. I think that should be the focus: to develop the hybrid minds of the future.”

The next Interdisciplinary Seminars in the Life Sciences speaker will be Jen Owen, who will speak Monday, March 26, at noon in the Kirby Hall of Civil Rights auditorium, room 104. Owen works in the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife and Department of Large Animal Clinic Sciences at Michigan State University.

By Katie Neitz

By Katie Neitz