By Kathleen Parrish

Ever wonder how certain speakers find their way to campus? In LGBT activist and author Rita Mae Brown’s case, it was Cosmopolitan magazine via Dr. Catherine Hanlon ’79.

In 1999, Hanlon, an emergency room physician and former flight surgeon with the U.S. Air Force, was featured in Cosmo’s Fun, Fearless, Females section, where she quoted a character from Brown’s 1973 novel, Rubyfruit Jungle, now regarded as a classic in lesbian literature. Hanlon later realized she forgot to credit the author, an oversight at odds with her Lafayette education, so a few months later she cut out the article and mailed it to Brown with a letter of apology. The gesture elicited a phone call four months later from Brown.

“I guess if you can fly jets you can ride a horse,” Brown said. “Why don’t you come down to Charlottesville (Va.) for a fox hunt?” An extreme sports junkie, Hanlon scuba dives, skis, and kayaks and has served as a physician to wilderness expeditions, including treks to the Amazon, Antarctica, and Sea of Cortez. But horseback riding was never her thing.

“I guess if you can fly jets you can ride a horse,” Brown said. “Why don’t you come down to Charlottesville (Va.) for a fox hunt?” An extreme sports junkie, Hanlon scuba dives, skis, and kayaks and has served as a physician to wilderness expeditions, including treks to the Amazon, Antarctica, and Sea of Cortez. But horseback riding was never her thing.

Regardless, she accepted the invitation, and the two women have been friends for 20 years. “We just hit it off,” says Hanlon, who earned a degree in biology at Lafayette and a white coat from Hahnemann Medical School in Philadelphia in 1983. “She has an absolutely irreverent sense of humor as I do.”

Author of 60 books (including murder mysteries with her cat, Sneaky Pie, named as co-author) and an Emmy-nominated screenwriter, Brown put her unvarnished candor on display during a Q&A prior to her talk in Colton Chapel last week, where she spoke as part of the Voices of Resistance Series, sponsored by women’s and gender studies, Friends of Skillman Library, the Queer Archives Project, and the English department.

What shift have you seen in attitudes toward queer-identified people?

Well, they’re not getting beat up in the streets. You used to see a lot of violence toward people who were identifiable. Particularly in feminine men—well, there still is, but no one ever said they were gay in college because in those days you often signed a contract, especially in state schools. There was a morals clause; you’d be thrown out for it.

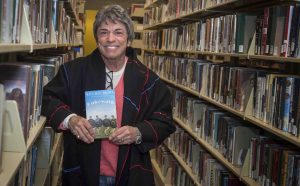

Rita Mae Brown and Diane Shaw, College archivist and director of Special Collections

One of the people who helped was Liz Smith, the gossip columnist. I met her (in the late 1960s) when she was in her early 40s. I said, “Liz, you’re the only person who can change this. You know everyone, and you’re funny, and you get paid a million dollars a year to blab on TV. Say something (about being bisexual).” She’d say, “No, that’s my private life, people don’t need to know.” This fight went on for years. Finally, she did come out, and it made a difference.

What are the challenges of today’s movement?

They’re asking for things impossible for this culture to deliver to anybody; they’re asking for their emotions to be understood. Hell, I don’t even understand my own emotions, and here you’ve got an 18-year-old or a 24-year-old all in an uproar that someone may have said something that was offensive to them or overlooked them. That’s not the way you get through life. The point isn’t that you’re the center of life, or what has been done to you is worse than what’s been done to anybody else. You want ugly? Go to Syria. You’re in pretty good shape, kiddo.

Rita Mae Brown (right) and Mary Armstrong, head of women’s and gender studies

So what advice would you give to the LGBTQ movement?

Shut up and humble yourself and start talking to other Americans. Really talk. Listen. Even if they’re saying things that offend you. It comes from somewhere. People just don’t get up and say, “I want to hurt a gay person this morning.” Maybe a few nutcases do, but that’s not the way we do things. Talk to them. Maybe they have good reasons or maybe they don’t, but maybe you just sitting and listening will break down that wall.

There’s been a lot of controversy lately over free speech on college campuses. Do you think freedom of expression should be limited so as not to offend certain people?

When I was young, I got beat up for speaking, and now I see the reverse of this. Why would I ever shut anyone else up? I don’t have to like what you say, but I have to listen, and number two, I want to know who my enemies are. I want to hear what they have to say. Maybe they can sharpen me. It’s like a whetstone; let me hear you, let me see you, because if we don’t know who our enemies are, when there’s a crisis, we’re going to find out in the worst possible way.

You once said your sexuality is the least interesting thing about you. Do you ever wish people just thought Rubyfruit Jungle was a great book instead of a seminal tale about being a lesbian?

You once said your sexuality is the least interesting thing about you. Do you ever wish people just thought Rubyfruit Jungle was a great book instead of a seminal tale about being a lesbian?

Yeah, it occurs to me all the time, because I think it’s this ghettoization of literature. If you walk into a bookstore there’s black literature, women’s literature, gay literature. Every story is a real story. To me diversity is up here [she points to her brain]. Do you really think white men have easy lives? Do you think every white man ever born has had an easy life and a silver spoon in his mouth? They get the shit kicked out of them. And every young man is a potential sexual predator? This is crazy stuff.

How did you get into writing mystery novels?

I was working in Hollywood in 1988, and it was great. I was doing very well, and I had my first Emmy nomination, and then the writers went on strike, which means nobody could work. So I’m sitting there and the bills kept coming in, and they’re big bills. I mean, you can’t live cheaply in Los Angeles. And I thought, “What am I going to do,” and I’d had books on The New York Times best-seller list, which doesn’t really make you the money like Hollywood did. Hollywood is like high school, only with money, and I have this wonderful cat, and the cat’s looking at me and says, “Write mysteries where the cat is the star,” and I thought, “The suburbs of literature—I will never stoop to that.” Well, I stooped. And it was my publisher who didn’t want to do it. They paid me $30,000 or $40,000, which was a pittance compared to what I was making then, and the damned thing just took off, just like Rubyfruit Jungle. Nobody wanted to publish it, and we’re still doing them, but it saved me from being a literary snob, and it forced me to focus on plot. I’m a southerner. I can go off anecdotally all over the place. Thomas Wolfe (author of Look Homeward Angel) makes perfect sense to me. You can learn something new in every one of those mysteries, but you don’t have to.

How do the social movements of today compare to the protests of your generation?

How do the social movements of today compare to the protests of your generation?

What’s real power? It’s monetary policy. It’s money. Not just making money but controlling money. If you understand power and you throw red meat at the ones who should be educated whether they’re at Yale or Lafayette or the University of Virginia. “Yeah, let’s get rid of these confederate statues,” or someone leered at a woman—that’s so far away from power, they don’t understand it. They’re being manipulated.

When my generation challenged authority, we understood power. The Women’s March was impressive. They were fabulous. I was very proud of those half a million women who marched without one example of wrongdoing or violence. And then there’s the second one, March for Life, which was completely inclusive. But what was the message? They mobilized beautifully, but there was no clear political objective. You can’t just say, “We’re against violence against women.” But they didn’t even say that, they said everything; “We’re against racism,” “We’re against guns.” It was so many things—how could you possibly focus?

Have you ever thought of running for office?

I’ve thought of running from it. My one great-uncle was county commissioner in Maryland, and another was county commissioner in York, Pa. I was illegitimate so I couldn’t claim any of these things. Yorkers are really different, and I watched how things got done. I learned that the politics you see is just theater. What’s really happening is behind the scenes, and you get your fingers on those nerves. First you have to prove you can hurt someone. You don’t have to kill them, but hurt them. Show them you can make their life shit. Don’t go to their stores, don’t elect them, shame them in public. Show them you can do real damage. You’d be surprised how they get out of your way, but women won’t do that.

From left: Elaine Stomber ’89, associate college archivist; Rita Mae Brown; Diane Shaw, College archivist; and Dr. Catherine Hanlon ’79

You did with Betty Friedan, co-founder of the National Organization of Women, when she tried to distance the organization from lesbian issues in 1970.

She was a brilliant woman, she really was, but she was a bully, she was vain, and she loathed gay women. And I was just a kid. I was 22 and in college, and she looked at me one day and called me a redneck in front of everyone. I said, “Well, this redneck reads Greek and Latin. Do you do that, Betty?”

But what I did was I slowly leached away her support. I would go to the gay women undercover, which was half of NOW. They were all married and had children, but they were gay in essence. And I said, “You know, she’s going to turn on you sooner or later,” and they said, “Oh no, she’ll never do it,” and a year went by and she did. They finally walked out. She was stupid; she lost half her man- or woman power, and that’s when Betty began to go down, and Gloria Steinem came up because she didn’t care, and she was younger and brilliant. So was Betty, but Gloria is warm. She is a loving person if you’ve ever been around her. She’s a kind person. Betty was a bitch; she got things done but the way she treated

Rita Mae Brown and Elaine Stomber ’89, associate College archivist

gay women was horrible, it was vulgar.

But you persevered, and in 1971 NOW recognized lesbian rights as a “legitimate concern for feminism.”

I’ll tell you a little story of why I will never fail. I will die, but I will not fail. Failure is just feedback for success. No matter what happens to you, you can learn from it. When I was at NYU, I had nothing, I was living on $5 a week. I had my academic scholarship but nothing else. I would go to this bakery down on Second Avenue because I lived in the East Village, which was a real dump then. My rent was $30 a month. I would go to this bakery and get secondhand food. It was like toast, but you could eat it. Behind the counter were these two men, probably in their 40s. They were brothers, and they liked me because I was young and southern and stupid, and I would laugh and joke with them, and it was summer, and they had their sleeves rolled up and they gave me a day-old loaf of bread. I could live off that for a week. And I said, “Why do you have your Social Security numbers on your wrist?” And they told me. It made such an impact. They were nice men, and they enjoyed life, and they gave to me, they gave to a shiksa. They didn’t have to give me a thing, but they did because they knew I had nothing. I thought, “Boy, if they can find the way to reach out to people and find the good in life, I have nothing to complain about.” So when people start to complain and make excuses, I have no time for them.

“I guess if you can fly jets you can ride a horse,” Brown said. “Why don’t you come down to Charlottesville (Va.) for a fox hunt?” An extreme sports junkie,

“I guess if you can fly jets you can ride a horse,” Brown said. “Why don’t you come down to Charlottesville (Va.) for a fox hunt?” An extreme sports junkie,

You once said your sexuality is the least interesting thing about you. Do you ever wish people just thought Rubyfruit Jungle was a great book instead of a seminal tale about being a lesbian?

You once said your sexuality is the least interesting thing about you. Do you ever wish people just thought Rubyfruit Jungle was a great book instead of a seminal tale about being a lesbian?  How do the social movements of today compare to the protests of your generation?

How do the social movements of today compare to the protests of your generation?