Anna Eisenstein ’13 and Professor Andrea Smith

When an unexpected tip from the local historical society led Andrea Smith to research an old Easton community known locally as “Syrian Town,” she thought it was the perfect opportunity to allow students to dig into the past of the community surrounding their college home. Demolished as part of the city’s urban renewal project in the 1960s, the neighborhood was home to people of Lebanese, Italian, African American, German, and Irish descent.

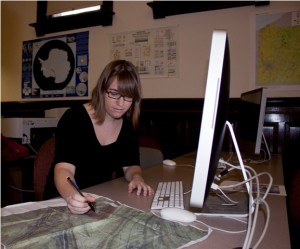

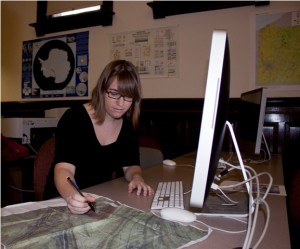

Anna Eisenstein ’13 (Patterson, N.Y.) and Kelsey Boyd ’11 (Lafayette, N.J.) joined the professor as EXCEL Scholars last year. Eisenstein is tracking down former residents to interview them about their memories of the neighborhood, while Boyd is using geographic information systems (GIS) mapping to determine what the neighborhood looked like before the demolition. Smith published an article on the research’s first phase, “The Language of ‘Blight’ and Easton’s ‘Lebanese Town’: Understanding a Neighborhood’s Loss to Urban Renewal,” in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography with Rachel Scarpato ’08.

Kelsey Boyd '11

“This neighborhood was unusually integrated for that time, but a kind of urban renewal fever was hitting the country,” explains Smith, associate professor of anthropology and sociology. “The City of Easton thought it would benefit the city overall to demolish this largely residential community. The plan was to bring in new luxury high-rise apartments and thus new wealth to compete with the burgeoning suburbs. This obviously didn’t transpire, and as a result of the pervasive housing discrimination at the time, the end result was increased ethnic and racial segregation.”

Eisenstein, a double major in anthropology & sociology and government & law, has found that former residents, many now in their 80s and 90s, are excited to share their memories. She’s discovered that one of the key clues to reconstructing the neighborhood’s identity is the language the former residents use when discussing the old neighborhood.

“I noticed an apparent contradiction in what they were communicating,” she says. “The large majority of our interviewees talked proudly about the neighborhood and how ‘integrated’ it was, yet the first way they described others was by their ethnicity. For example, ‘Now, Mrs. Salim, she was Lebanese, she…’ Some even mentioned certain areas of the city where certain ethnic groups were ‘allowed.’ We decided to delve deeper to see what might be causing these differing narratives to occur simultaneously.”

Many members of the Easton community are helping Eisenstein track down residents. Deacon Anthony Koury of Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Catholic Church, which was rebuilt in 1986 after the original structure was demolished in 1969, and Pastor Sue Ruggles of St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church have helped by linking the researchers with potential interviewees and providing space to conduct the interviews.

Boyd, a double major in geology and policy studies, is using her GIS know-how to create an overlay map on top of the historical map to show exactly how ethnically diverse the neighborhood was. Going house by house and block by block, she also is detailing the condition of the buildings at the time they were demolished. In all, the city removed nearly 800 homes.

For Boyd, this is truly an interdisciplinary endeavor. “I have enjoyed applying the mapping skills I learned in my geology classes to a different field of study,” she says.

Research in which the predominant data are people’s memories is an entirely different avenue of discovery from a textbook.

“Working with people who have been impacted by different renewal projects brings a whole new dimension to the classroom,” says Smith. “Students can study a recent historical trend, but when they talk to someone affected by that trend, it brings new meaning. Students will carry with them forever their interactions with these people. When students do on-the-ground research, the story always is a lot richer and more complicated than what they might get from a textbook.”