Notice of Online Archive

This page is no longer being updated and remains online for informational and historical purposes only. The information is accurate as of the last page update.

For questions about page contents, contact the Communications Division.

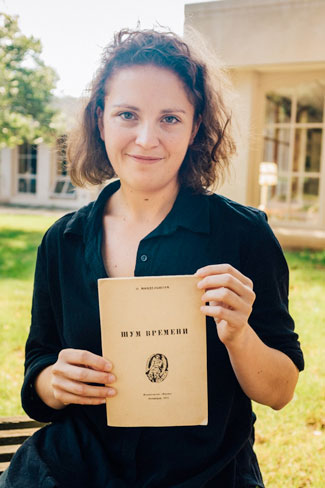

Assistant professor of Russian and East European studies

Ph.D., Slavic languages and literature, Princeton University

What I’m excited about:

“Teaching great literature and sharing it with students. Russian literature is the only philosophical tradition that Russia has known. These books generate unsolvable questions. We will always need them and we will always be talking about them.”

What I’m hopeful for:

“I’m hopeful that my colleagues and I in Russian and East European studies can generate even more interest in studying Russia, Central Asia, and East Central Europe. Relations between Russia and the United States grow more complex with each passing day. It is the study of Russian language, culture, history, art, and politics that can open up much-needed avenues of exchange and understanding in our present times.”

What I’m studying:

“I work on problems in intellectual and literary history during the late 19th/early 20th century in Russian culture, roughly between the deaths of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy (1881-1910). All of the figures I work on are philosopher-poets and religious thinkers with an interest in artistic creation, people working at a time of intense experimentation before the revolution. Many of their interests are offbeat and eclectic, and their erudition is staggering at times, so I have written on a range of topics from modern philosophies of death to occultism, genre theory and modernist theater to poetic form.”

What I’m holding:

“I’m holding a book, a collection of writings by the poet Osip Mandelstam. But it is the life and ideas in this book that matter to me. Mandelstam’s work captured me in college and nurtured in me a love of poetry and research. I still struggle to reconcile the two. His poetry finds ancient myth on urban streets and delights in the world of things. It sounds like music. In his autobiography he says that it isn’t where or who you come from, but when you live that matters. He writes, in Clarence Brown’s translation, “Where for happy generations the epic speaks in hexameters and chronicles I have merely the sign of the hiatus, and between me and the age there lies a pit, a moat, filled with clamorous time, the place where a family and reminiscences of a family ought to have been.”

Categorized in: New Faculty