By Kevin Gray

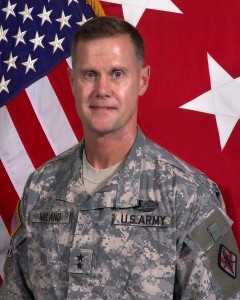

Major General James M. Milano ’79 assumed duty as the commanding general of the U.S. Army Training Center and Fort Jackson, S.C. on June 16. While the command position requires a great deal of strategic planning and operational oversight, Milano believes there is also a key requirement of the position that isn’t listed among his top responsibilities—visibility.

Major General James M. Milano '79

Milano often shows up unannounced at Fort Jackson training sites to speak with soldiers. He also makes regular visits in the community to meet with local business leaders or speak to high school students.

“I try to be out and about as much as I possibly can,” says Milano, who arrived at Fort Jackson — his third command post — after serving a year as deputy commander general of the Army’s 4th Infantry Division in Baghdad with oversight of the rebuilding of public utilities and services there. Before that, he was commanding general at Fort Knox, Ky.

“As a leader, I don’t want to be viewed as the great sage on the hill who only shows his face once or twice a year. I want to show the soldiers that someone other than their drill sergeant cares about them.”

The principal mission of Fort Jackson is to conduct basic combat training. The largest and most active Initial Entry Training Center in the U.S. Army, the fort provides basic training and advanced individual training to more than 50,000 individuals each year. That’s about 50 percent of all soldiers entering the Army annually. The fort includes about 52,000 acres, 1,160 buildings, and more than 3,900 active duty soldiers.

The military’s philosophy of training has changed over the years. Milano explains the Army has adapted basic combat training to better match what soldiers will do when they are deployed and how they will be fighting. For example, soldiers don’t execute the bayonet assault course that had been a staple in basic combat training in previous decades.

“The last bayonet assault that the United States Army was involved in was in Korea in 1951,” says Milano, who has served in Iraq, the Republic of Korea, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Germany, Kuwait, and many locations in the United States during his 31 years in the Army. “Training is much more functional and relevant than it used to be. We shoot a lot more now. We issue soldiers their weapons on their second day here, and the weapons are with the soldiers their entire 10 weeks. We also include more interaction designed to prepare solders to fight a thinking enemy.”

To incorporate this element of combat, training scenarios and simulations — often enhanced by the latest technology — are used. Command leaders also solicit opinions from the operational units that receive the soldiers.

“Seeking that information ensures that the soldiers receive training that is more relevant to their first units of assignment,” Milano says. “We have incorporated a lot of lessons learned into the training. Perhaps the biggest area of change in basic combat training is in physical readiness, which is much more in tune to the limitations of 18- to 20-year-old men and women.”

Physical readiness includes preparing new recruits for potential injuries that occur during training. Athletic trainers are assigned to training units and an Army-wide program called Fueling the Soldier is used to manage the quantity and types of food and drink offered.

Another area of focus during training is the mental rigors of combat. Soldiers are trained for psychological resiliency through physical toughness, emotional strength, social adeptness, and spirituality, among other aspects.

“We get young men and women from all walks of life and all different types of backgrounds,” Milano explains. “The incoming groups might include a farmer from Iowa, a gang member from Los Angeles, or a suburbanite from New Jersey, but we teach each of them what Army values are all about: loyalty, respect, duty, selfless service, honor, integrity and personal courage. No matter who they are or where they’re from, this is what we expect of them as soldiers in the United States Army.”

As the leader of this new breed of soldier, Milano not only believes strongly in visibility, but in vision as well. His vision for Fort Jackson includes making it the premier Army training center and an Army Community of Excellence (ACOE) Award winner.

Providing motivation as a leader comes, in part, from making personal connections. Milano says he learned the importance of building trusting relationships at Lafayette and has carried it with him throughout his military career. Even at the top levels of the military, these relationships start at the most basic levels. As Milano walks the fives minutes from home to office each day, he often encounters groups of soldiers.

“Interacting with them offers a real boost to their morale, and it absolutely energizes me,” Milano says. “I ask these new soldiers where they’re from and how they’re making out in basic training. You know, fewer than 1 percent of all Americans serve in the military, so I ask them why they joined the Army…then I thank them for doing so.”

Milano participated in ROTC at Lafayette, where he received a degree in chemical engineering. He trained at Fort Bragg and then went into the armor corps, becoming a tank commander in 1987. He served in Germany in the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment under Thomas E. White and John N. Abrams, who went on to become secretary of the Army and a four-star general, respectively.

Read an earlier story about Milano.