The National Science Foundation (NSF) has awarded Kira Lawrence, associate professor of geology, a $159,291 grant to expand her study of how a warm interval in the Earth’s past could be a predictor of the future of human-induced climate change.

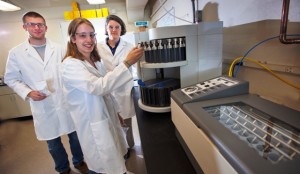

Chris Kelly ’13, Hollis Miller ’15, and Professor Kira Lawrence in Van Wickle Hall

“The record of Earth’s climate system we have from human observations such as measurements by thermometers, rain gauges, etc., is far too short to understand how this complex system will respond to the changes in the composition of the atmosphere human-activities have induced,” explains Lawrence. “The study of past warm climates, including the interval I study, the Pliocene, helps us understand how the system behaves when the global average temperature is warmer. Modern day atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations are approaching a concentration last seen during the Pliocene, so it represents an analog for the fairly near-term future.”

Lawrence uses the remnants of ocean organisms preserved in ocean sediments to reconstruct past changes in ocean surface temperature. While completing a synthesis of climate records from the Pliocene that she co-authored and published in a spring edition of Nature magazine, Lawrence realized that scientists do not have good spatial coverage of the Southern Hemisphere. The NSF grant will fund work at sites in the middle latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere to address the shortage of Pliocene datasets from that region and determine whether the Northern and Southern hemispheres responded similarly to post-Pliocene climate change.

The NSF grant also is supporting two student research assistants who are working with Lawrence through the EXCEL Scholars undergraduate research program. Hollis Miller ’15 (Fort Washington, Pa.), a double major in geology and anthropology & sociology, has been working in Lawrence’s lab since the spring semester. Geology major Rachel Griffiths ’14 (Dalton, Pa.) joined the lab this fall. They are preparing sediment samples for organic geochemical analyses, performed in Lawrence’s lab on campus, and stable isotope analyses, to be performed at Brown University where Lawrence earned her Ph.D. Miller and Griffiths also will help analyze and interpret data from the geochemical testing.

Lawrence frequently invites students into her research, giving them the opportunity to find out what real scientific inquiry is all about: “Students get to confront some of the challenges but also feel the exhilaration associated with discovering something no one else knows. Every student’s college experience ought to entail opportunities to see the world through new eyes,” she says.

The lessons learned from the Pliocene are “sobering,” says Lawrence. For example, geologic data from the period suggests that the Greenland ice sheet, which holds about seven meters or 23 feet of sea level equivalent, is very likely unstable under present atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations, meaning that over the long-term, there will be a substantial rise in sea level – a noteworthy finding given that a significant portion of the world’s population lives within seven meters of present-day sea level.

The Nature paper, Lawrence explains, demonstrates that even though the Pliocene was similar to modern in most respects, the spatial distribution of temperature was strikingly different. This suggests that modest changes in forcing, like the carbon dioxide change human activities have induced since the Industrial Revolution, could potentially result in a major shift in climate patterns, resulting in changes in temperature and precipitation regimes regionally. This kind of change could have significant adverse consequences for human populations because food and water sources are dependent on past, predictable patterns of temperature and rainfall.

Lawrence will collaborate with her co-principal investigator on the grant, Laura Peterson, assistant professor of environmental studies/chemistry at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa. Lawrence’s research focuses on long-term patterns while Peterson focuses on cyclicity, complementary skills when it comes to understanding the full climate picture. Data will be generated in both of their labs, and they will interpret the results together with their student researchers. Lawrence and Peterson plan to co-author papers from the research.

1 Comment

I am impressed that Lafayette is proceeding with science that would be useful in persuading many that while warming has happened in history, and to varying degrees of predictability, its happening now is also seriously affected by human activity and not simply geologic.

In other words, I am also impressed by Hollis Miller’s double major – and, honestly, by what seems to me a wholehearted effort to embrace the values of a liberal arts education.

More power to the Pards!

Comments are closed.