Prof. Kira Lawrence warns of the immediacy of climate change

Not everyone drilling the ocean floor is looking for fossil fuel. Some like Kira Lawrence, associate professor of geology, are looking to tell our planet’s story. And the latest story Lawrence and her Brown University counterparts have extracted from the ocean about climate change–as published in Nature Geoscience–is chilling in more ways than one.

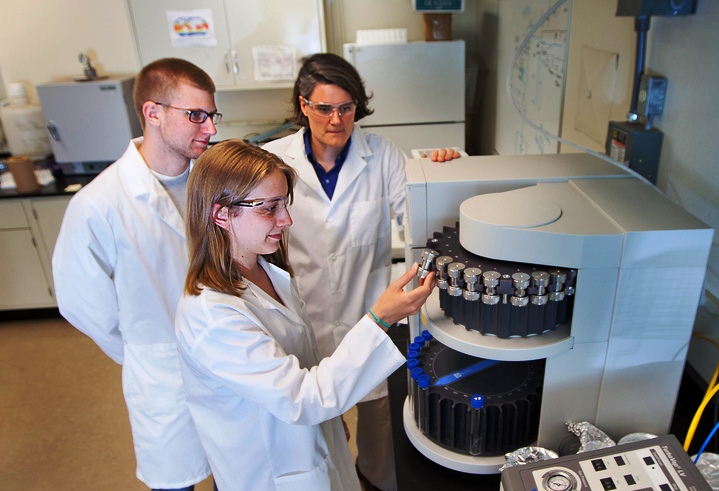

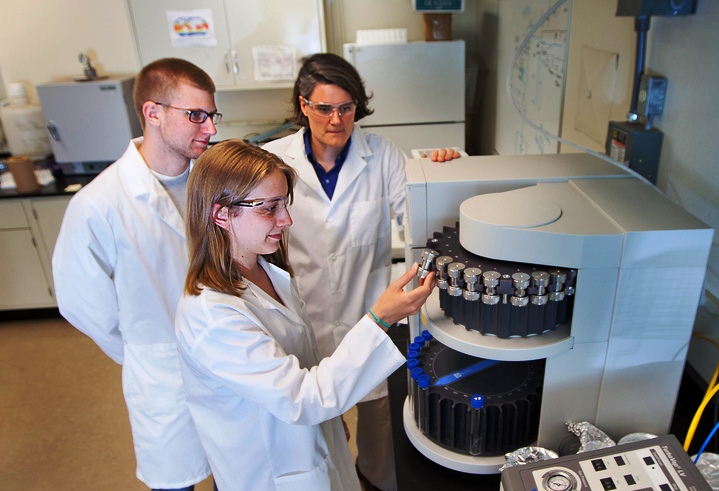

Chris Kelly ’13, Hollis Miller ’14, and Professor Kira Lawrence work in the lab.

Lawrence’s work is made possible by a global research collaborative known as the International Ocean Discovery Program. IODP vessels sail the world’s oceans punching holes in the seafloor to bring back sediment cores that scientists like Lawrence analyze to understand the earth’s processes and history.

Lawrence’s quest is to document how the earth’s climate has changed over time. As the equipment in Van Wickle Hall does not include a time travelling DeLorean, she utilizes temperature proxies. In those sediment cores are the remains of a special kind of algae, which can be extracted and translated into estimates of past surface water temperatures.

Lawrence was one of the first to use this technique (alkenone paleothermometry) to build a climate record back to the Pliocene epoch. No small feat given that was two to five million years ago. But the surprise came when Lawrence and colleagues extended that record a few million years further to the late Miocene when our modern ecosystems essentially took shape. It’s when rainforests in many parts of the Americas, Asia, and Africa became savannas and grasslands. It’s also when the first bipedal apes of the eventual human lineage appear.

Most thought these ecosystem changes were driven by regional tectonic shifts—the plates of the earth’s crust moving about—and were unrelated to global climatic changes. But thanks to the collaborative efforts of two universities and three generations of geology researchers, including Lawrence, her former Ph.D. adviser, Brown University’s Professor Timothy Herbert, and her former Lafayette senior thesis advisee, Christopher Kelly ’13, that belief is changing.

Until now, what we knew about Miocene climate was derived from a different proxy (oxygen isotopes) that reflects deep ocean temperature and ice sheet volume. It’s a great technique for picking up massive system changes like the emergence and ending of the earth’s most recent ice ages. But to detect subtler climatic shifts, a different lens offered by this surface temperature driven proxy was needed.

But it wasn’t just that Lawrence and Herbert discovered global cooling where we thought it didn’t exist. Thanks to IODP drilling and the joint efforts at several institutions including Lafayette, we have climate data from more than 17 locations spanning both hemispheres. This data paints a pattern of moderate cooling in the tropics and more intensive cooling in higher latitudes. Which has all the fingerprints of being driven by changes in carbon dioxide (CO2).

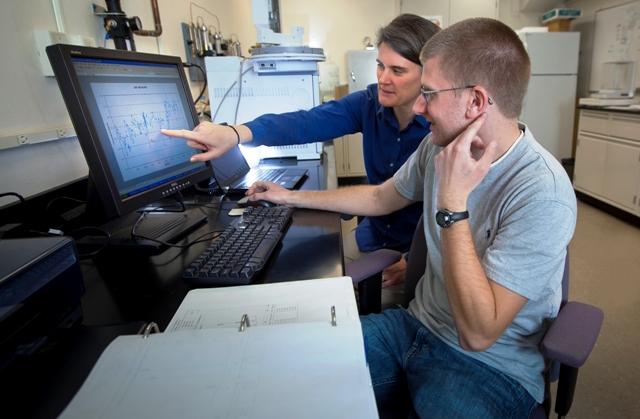

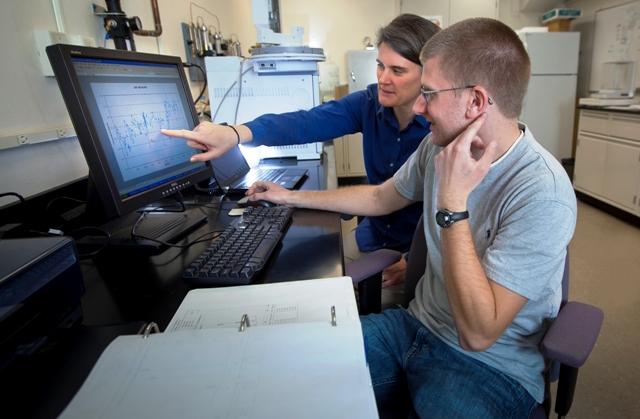

Chris Kelly ’13 goes over research results with Professor Kira Lawrence in Van Wickle Hall.

Work is still to be done, but if the earth’s cooling is linked to a CO2 reduction in this critical epoch of human development, it will draw more attention to our present day scenario where just the opposite is happening. If global cooling helped create our current ecosystems, it’s not alarmist to suggest global warming may fundamentally disrupt them.

“Climate exerts a strong control on ecosystems”, says Lawrence.

As a result of her IODP powered work Lawrence is a key player in the study of past warm climates. She knows what the planet looked like the last time it was as warm as where we are trending, which has Lawrence pretty concerned. Thankfully, it also has her fired up.

“I’m pretty passionate about this because this is undeniably a really important moment in time for this issue and for society’s ability to grapple with it. The people who actually look at how much we have to do to avoid some of the worst, they’re talking about decades, not centuries to take the necessary actions, so I’m trying to share the science.”

Fortunately, Lawrence’s opportunity to share that science has swelled with her recent selection by the U.S. arm of the IODP to participate in the 2016-17’s Ocean Discovery Lecture series. She is traveling the country to speak at numerous colleges and universities, sharing her climate change research and insights. Lafayette is by far the smallest institution represented, but Lawrence will tell you that her small liberal arts college experience is her secret weapon.

“I’m a scientist but I like to talk to other people who aren’t scientists. And if I had gone to a larger research institution, it would be all science all the time,” says Lawrence. “I would like to think that because of being in this environment where teaching is prized, the message I’m trying to share on behalf of the climate community and the ODP is one that is made with better clarity and helps people understand where we are with a greater degree of efficacy.”

The mercury is rising and the clock is ticking. Lawrence is doing her damnedest to make sure we hear it.