Play explores Muslims' often-discordant connections with Western culture

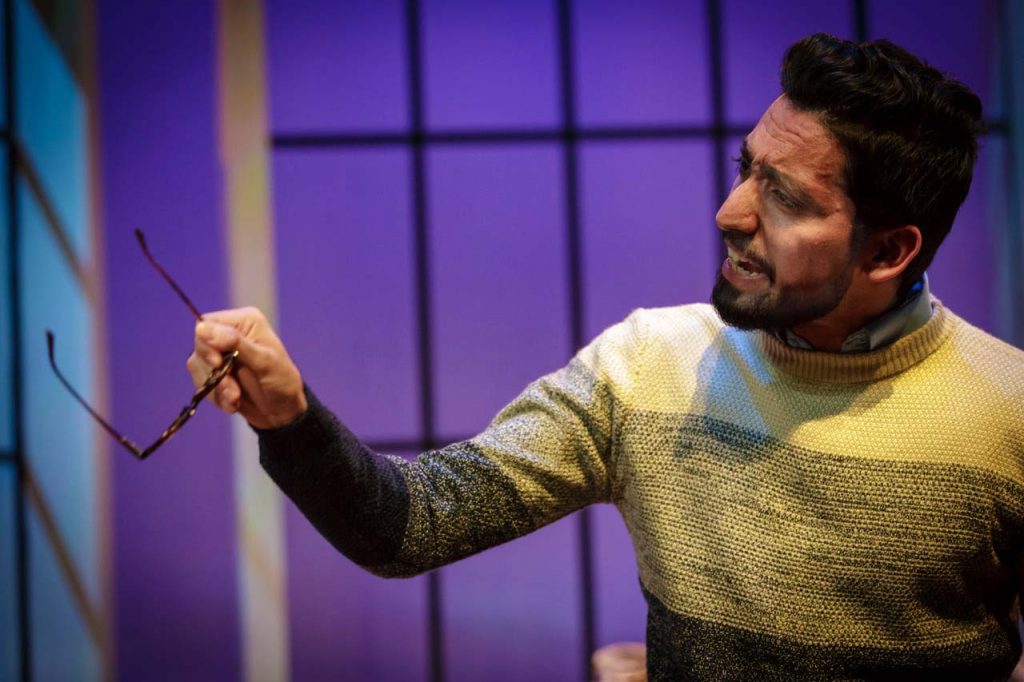

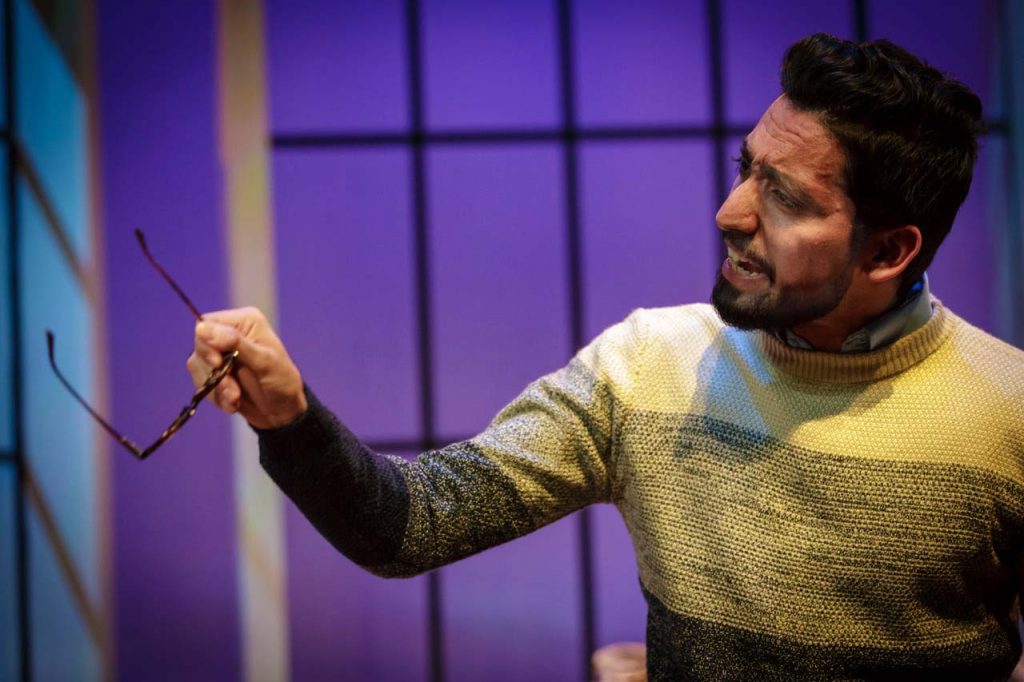

Story by Bill Landauer; photos by William Cohea

The lightning bolt struck Abdul Manan Bhat ’18 two years ago.

Youshaa Patel, assistant professor of religious studies, handed him a copy of Disgraced, the Pulitzer Prize-winning play about intersecting cultures that had been making the rounds on the New York stage. It spoke to Bhat, who hails from Kashmir, with its raw fearlessness, the way it seemed to capture the uneasiness of cultural integration. Heady stuff for College Hill, not the kind of American place where you’d expect to hear that kind of discourse—not out in the open, anyway.

Enter Suzanne Westfall, head of theater, and the Tapestries program. Westfall chose to bring the play to Lafayette after teaching it for years in a theater and diversity class. It’s a departure: Westfall usually doesn’t direct realistic plays, but she fell in love with this one.

It fits nicely into Tapestries: Voices Within Contemporary Muslim Cultures. In 2017, the College became one of an exclusive group of schools exploring Muslim arts and cultures through Tapestries, a unique blend of artistic and academic programming.

Tonight at 7:30 p.m., the Easton community will see a preview of Disgraced at Weiss Theater in Buck Hall. Tickets are available for the play’s run of Feb. 23-25 and March 1-3.

Bhat, who has never acted on stage before, will be one of two students to take on the lead role of Amir. There are two students to play each role, two sets of casts that director Westfall dubs Team New York and Team Los Angeles. Many students were interested in participating, and Westfall couldn’t turn them all away.

Bhat, who has never acted on stage before, will be one of two students to take on the lead role of Amir. There are two students to play each role, two sets of casts that director Westfall dubs Team New York and Team Los Angeles. Many students were interested in participating, and Westfall couldn’t turn them all away.

Disgraced, Bhat says, will be a “prime contribution.” Rather than a story that focuses on the beauty and understanding of another culture, Disgraced discusses Muslims’ often-discordant connections with Western culture.

Westfall and members of the cast say Disgraced has instructed them.

Watching the actors interact has been edifying, Westfall says. “The Muslims are constantly educating the non Muslims,” she says. Sometimes the lessons are small. An interpersonal quirk. For example, at one point in the play a Muslim character pleads with another not to call his mother. “All the Muslims crack up,” Westfall says. The worst thing you can do, Westfall learned, is call a Muslim guy’s mother during a fight.

Ethan Simmons ’18, who plays the role of Isaac, an art dealer, is among the more seasoned performers in the cast, having worked with Westfall in numerous other plays.

While Disgraced didn’t teach Simmons much new about the tenets of Islam, he learned something about “how beautiful and frightening faith can be.” For example, in the play Amir’s nephew Abe admires his uncle—a well-integrated apostate of the Islamic faith—because he is a successful American lawyer. However, as Abe’s beliefs become more radical, Amir is frightened. Abe eventually rejects his uncle altogether.

While Disgraced didn’t teach Simmons much new about the tenets of Islam, he learned something about “how beautiful and frightening faith can be.” For example, in the play Amir’s nephew Abe admires his uncle—a well-integrated apostate of the Islamic faith—because he is a successful American lawyer. However, as Abe’s beliefs become more radical, Amir is frightened. Abe eventually rejects his uncle altogether.

“From this exchange, I (as Isaac and Ethan) learn how [faith] can produce such emotion and ‘rage’ in people, as Abe calls it,” Simmons says. “And not just Islam, but all religions.”

Talk backs—chances to dialog after the performances—are planned with Patell; Jennifer Kelly, director of arts and associate professor of music; and the Rev. Alex Hendrickson, College chaplain and director of religious and spiritual life. It’s an explosive, often uncomfortable play that honestly faces stereotypes and profiling.

“That’s what theater does,” Westfall says. “It chronicles our times. Movies take a long time, but you can put together a play in a few weeks.”

The part of Amir takes a certain degree of courage, Westfall says. The character proclaims self-loathing and negative—often incorrect and ill-informed—ideas about his own faith.

Bhat says he’s made peace with that; he’s playing a character in the universe of the story. Amir’s experience is one that many Muslims feel at times.

The idea of Disgraced isn’t to pick on Muslims, Bhat says. Rather, the play is about people from four religious and ethnic backgrounds and how their origins and backgrounds echo through their lives regardless of their present worlds.

The idea of Disgraced isn’t to pick on Muslims, Bhat says. Rather, the play is about people from four religious and ethnic backgrounds and how their origins and backgrounds echo through their lives regardless of their present worlds.

That said, the dialog can be harrowing, Bhat says.

“There will be sentences that not have been said on the Lafayette campus in a very long time,” he says, “not even in a fictional setting.”

Tapestries: Voices Within Contemporary Muslim Cultures is made possible in part by a grant from the Association of Performing Arts Professionals, Building Bridges: Arts, Culture, and Identity, a component of the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art.

Bhat, who has never acted on stage before, will be one of two students to take on the lead role of Amir. There are two students to play each role, two sets of casts that director Westfall dubs Team New York and Team Los Angeles. Many students were interested in participating, and Westfall couldn’t turn them all away.

Bhat, who has never acted on stage before, will be one of two students to take on the lead role of Amir. There are two students to play each role, two sets of casts that director Westfall dubs Team New York and Team Los Angeles. Many students were interested in participating, and Westfall couldn’t turn them all away. While

While  The idea of

The idea of

1 Comment

Comments are closed.