Story and photos by Stephen Wilson

As a symbol of success, owning a home has always been part of the American Dream. With low interest rates and home prices rising steadily in the early 2000s, houses looked like a wise investment for borrowers and a sure thing for financial institutions. To increase profits, lenders made loans available to subprime borrowers who had shaky credit histories, unverified income, and small down payments.

If we stop right there, you already see a problem. Borrowers have been set up to fail. Ask yourself, why would they sign high-interest loans? Why would they buy homes far beyond their means? Why would a bank allow this?

These questions may seem obvious in hindsight, but at the time few were asking them. Instead, business was good until borrowers began to default. As the market slowed, the economy softened, home prices dropped, and borrowers defaulted more and more frequently. Banks foreclosed and evicted homeowners, but investors were left with heavy losses on investments they had been assured were highly reliable. As more of the subprime borrowers defaulted, long-standing financial institutions collapsed. Thus began the mortgage crisis.

It is possible that sixth-grade math classes need to share blame for this financial debacle along with bankers, brokers, and speculators?

How can rooms full of awkward preteens who are unable to work, let alone secure a mortgage, be blamed?

This is the age when many stop trying to understand math.

Fractions, decimals, percents, negative numbers, irrational numbers … the concepts feel too abstract to grasp and make understanding basic ideas more effortful. So some pupils give up.

Imagine moving through life not grasping just one of those items, like percents. How might it impact the choices you make when buying a house? Or signing up for a credit card with a low monthly payment but a high APR? Or choosing a car and its financing? Or trying to figure out which candidate supports policies that will improve your life? Or deciding between conventional and experimental treatments for your child’s medical condition?

Lacking quantitative literacy places people at risk when basic tasks demand fluency with numbers to make decisions. Making wise decisions matters the most for those with the least resources, so those who need to be the most numerate are those who often lack financial resources to devote to developing that skill.

This turns math into a social justice issue, one that Rob Root, professor of mathematics, is taking head on.

For nine of the past 11 years, Root has taught “The Mathematics of Social Justice” each fall as a First-Year Seminar offering.

“Many students see math in the title and assume there is no writing,” says Root. “But it is a writing-intensive course that uses math as a way to build community.”

The course coaches its students to reach sixth-graders who aren’t seeing rewards to studying middle school math and works to motivate middle schoolers to continue to engage with their studies.

That community starts on the Lafayette campus and multiplies out across the City of Easton.

Period 1

At 7:45 a.m., a white Lafayette van turns onto the Easton Area Middle School campus. Cars are backed up as a line of minivans and SUVs wind through the entrance loop and drop off kids. The white van slowly makes its way to a faculty lot. A handful of groggy-looking Lafayette students make their way to the front door where a large sign looms: Grade 6, 7, 8.

They stop at the security desk to sign in and grab a badge, and then head down a long hallway decorated with inspirational quotes stenciled on the walls.

Three bells sound right as the Lafayette students enter various classrooms in the sixth-grade math wing.

After the pledge and some video board announcements, homeroom blends right into Period 1. This is a math extension class for students in need of some extra help.

Creighton Hendrix ’21 and Charlotte Sullivan ’21 slide into seats alongside a couple sixth- graders. The teacher asks the students to grab an iPad and start reviewing problems on MobyMax Math, a program that finds and builds missing math skills.

The sixth-graders log into the program, which places them at their particular placement level.

The sixth-graders log into the program, which places them at their particular placement level.

They then start working on problems.

Hendrix and Sullivan offer praise as students get answers correct.

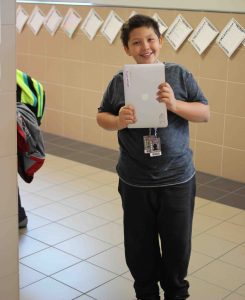

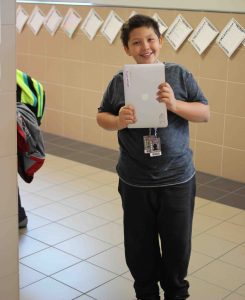

One young man exclaims, “I keep getting 100 percent!”

His enthusiasm is coupled with incentives. He earns game time on the iPad with the more math he completes.

“I’m up to 13 minutes and 3 seconds of game time,” he says. “The games are fun and strategy- based, so I still have to use my brain.”

As word problems appear on the screen, Hendrix and Sullivan use them as opportunities to talk with students about the topics. So a reference to miles becomes a conversation on triathlons and mummy tombs leads to talk about Cleopatra.

This talk might not seem like much, but it goes far.

After the bell rings and students head to second period, Hendrix says, “My student has improved a lot with simple addition. He often likes to show off in front of me.”

Sullivan adds, “We really serve as a support system to the students. My student can struggle with book work but soar with the computer. I help as needed.”

The relationship is what Root seeks.

“When you are 12 years old and an 18-year-old cares about you and finds a valuable connection with you, the students keep trying in math class,” he says. “There is a credibility and cachet that a Lafayette student has in the eyes of sixth-graders. They warm up to the college students so fast. When middle schoolers who are losing interest in math develop a relationship with a Lafayette student interested in their learning, the youngsters often re-engage.”

It seems to be working twofold: Middle schoolers whose grades had been dropping start doing well in math, and Lafayette students continue to visit the middle school after the course is over.

Math teacher Jennifer Goodyear has seen the impact over the years.

“The students in my classes who have Lafayette tutors not only have more academic success in class, but also have a person that they can talk to weekly about their lives, both in and out of school,” she says. “The tutors are also great role models for our students. They can relate to them in different ways than we can. They talk to our students about the importance of grades, good characteristics, and how to reach goals. They can reach them in places that we can’t, which creates more avenues to success.”

The Lafayette students feel that shift, and, well after this seminar class ends, they begin to commit their time at the middle school through the volunteer math program called America Counts.

Goodyear adds, “My students look forward to seeing the tutors each week and are disappointed when they are not in class. The last day is always filled with questions like ‘Why do you have to go?’ and ‘Why can’t you come back?’”

Non-randomness

On the second floor of Hugel Hall, Root greets students as they file into his class. Soon he is reviewing due dates and information learned at a recent trip to Skillman Library.

Conversation shifts to the game show Let’s Make a Deal. Its long-time host Monty Hall has just died, so talk moves to the math problem that bears his name. The Monty Hall Problem is a probability puzzle whose answer seems very counterintuitive, and Root observes that probability is a branch of mathematics that people frequently have difficulty with, despite its broad utility.

Derived from the show, the puzzle focuses on three doors. A game show contestant selects one. Monty Hall opens another and offers the contestant the opportunity to switch to the third door. Is it better to stay with the door selected or switch?

Most would say there is no difference, thinking there is a 50 percent chance of winning with one door eliminated. But the mathematician knows that you have a statistically better chance of winning if you switch.

Some students in the class are doubtful, so one student heads to the chalkboard to draw out the problem.

“No outcome is certain, so the choices feel equivalent,” says Root. “But the door Monty opened isn’t at random. This non-randomness affects the probability in this situation.”

That same morning in class, conversation shifts from Monty Hall to a larger calamity in the news from the evening before … the mass shooting in Las Vegas. After students share the details they know, including the number of dead and injured, Root asks a profound and almost rhetorical question: “Considering this is a class about numbers and social justice, how do we feel about this?”

There is not enough time left in class for students to draw on personal experience let alone stories from their textbooks, Radical Equations and How Not to Be Wrong: The Power of Mathematical Thinking.

But Root wants them to think, wants them to see how math changes their view of the world, and wants them to protect sixth-graders from becoming “early casualties in the death march to calculus.”

“Set aside national tragedies and consider the personal ones if we don’t do something to talk about math,” says Root. “Imagine planning for retirement, understanding a medical diagnosis, or completing income taxes. It’s impossible.”

He knows that college students can’t talk 401Ks with sixth-graders, but they can bring an appreciation for the math they learn, like Macquarie Simon ’21 does.

The students all call her Q, and she knows them all, floating from table to table.

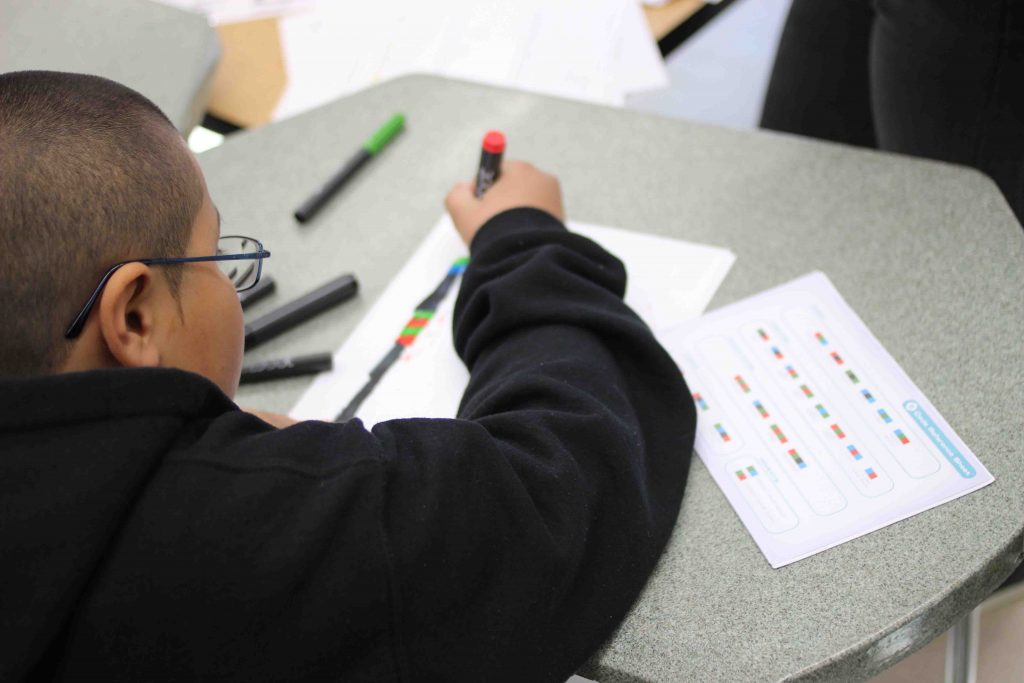

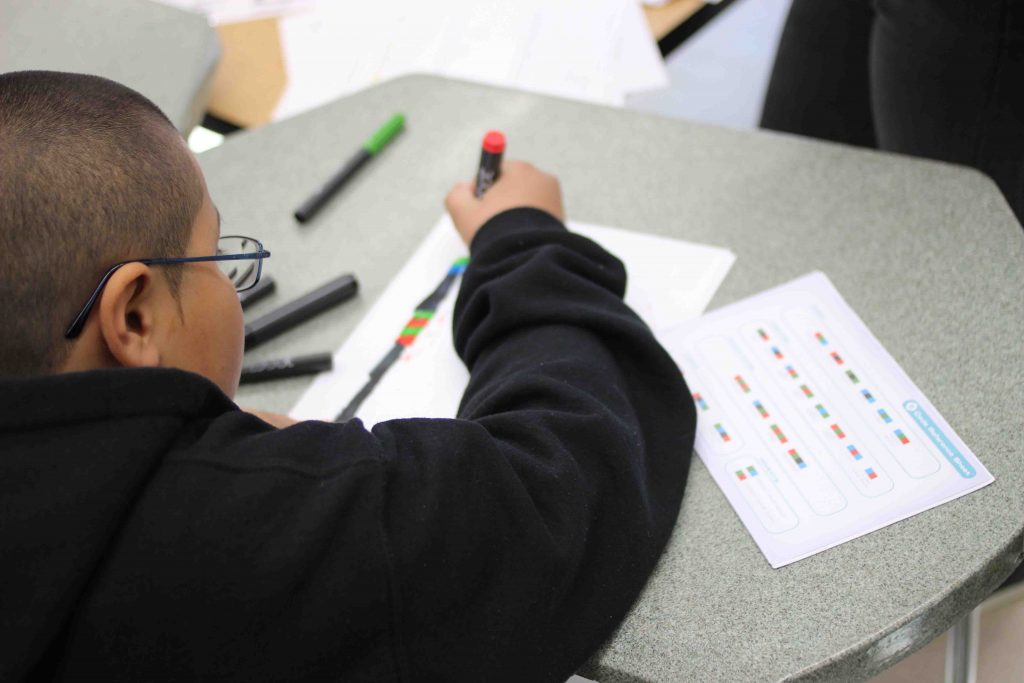

Simon checks in with a student about an out-of-class issue, and then turns to help another with that day’s assignment. Students are using markers to draw codes on white paper, and then grabbing an Ozobot that reads the code and responds.

The tiny robots are flashing, spinning, turning, speeding up, and slowing down, all based on the student’s marker map.

Simon is a natural with the students, at ease, relatable, and engaged. She talks about her background and listens to theirs. While robots follow mazes drawn on paper, the students seem less likely to get trapped in a maze that finishes in a math dead end.

At this moment there is a balanced equation thanks to Root and his students. Both the sixth- graders and the college students are finding a starting point for a new relationship with numbers.

Over the semester, the Lafayette students come to a deeper appreciation for the value of lower mathematics not only as a stepping stone to the quantitatively sophisticated careers to which many of them aspire but also as a means to understand the world, make life decisions, and communicate. They bring that appreciation to the middle schoolers at a moment when they need it, when peer pressure and wider culture conspire to undermine their commitment to their own education in a discipline that is more important than our society often acknowledges.