Through columns, arches, and siege towers, new classics course delves into Roman technology and engineering

Story by Bryan Hay, photos by Clay Wegrzynowicz

In one of the classic scenes from Monty Python’s Life of Brian, opponents of the Roman occupation of Judea complain of generation upon generation of persecution without the Romans giving them anything in return.

One by one they start to sheepishly speak up: nothing from Rome, that is, except for the aqueduct, sanitation, roads, irrigation, public baths, education.

Rome wasn’t built in a day, but a new 300-level course in the classics catalog, Roman Technology and Engineering, is unearthing the political, social, and environmental conditions that inspired the ingenuity and know-how that sustained one of the greatest civilizations in history.

“I’ve been interested in the Roman world ever since I took my first Latin course in high school,” says course instructor Jason Simms, an instructional technologist and one of several members of Information Technology Services who enters Lafayette’s classrooms to not only teach but also gather insights about how technology can improve learning.

“I ultimately ended up pursuing a major in that for my undergraduate degree, and at the same time I’ve spent my entire working career in technology in one form or another,” he says.

“I took a course much like this as part of my undergraduate career, and it really stuck with me,” Simms adds. “Even though I’ve taught at several institutions, I’ve never had the opportunity to do something like this.”

So when Simms started talking with Markus Dubischar, who heads the classical civilization program, about a potential new course, one about Roman technology and engineering was at the top of Simms’ list.

And it ended up being a natural interdisciplinary fit because of Lafayette’s STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) focus.

“One of the things that I try to teach my students is that I don’t view technology as a thing,” Simms says. “It’s not something that’s made and used. To me, technology is the application of knowledge to a practical problem. In that sense technology is a verb.”

That process, he explains, is wrapped up very tightly with the social, political, environmental, or economic context of whatever society is being examined.

“In this case, it’s Rome,” he says. “Just like any other group of people, they had problems to solve. The means by which they solved those problems often expresses itself in the technologies that we see.

“It’s interesting to not just look at the technologies, but to say what were they trying to solve, why were they trying to solve it, and what facets of society did these things intersect through,” Simms adds. “That’s why I think it’s a nice interdisciplinary fit at Lafayette.”

The new course very explicitly talks about the contemporary relevance of ancient Rome, and Simms regularly asks his students to come up with examples of how Roman technology still influences the modern world, including architectural features on campus.

“We even talked about the knock-off counterfeit marble trade that was becoming fashionable in the early Roman Empire,” Simms says. “The best marble was only accessible to those of the imperial court, those who had favor or wealthy senators.”

Marble, hard to mine and ship from long distances, was expensive and in demand. “A whole secondary market opened up for private buyers who wanted to have what the Caesars had, essentially,” he says. “They got stones that were close. We see this today. Everybody wants marble countertops, but maybe that’s out of their financial reach. But quartz is close and just as durable and a lot cheaper. And we got into a discussion on how we see that same thing with high-fashion luxury goods today.”

Not necessarily temporally organized, the class runs the gamut of Roman technologies and innovation. For example, Simms is exploring broader topics such as how the Romans measured time and worked stone to how they planned and engineered cities, moved water in vast, often harsh environments, and used technologies in producing ceramics, glass, and decorative arts.

“What were some of the seminal inventions? Interestingly, the most important invention was the water wheel,” Simms says. “We spend time looking at why that arose when it did, what problems it solved, and how that one invention literally changed the whole trajectory of western civilization.”

During a recent class, Simms and his students discussed Roman arches, concrete, and construction. Arches, while a ubiquitous feature of the Roman landscape, were not a Roman invention but a borrowed element from earlier civilizations in the Middle East. But the Romans found ways to build them faster, more efficiently, and stronger using a concrete made with volcanic ash.

Later in the semester, the class will turn its attention to broader economies like agriculture and food production, and conclude with conflict and war, including a look at Roman swords, siege towers, and the trireme, the swift, ramming battleship famously featured in Ben Hur.

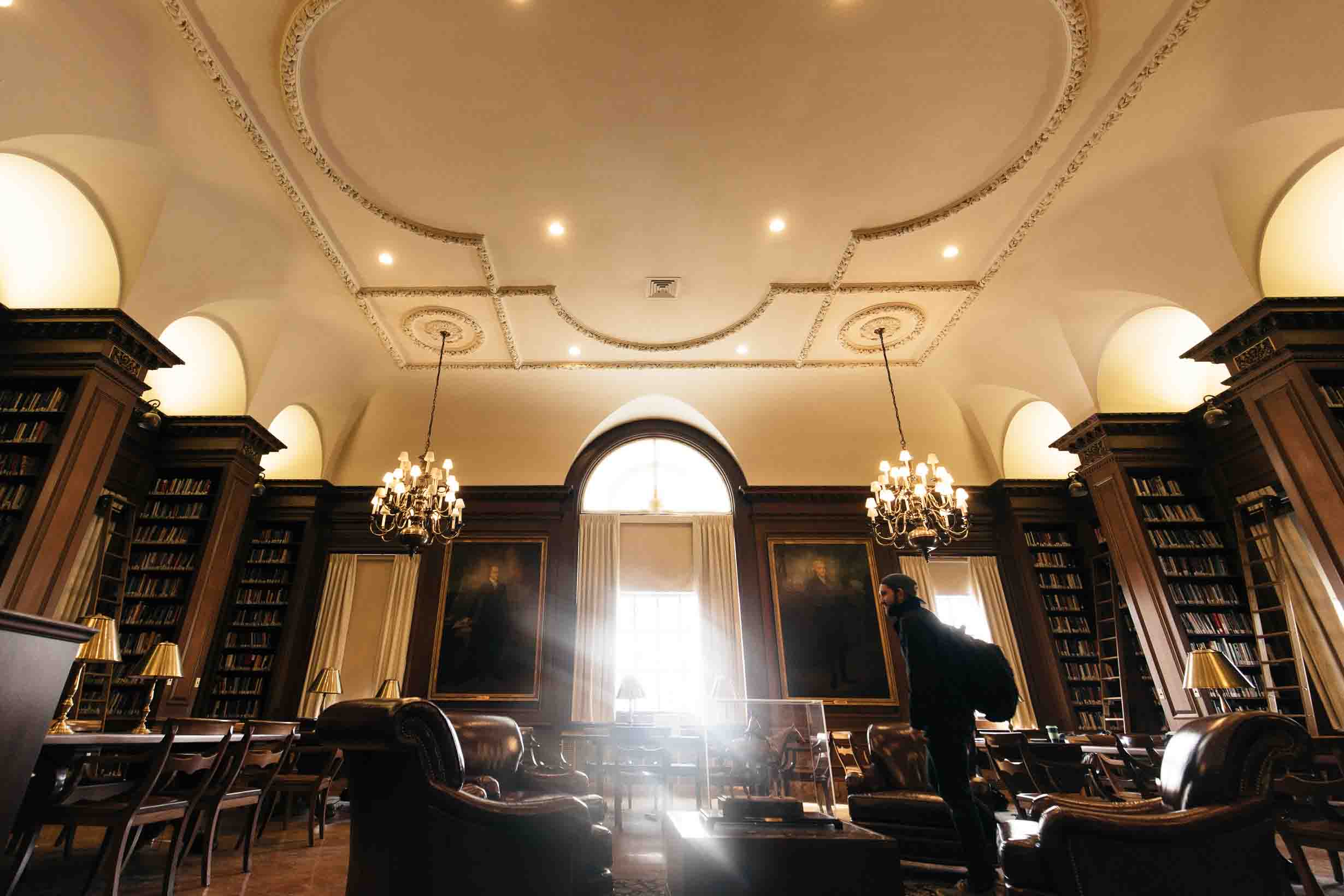

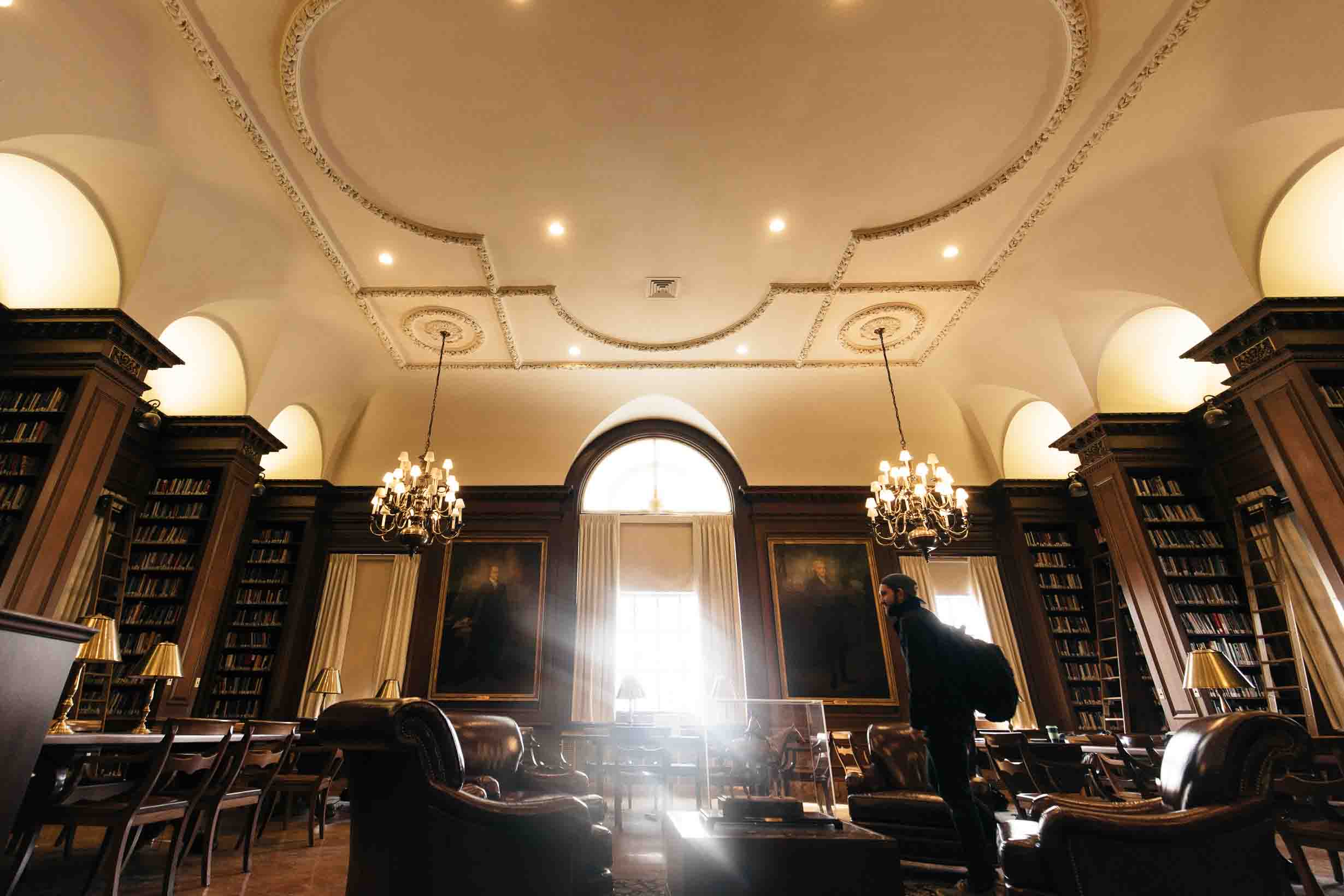

Simms has 11 students, two-thirds of them engineering majors, in the class, which meets Tuesday and Thursday mornings in Ramer History House. It’s a mix of six seniors, three juniors, one sophomore, and one first-year student.

“I’m very pleased with the reaction so far,” Simms says. “I’m sensitive to what students think and pinging them for feedback. The only way to improve is through feedback.”

Jenna Didio ’18 took the course on the recommendation of Dubischar and was immediately drawn into its title.

“I became more interested when the description included roads, aqueducts, and other aspects of civil engineering,’ says Didio, a civil engineering major. “The first day of class, Professor Simms described how we would look at not only Roman technology, but the effects it had and still has on society and the engineering process. In the engineering field, it’s important to know the cultural consequences that come with innovations and discoveries, and this class is really helping me look at that.”

She says she’s enjoying the assigned readings, one of which is a source book that has primary technical and nontechnical sources from Roman writers and philosophers.

“Again, the combination of these nontechnical philosophers viewing Roman innovation from the outside gives me a new perspective on how people outside my field might view modern engineering,” Didio says. “Overall an interesting class, and the work assigned is sort of ‘free-form’ in the sense that Professor Simms wants us to interpret the topics in our own way.”

“As an engineer, the course has been rather humbling in seeing what people two millennia ago could accomplish,” says Ian Miller ’18, who’s majoring in electrical and computer engineering and physics. “As a physicist, it has been interesting to read Roman explanations of physical phenomena.”

The Romans were very practical and empirical about their research, he adds, noting that the goal of modern physics is, by and large, to develop elegant mathematical theories that explain physical phenomena.

“For instance, the Romans did not have a unified concept of an hour; it varied in length depending on the day,” Miller says. “Now we come up with complex standards for time to define a second extremely precisely. It is challenging and eye-opening to get a glimpse of the drastically different way that the Romans saw the world: one that was concerned with understanding what worked, but less how.”

Annika Asplund ’19, a civil engineering major with a minor in geology, finds the reading materials, from classical authors to modern technological journals, very useful.

“The guided class discussions are also great because we focus on the most important parts of the readings and dive further into their meanings with regard to Roman society and today’s world,” she says. “This course is very interesting because I get to relate what I am learning in my other areas of study to the ancient world. Just the other day I was able to use my geology knowledge to further my understanding about Roman quarrying and stonework. This class is the embodiment of what I think of as Lafayette College’s interdisciplinary studies.”

For Rosario Rivera ’20, who’s intending to major in classics and government & law and Spanish, the class seemed like an interesting, complementary new take on her previous course work in classics.

“Professor Simms makes class very fun, and it is obvious that he not only knows a lot about what we are studying but also that he genuinely cares about the field and his students,” she says. “He has designed the class so that it is interactive, informative, and challenging but not too stressful.”

For Simms, the course has been revelatory, a sweeping view from the Appian Way.

“It has opened me up to new and exciting scholarship and laid bare the question of the centuries, ‘Why did Rome fall?’ ” he says. “Technology can have intentional and unintentional negative consequences. That’s been a revelation to me.”