By Stephen Wilson

A student draped in a flowing white smock steps out of Farinon swaddling a raw, bloody roast. Around her neck hangs a chain of hot dogs. Soon she is sitting in a snowbank building a hot dog fence to protect her as she rocks her roast like a baby.

Other students watching the spectacle record it on their phones and post it to social media. Soon the performance is the trending topic on Reddit and Tosh.0. It even lands in the student’s hometown paper.

On the surface this art performance and the coverage it garnered perpetuates a perception that Nestor Gil, assistant professor of art, is working to change.

“There is a myth of the artist as a misunderstood genius divinely inspired while working alone in a solitary tower,” says Gil. “People who believe this myth see an artist as something apart from ‘everyday’ people—the solitary genius is an idea in which the art market has found profit for a long time. But art is not solitary; it is social. Art’s not isolated; it’s connective.”

Gil and Lijuan Xu, associate director of research and instructional services at Skillman Library, have collaborated to help studio art students expand their sense of time and space and view art more horizontally, connecting artists and artwork across history, people, heritage, disciplines, place, and more.

Information literacy refers to a set of skills that includes identifying what information is needed, accessing information effectively and efficiently, evaluating information and its sources critically, and using information effectively.

Information literacy strategies are not commonly taught in studio art classes.

The article they co-authored, “Librarians as Co-Teachers and Curators: Integrating Information Literacy in a Studio Art Course at a Liberal Arts College,” was selected by the Library Instruction Round Table as one of the top 20 library instruction articles for 2017.

To them the hot dog and roast performance piece was not only deeply personal but also linked to what other artists have done.

“The student’s family owned a butcher shop,” Gil says. “And she wanted to make a performance that paid tribute to her family and its history.”

It was also inspired by Marina Abramovic’s work. You may remember her as the artist who sat in a chair at the Museum of Modern Art for seven hours a day, six days a week and stared for a minute or two at museum visitors who sat across from her, some 1,400 in total. Abramovic is responsible for decades’ worth of work at the edges of art and performance.

Before creating their own artwork, students conducted research to find out what other artists have worked on and why. They valued that experience. As one student wrote, “[The research] has definitely brought me freedom to work knowing that other people are asking questions and creating work on such a diverse level. The research … freed me.”

Working on the article helped Gil and Xu as well by extending their continuous collaboration.

“The provost’s office and the library have been offering information literacy grants since 2002,” says Xu. “In 2014 when Nestor was awarded a grant, he and I had many conversations about what he wanted to accomplish in ART 206 Materials and Methods. Over the course of three years, we designed projects, executed them, and refined them. While the grant ended, our partnership continues… which is the goal of the grant.”

“Art is not something pretty that is made in a vacuum,” says Gil. “Imagine an artist today painting like the Impressionists and thinking it was a new approach, or a doctor treating leg injuries like they did during the Civil War. Students benefit when they engage in conversations in art that look at histories and provide context for how and why artists create their work and the political and social realities that influence that work.”

Gil adds, “While lectures on specific art and artists are common and invaluable in studio art classes, it is even more helpful for students to see how artists’ work reflects the world and that art is connective, predictive, and responsive. This perspective helps student art become more powerful.”

Xu saw the need to share all that they were doing and learning.

“After three semesters of working together, I thought we should write about our collaboration—that what we were doing could be helpful to others,” she says.

Xu only found one article on the subject, which further convinced her that the gap in scholarship needed more attention.

“Lijuan is the farmer in the writing relationship and I am just the cow,” Gil says. “She is doing all the planning and work.”

Using a research leave in the summer of 2016, Xu worked on the article, describing the course’s structure, their planning process, information literacy assignments, studio art projects, and the course outcomes.

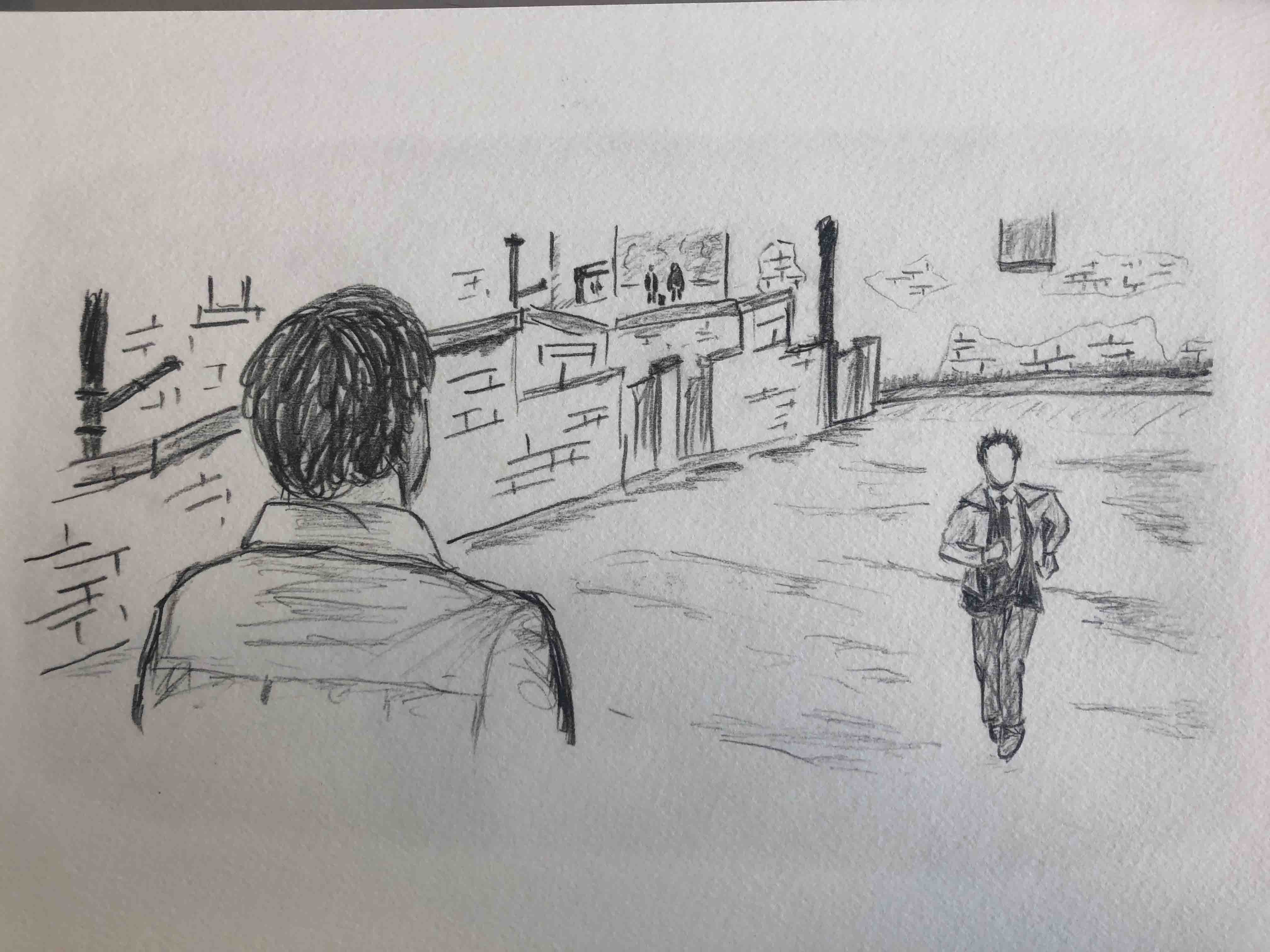

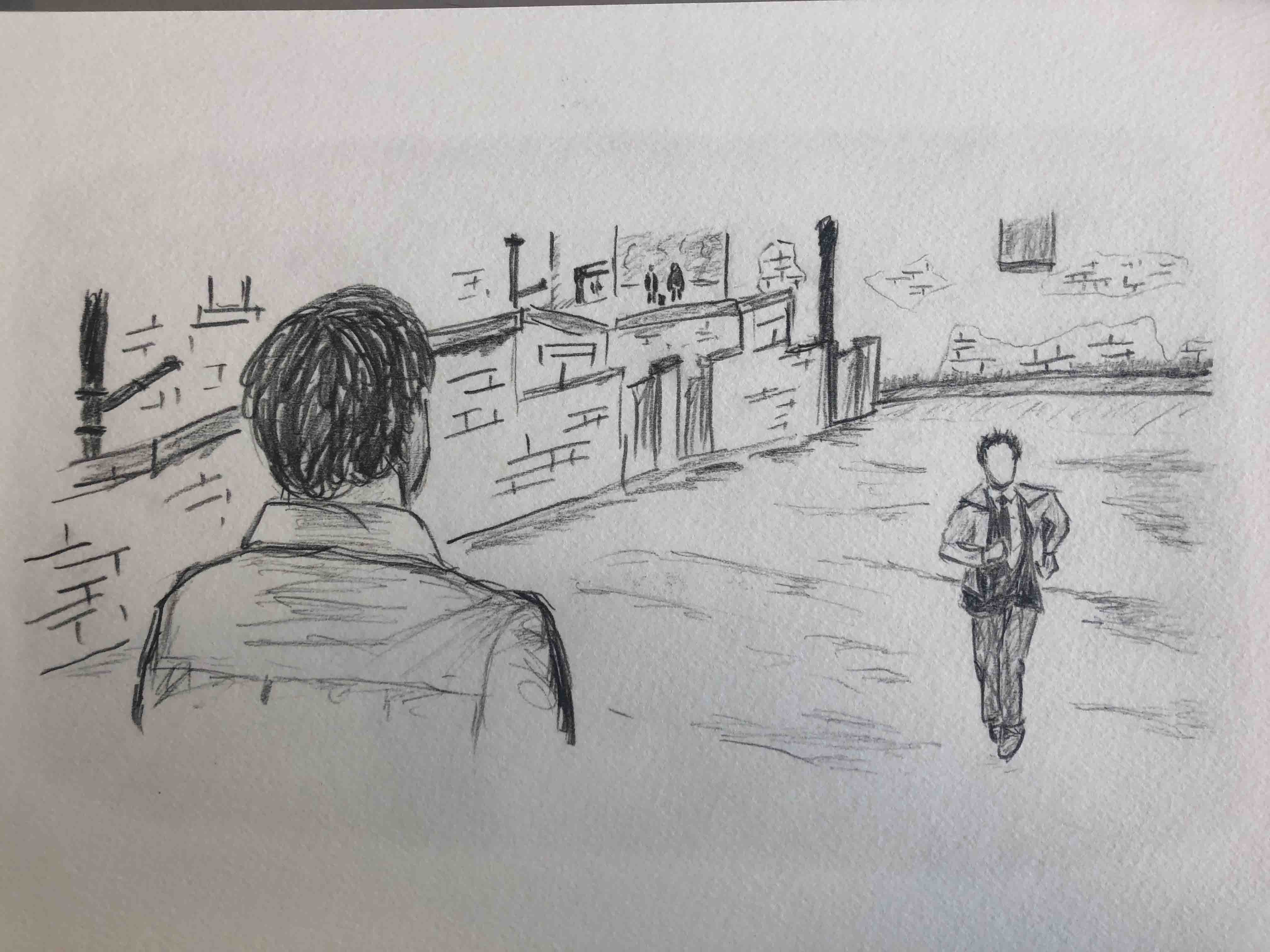

Student art was purchased by the library’s special collections department. The book, Live Oak with Moss by Mai Ao ’16, is delicately rendered—12 hand-drawn sketches based on moments in films accompanied by lines of text that appear to be decrypted messages. The piece draws from Walt Whitman’s 12-poem collection entitled Calamus that explores romantic love between men.

The drawings and text wrestle with intimacy and distance. It is a fascinating addition to the fine art collection at the College because the work is grounded in contemporary art yet unique to that student’s voice … a perfect balance of information literacy and studio art.