Terry Lutz ’62 put everything into belief that technology would enable his company to thrive

By Kevin Gray

Walter “Terry” Lutz ’62 admits he isn’t much of a gambler. But in the early 1990s, he bet the future of his company on his strong belief that the implementation of automation and high technology would allow the company to thrive. For Lutz, his confidence in his vision for growth outweighed the substantial financial investment and risk.

Lutz was owner of Signicast, a commercial manufacturer that used an investment-casting process to make products. The process involves coating a wax pattern with ceramic substance that hardens into the shape of the die. The wax then melts away when molten metal is poured into the cavity to create the product.

For example, Signicast’s largest client was Harley Davidson, for which it made parts such as head tubes, gear shifters, and footboards. However, inefficiency was a problem in the investment-casting industry.

“I saw lead times being a huge deficit to the continued growth of the industry,” recalls Lutz, a metallurgical engineering graduate. “Signicast had been growing, but I saw that we were going to hit a wall if we didn’t do something different.”

Lutz visualized the investment-casting process being like an oil refinery where materials went through pipes—or, in this case, traveled on conveyors—from one stage to the next. This vision led him to develop the concept of continuous-flow manufacturing.

“The process would be a straight line with no deviations, no going off into rework loops, and without all the other things that can slow down manufacturing,” he explains. “It would be a first-in, first-out basis. Every operation would just pick up where the last one left off with no interruptions. Nobody had to schedule anything, and nobody had to move anything. It completely revolutionized the whole industry.”

With $20 million in funding from First Wisconsin Bank—the only lender that would work with Signicast on this project—Lutz and his team built Module 1 at its Hartford, Wis., location in 1993. The entire manufacturing process was housed within one building, and it was a success.

“We went from lead times being eight to 12 weeks from a customer placing an order to receiving the product to just five days by streamlining every part of the process, even order entry,” Lutz says. “This was the biggest gamble in the world. I bet Signicast’s future that this would work. When we built the first module at Hartford, we gambled the whole company on this. We really believed our vision, and it paid off.”

Based on the transformational impact of the process, Signicast had an easier time securing funding for Module 2. As Lutz tells it, each subsequent module—and there were three more at the time—was self-funded by the company.

Module 5 was critical because, in addition to rapid lead times, it was where Signicast differentiated itself among its competitors.

“I recognized that customers wanted a finished product,” Lutz says. “They didn’t want to buy investment castings that they needed to machine or send out to a machine shop. They wanted it sent directly to their assembly plant as a finished product. That’s what Module 5 was set up to do. We actually did painting there too. That was huge because none of our competitors were giving customers products that were ready to go.”

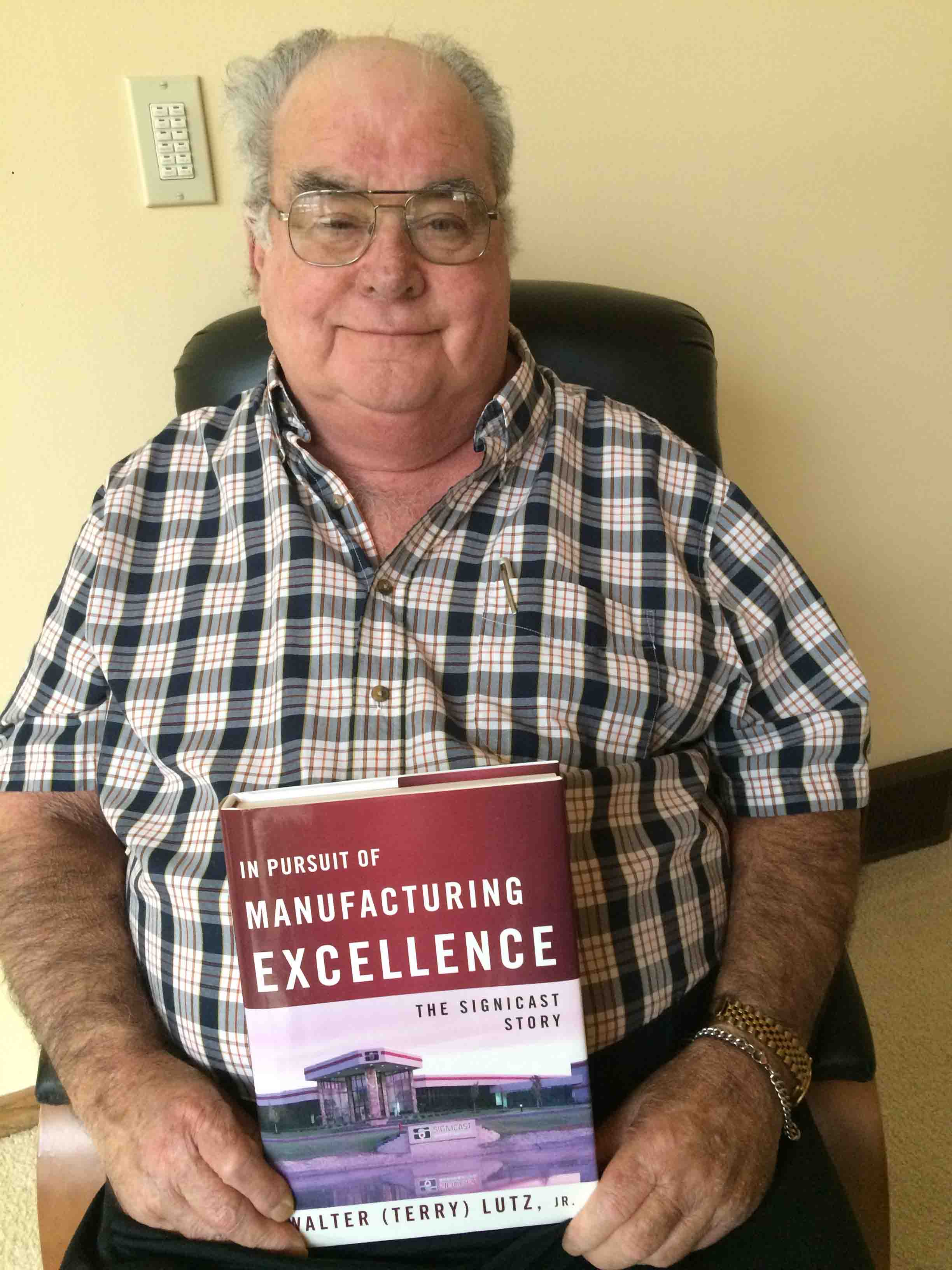

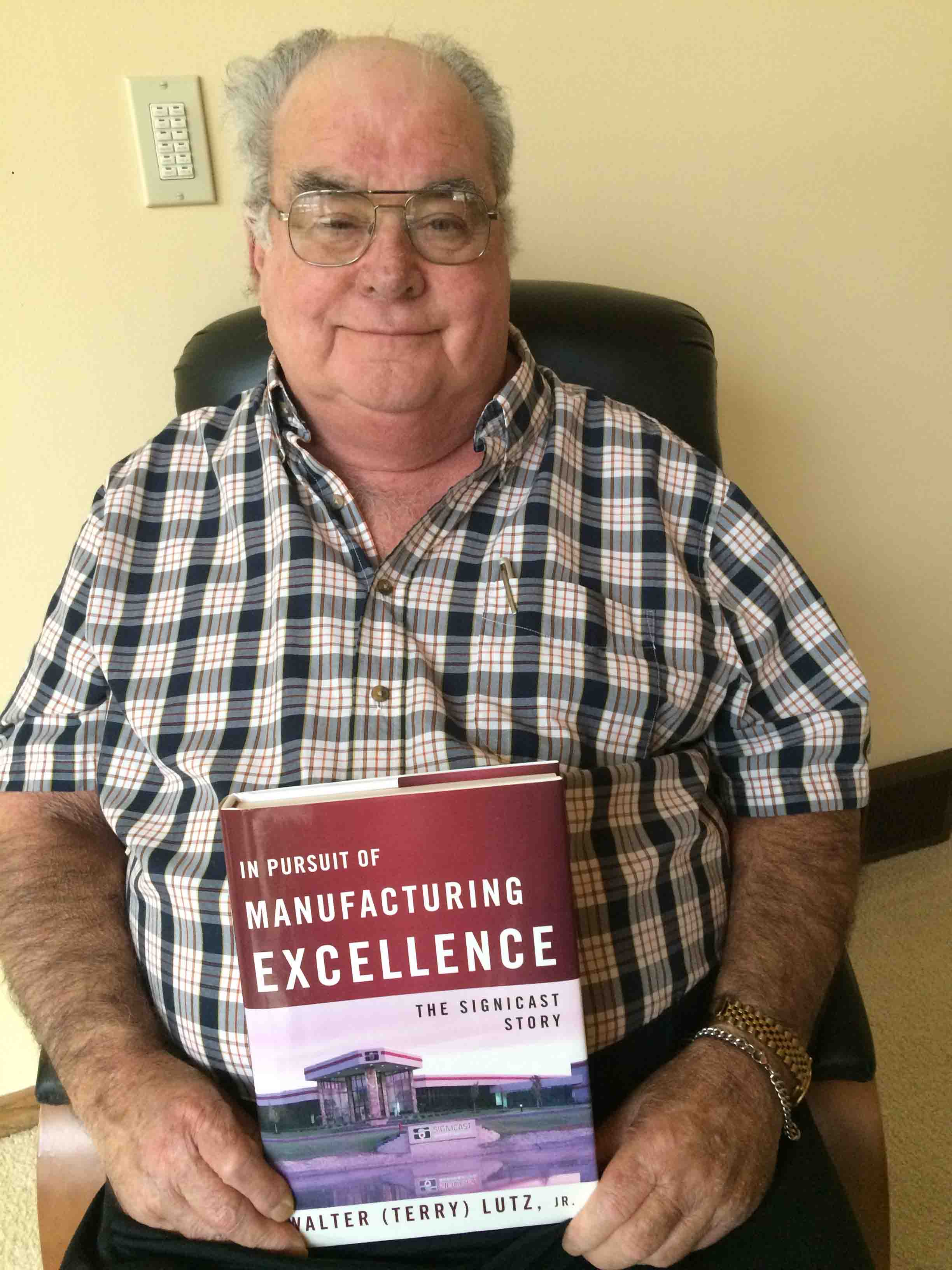

Lutz led Signicast through a period of tremendous growth—from $1 million in sales and 30 employees in 1974 to $149 million in sales and 690 employees at the time of his retirement in 2012. Lutz details his time leading the company in his book titled In Pursuit of Manufacturing Excellence – The Signicast Story.

Reluctantly in 2008, he sold Signicast to The Pritzker Group, but stayed on as president until retiring in 2012.

“I was getting old, and I didn’t want to leave the burden of having to have a fire sale at Signicast to my wife. Plus, I wanted to have the ability to choose who bought the company. So I sold and, damn it, I wound up living for all these years. If I knew that, I wouldn’t have sold it,” laughs Lutz, who now lives in Eagle River, Wis.

Still, the future of the industry and engineering discipline remain very important to him. Lutz recently donated money to Lafayette to establish the Walter “Terry” Lutz ’62 Engineering Endowment Fund. It is designated for use at the discretion of the engineering division and supports engineering equipment, facilities, student projects, and research, among other needs.

“It’s an important source of funding that will enable the engineering division and the College to continue to offer outstanding engineering programs,” says Scott Hummel, William Jeffers Director of the Engineering Division.

“I want to promote engineering because I think it is extremely important for manufacturing in the United States,” says Lutz. “For the United States to be a leader, it has to be able to manufacture, and engineering is the key component for that.”