Tapestries program funded exhibits, speakers, and productions that celebrate Muslim culture

By Heather Mayer Irvine

Lafayette College’s participation in a special grant has worked to break down Muslim stereotypes and celebrate Muslim culture through art on and around campus.

In 2017, the College was selected for Tapestries: Voices within Contemporary Muslim Cultures, a grant funded by the Association of Performing Arts Professionals, Building Bridges: Arts, Culture, and Identity, a component of the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art.

The grant is ending this semester, but not without leaving a lasting impact on the Lafayette community. (Watch a video about the grant’s impact on the campus and learn more about the programming.)

“At Lafayette College, we have a growing population of students and faculty who are more and more willing to have inclusive teaching in class,” says Ayat Husseini ’20, an international affairs and anthropology & sociology double major. “Tapestries is in concert with a lot of what we want to do at Lafayette with regard to diversity.”

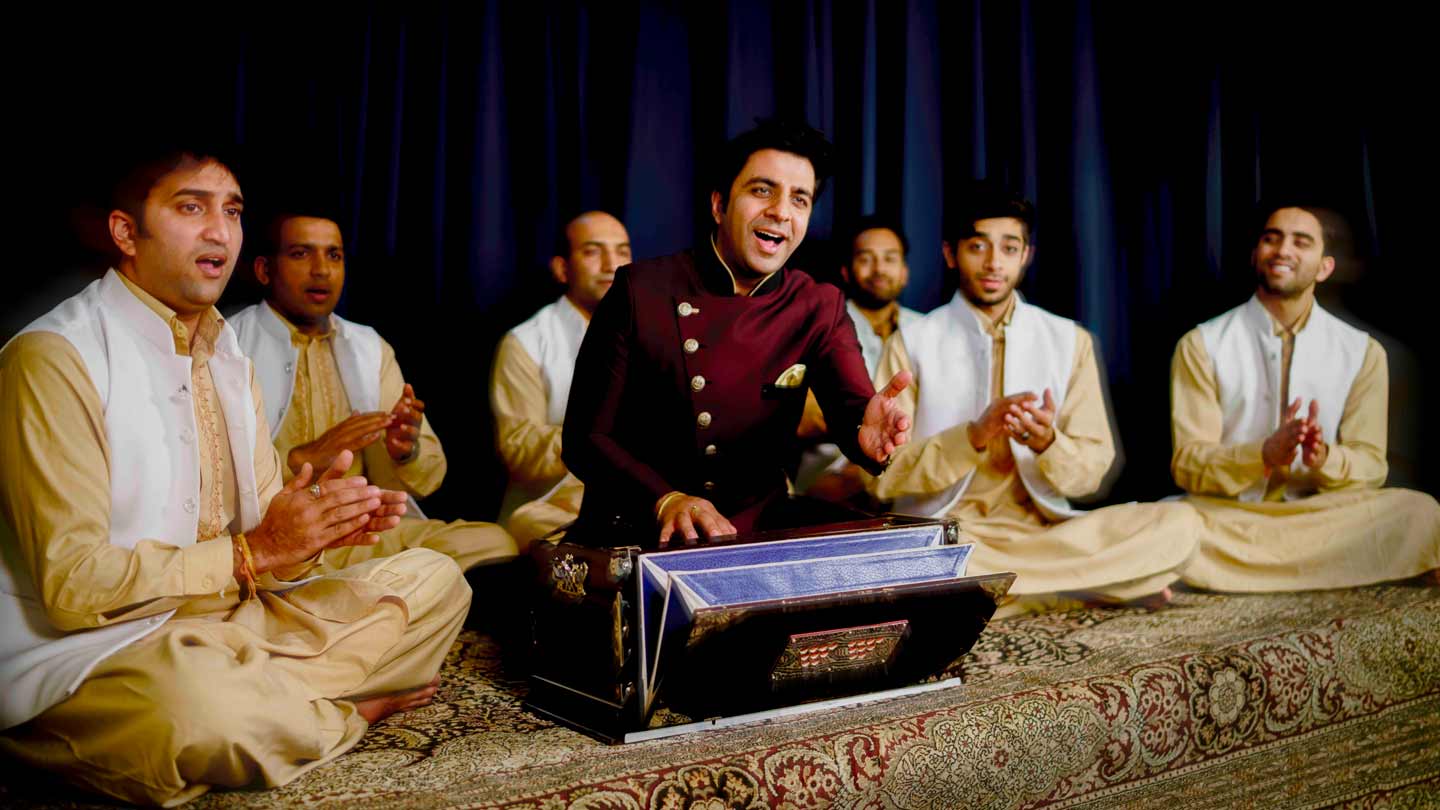

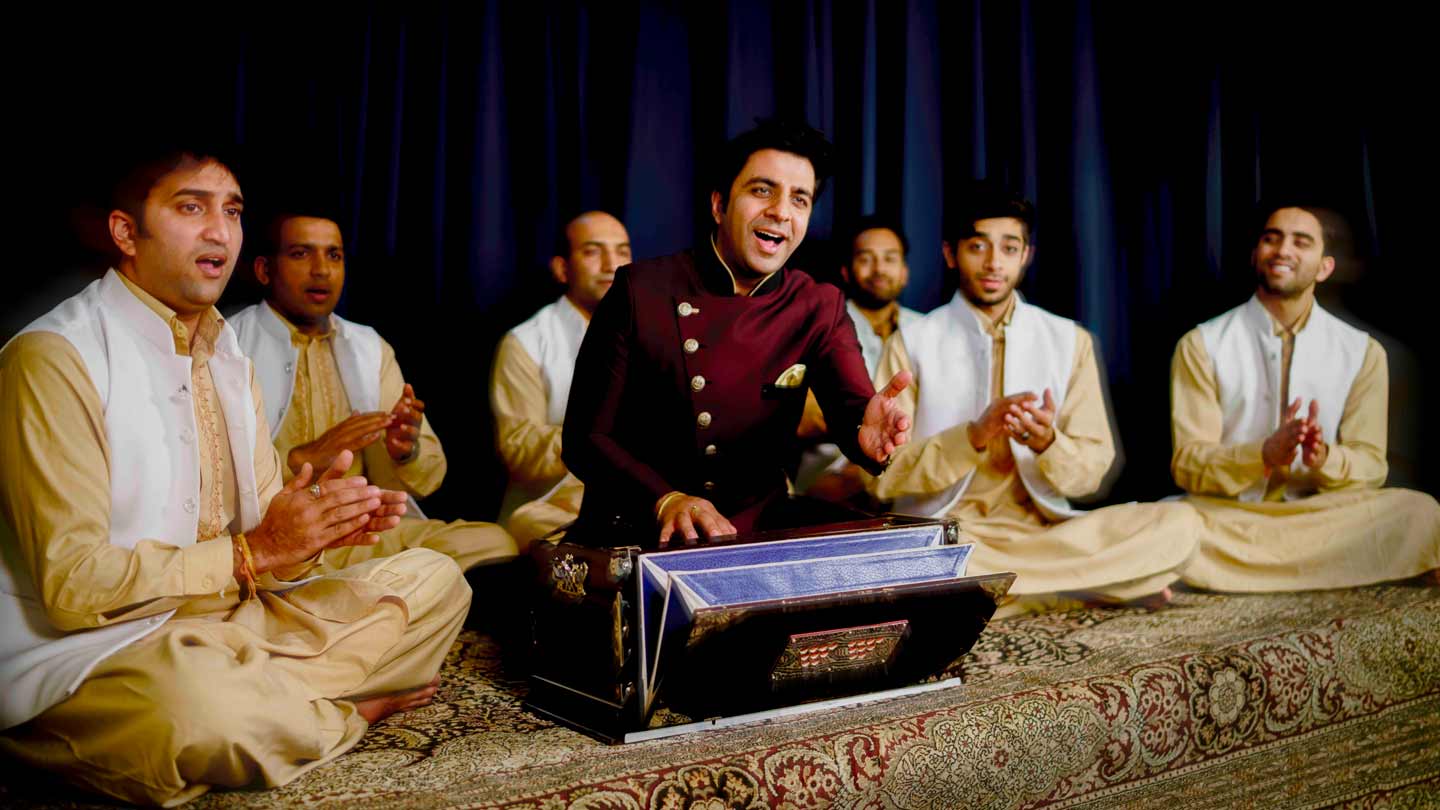

Texas band Riyaaz Qawwali visited Lafayette to perform Sufi devotional music.

Jennifer Kelly, director of arts and associate professor of music, says the objective of the College’s participation in the program is to recognize the vibrant diversity of Muslim arts, culture, and identities.

“We all deserve to live our truth—proud, open, and alive,” says Kelly who, with help from the Rev. Alex Hendrickson, College chaplain and director of religious and spiritual life, and Hollis Ashby, artistic and executive director of the Williams Center Performance Series, and with input from numerous faculty, staff, and community members, helped bring the Tapestries program to Lafayette.

“Programs such as Tapestries explore, celebrate, complicate, express, and create dialogues in a place where the free exchange of ideas should be welcome,” says Kelly.

Over the past three semesters, those involved with the Tapestries grant have brought a range of programming to campus, including jazz artist Cheikh Lô and photographer Lalla Essaydi, as well as performances and residencies in Williams Center for the Arts and a Department of Theater production in Buck Hall.

Senegalese singer Cheikh Lo performed with this band at the Williams Center and participated in prayer on the Quad.

Taha Rohan ’19, a chemical engineering major from Pakistan, studied Disgraced, a 2012 play that looked at Islamophobia, with Suzanne Westfall, professor of English and head of theater. He was so moved by the text that he worked with Tapestries to secure funding to bring the production to life on campus. Rohan also played one of the Pakistani characters.

“I always wanted to be part of a performance in college, and this was my chance,” he says. “Not everybody liked the play, but what we got was a lot of discussion, and that was the goal.”

Many of the events made possible by Tapestries evoked thoughtful conversations, says Kamini Masood ’19, a history major. And many event-goers were outside the Muslim community.

“People are willing to hear stories of Muslim culture, and they want to,” says Masood. “I didn’t expect that before working with the Tapestries program. That was heartening to see.”

A dinner scene in the play Disgraced

In November, members from participating colleges gathered in Washington, D.C., to discuss the programming they brought to campus with Tapestries support. Rohan, Masood, and Husseini—former president of Muslim Students Association and president of the campus’s Refugee Action—attended the summit and were moved by the experience.

“I loved seeing what other students did with the funding,” says Husseini. “The grant was created in a way that let the recipients do whatever they needed to educate their campuses.”

Rohan was struck by how art can be used in so many ways. He had seen this firsthand on campus when he worked with his math professor to bring Muslim education into the curriculum.

“Roman numerals were invented by Arabic people,” he says. “Algebra itself was originated by Arabians. We know what math is, but we don’t know where it came from. Those Islamic origins in math can be highlighted in the curriculum.”

At the end of the day, students, faculty, and staff involved in Tapestries want to show the community there is more to the Islam religion and Muslim culture than what the media shows, says Rohan.

Husseini, who’s pursuing a minor in religious studies, often asks herself what her Muslim heritage means in many contexts: what it means in Lebanon, what it means on campus, what it means in New York City (where she’s from).

A page from a Persian manuscript that appeared in Skillman Library as part of a calligraphy collection. Art historian David J. Roxburgh talked about the life and times of calligrapher Sultan Ali Mashhadi in Skillman Library.

Rohan and Husseini have found, through Tapestries, that art can help buck those stereotypes.

“So often there is a stereotype that people of color are consumers of art as opposed to makers of art,” says Husseini. “It’s beneficial to bring the idea to campus that we too make art that we can have a conversation about.”

But the takeaways from Tapestries go beyond educating those outside the Muslim community, says Masood.

“Tapestries has facilitated significant introspection within our own communities,” says Masood. “Yes, we can work to tackle Islamophobia, and we absolutely must, but there are also intra-community dynamics to think about. We’re having conversations now because of Tapestries, and that’s a really important part of the program.”