Composer Libby Larsen creates At the Forks for Lehigh Valley; debut set for April 7

Composer Libby Larsen

By Bill Landauer

For four days in September, members of the Easton area, Lafayette’s hometown, fielded two provocative questions from an auspicious visitor. “To whom do you pray,” asked Libby Larsen, an internationally renowned composer, as she toured sites like the Canal Museum, Sigal Museum, downtown Easton, and Lafayette’s campus. “And what’s the prayer?”

These questions are the central part of Larsen’s research into the Lehigh Valley. Larsen has been commissioned by Lafayette to compose a mixed-voice chorus and orchestra piece about the region as part of a larger celebration of the valley’s cultural heritage.

The brainchild of Larsen and Jennifer Kelly, Lafayette’s director of arts and associate professor of music, the piece, At the Forks, will debut April 7 at First Presbyterian Church of Easton. The commission was funded through a generous grant from the Hearst Foundations, and the concert in total also is funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation through Lehigh Valley Engaged Humanities Consortium, Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, and Lafayette Alumni Chorus. Performing will be 75 singers including the Lafayette College Chamber Singers and Kelly’s nonprofit community ensemble, Concord Chamber Singers of the Lehigh Valley. Additional soloists will perform, including tenor Emmett Cahill of Celtic Thunder.

Jennifer Kelly, director of arts and associate professor of music

“It’s a community event,” Kelly says. The performance will celebrate the valley’s rich history of cultural diversity, including indigenous, immigrant, and African American populations, and is written in multiple languages. Partners include Easton’s National Canal Museum and Sigal Museum, Northampton County Historical and Genealogical Society, and the Lehigh Valley Engaged Humanities Consortium.

Larsen’s tour of the Easton area was of the four-day, whirlwind variety. The Wilmington, Del., native, who today lives in Minneapolis, has had a distinguished career that spans half a century. Her compositions number in the hundreds. Her name is familiar in the Lehigh Valley. Her cantata, It Am–The Shewings of Julian of Norwich, was co-commissioned by the Bach Choir of Bethlehem and the BBC, and performed by the choir at the BBC Proms in 2003. She’s only composed seven other pieces like the work she’s composing for Concord Chamber Singers and Lafayette about the Lehigh Valley.

During her visit, Larsen answered a few questions about her research, her work, and how to find the heart of a community.

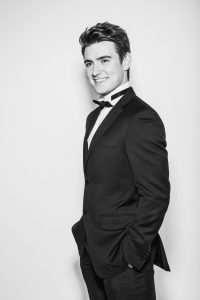

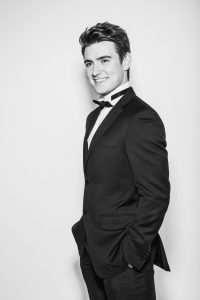

Tenor Emmett Cahill of Celtic Thunder (photo by Brendan Duffy)

How well do you know the area?

Do I know my way around, if I were given a car? No. But over the years as I’ve visited and worked in and around the Lehigh Valley, with the Bach Choir of Bethlehem and the Lehigh Valley Chamber Orchestra, I feel I’ve become familiar with the heart of the Lehigh Valley in and around Bethlehem. Now having spent concentrated time during my four-day visit in Easton last September, I hope I’ve gained a feel for and possibly an understanding of how 300-plus years’ many waves of immigration to land that retains its original, indigenous spirit, are shaping Easton’s vibrant, diverse, ongoing narrative of becoming. Coming away after listening to the performance of At the Forks I hope the audience feels the strength and beauty of diverse peoples creating one narrative made of many narratives. There’s a depth and a universality and timelessness that I am looking for. That’s what I call the heart.

There is something else that excites my creative juices about Easton and its surrounding area. I am a transportation nerd. A lifelong fascination of mine is with systems we humans devise to transport our goods, people, and ideas. I live in Minneapolis/St. Paul, situated on the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers. I was excited to see what connections might exist between Easton, situated on the confluence of the Delaware River and the Lehigh River, and where I call home. Besides both locations being natural transportation hubs and therefore hosts to human activity, I’ve come to understand that the connections are ancient, sacred, and possibly beyond our comprehension.

Lafayette Chamber Singers

Talk a little about your mechanics. How do you compose?

When I’m composing during the daytime my desk is our dining room table. It’s large, and I need the space to spread out my expansive thought in imagined time. For me, the computer screen just does not cut it—it’s too small and curtails my imagination. I alternate between my dining room table and my piano. I have to get up and walk through the front hall into the living room where the piano lives. So I work back and forth between the table and piano. I use the piano at the beginning of my process, to start to begin to get the music out of my head and as a check and balance. About a third of the way through my process, I leave the piano and spend the rest of the time at the table, writing down the music that is in my head. I write by hand. My manuscripts are all in my hand. I was trained in the graphic arts of composition [writing the music out longhand], which is beautiful and dying fast. It’s a completely different process than key clicking. I have a longstanding partner who puts it all on computer because people expect to see it on computer. Except some of the best performers are asking for handwritten now, because they can get more off the page, they say. Isn’t that interesting?

How did you get involved with this project?

Jennifer and I had been talking for a long time about whether we’d ever have an opportunity to work together. We’ve respected each other’s work for decades. So when it looked like there might be an opportunity for us to work together, it took one conversation—actually a super-brainstorming session—for us to become passionate about the piece we are creating. I really love to do projects like this. To get at the heart of a place—and express it in music. This is not pageantry, it is something else.

You’re after something deeper?

I think so because after all, we are all living together. We’re all busy making livings and working together and being productive, and that’s terribly important. It’s equally important that we work together in as peaceful, nonjudgmental, noninterfering, cooperative way as we can manage to create. [In Easton] I met with wonderful, generous people, who offered their honest perspectives. In each conversation I tried to ask two questions: When a person emigrates, to whom do they pray, and what’s the prayer? … I’ve been asking that and getting really interesting responses.

Concord Chamber Singers of the Lehigh Valley

Why ask that?

It took me a long time to figure out that these were the questions I wanted to think about for At the Forks. I am less interested in the question, “Why did you come here?” than I am in the first two questions. In the last section of At the Forks, I set the Lord’s Prayer in several languages, as a kind of meditation on the question “To whom do they pray, and what’s the prayer?” It’s lovely to hear how much the music of each language comes directly from the language itself. Aramaic, Gaelic, Hebrew, Lenape, Lakota, Welsh, German, Latin, Italian … all languages have their own distinct music. I believe that’s how music evolves—out of the language first and foremost. When I visited the Sigal Museum in September, I came away knowing that I couldn’t even begin thinking about the music for At the Forks without hearing the language of Lenape. I asked, “Does anybody speak that language? If I could just hear it …” [Members of the Lenape tribe in Easton kindly recorded several words so we could include them in the music and share them with our singers and community.]

How many people have you met with?

Twenty to 25.

That’s a lot in just a few days.

Sometimes that’s better. Just get it all at once. Get the heart. All in one place. It was baptism by fire. In 1985, I worked with VocalEssence, which is a choral organization in Minnesota. Our project was similar to this. My collaborator was Jehan Sadat, who is the widow of Anwar Sadat. So we flew to Cairo, four of us, to meet her in the palace. I was tasked with getting a sense of what we’re going to do artistically. We had one three-hour meeting with her on the first day. And at the end of that meeting—it was a lovely, quite formal, quite foreign-to-me kind of meeting—she handed me all of her speeches—they had been translated into English—and she said, “Now you read these and come back tomorrow and tell me what you’re going to do.” [laughs] My only answer could be, “Yes, I will,” and I did. I carry that experience with me into this experience. How do you listen with the heart and the brain when you have a half-hour with a person?

Capturing that is a tall order.

It is. And sometimes I think, “You are really arrogant, Larsen.” Yesterday, I stopped in my tracks and thought, “Should you really do this?” Sometimes, when I’m at the beginning of the creative process and this question fills my head, the answer is, “No, you shouldn’t.” But in this case, because of the way the piece is articulating itself through the community, the answer is “yes.” This whirlwind of meeting and absorbing, that’s one of the great things about spending a short amount of time. I have to absorb. I have to open myself up and absorb the energy of the encounters.

I imagine at some point in this piece there’s going to be a melding of all these different cultures.

Yes, there is.

What will that sound like?

Well, it’s all in my head.

So you know already?

I do. That’s been a blessing and a curse my entire life. I’ve always heard in full orchestral sound and full architecture. When I know what a piece is, it’s there in my head, somewhere back here in the cerebellum. After that, my process is just bringing the piece forward and out. There’s a moment in this piece everything comes together. All the perspectives and all the prayers will come together as one—music and word, but the moment is neither. You know Beethoven’s Ode to Joy? The words and the music are there, but it’s the moment that is transcendent. That’s why I’ve composed all my life—to get this moment in every piece I compose. I just want to get this elusive, brilliant moment.