Former civil engineer and entrepreneur Howard Schoor '61 is now "working on becoming a starving artist"

By Bryan Hay

A classically trained professional civil engineer, Howard Schoor ’61 helped design and build the approach roads to the Verrazano Bridge and achieved success leading one of the largest engineering firms on the East Coast from 1967 to 1992.

Now, at the spry age of 80, he says, “I’m working on becoming a starving artist.”

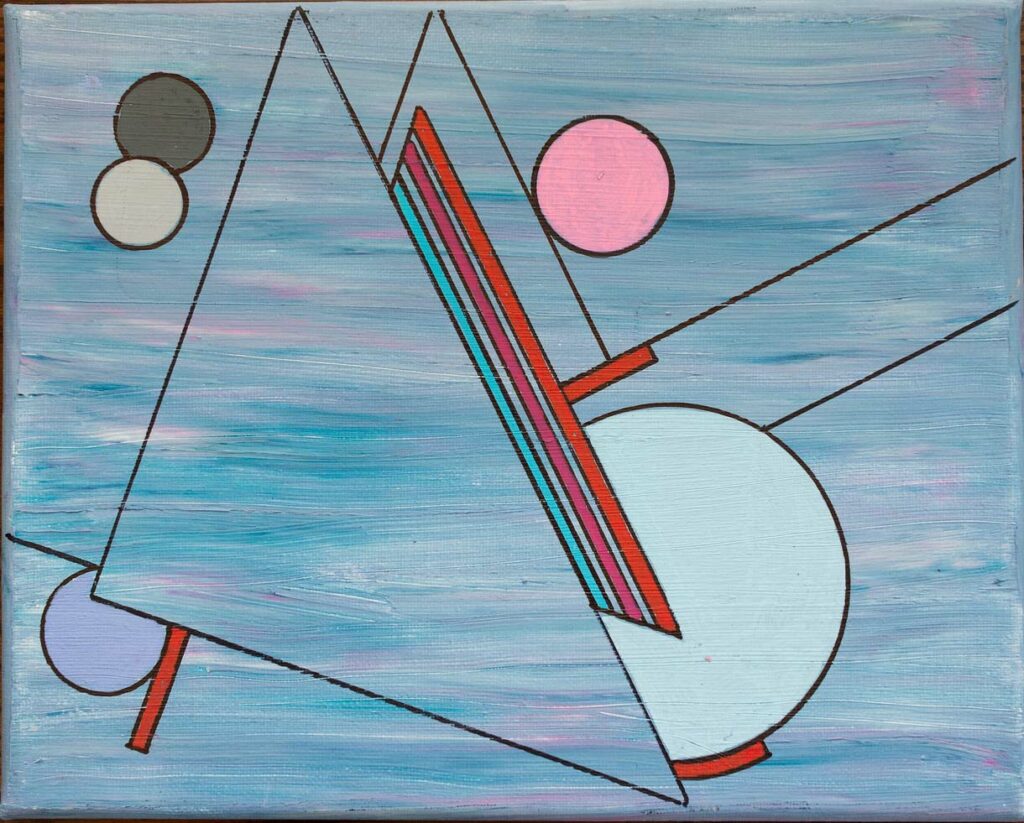

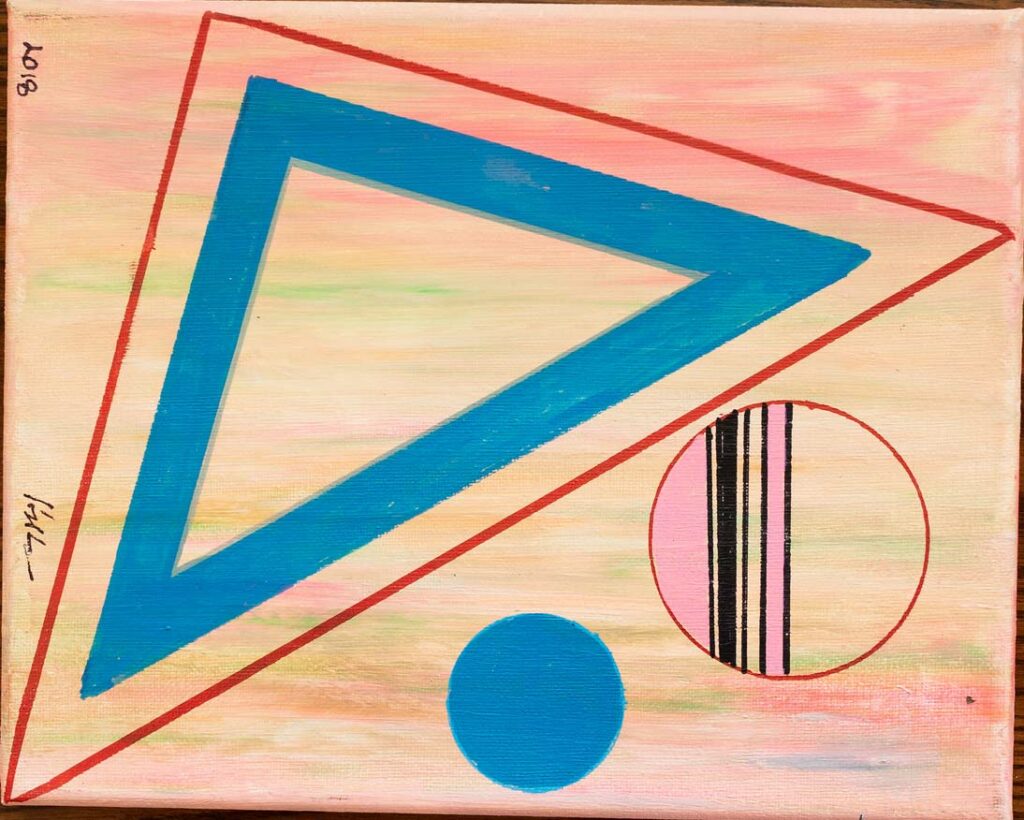

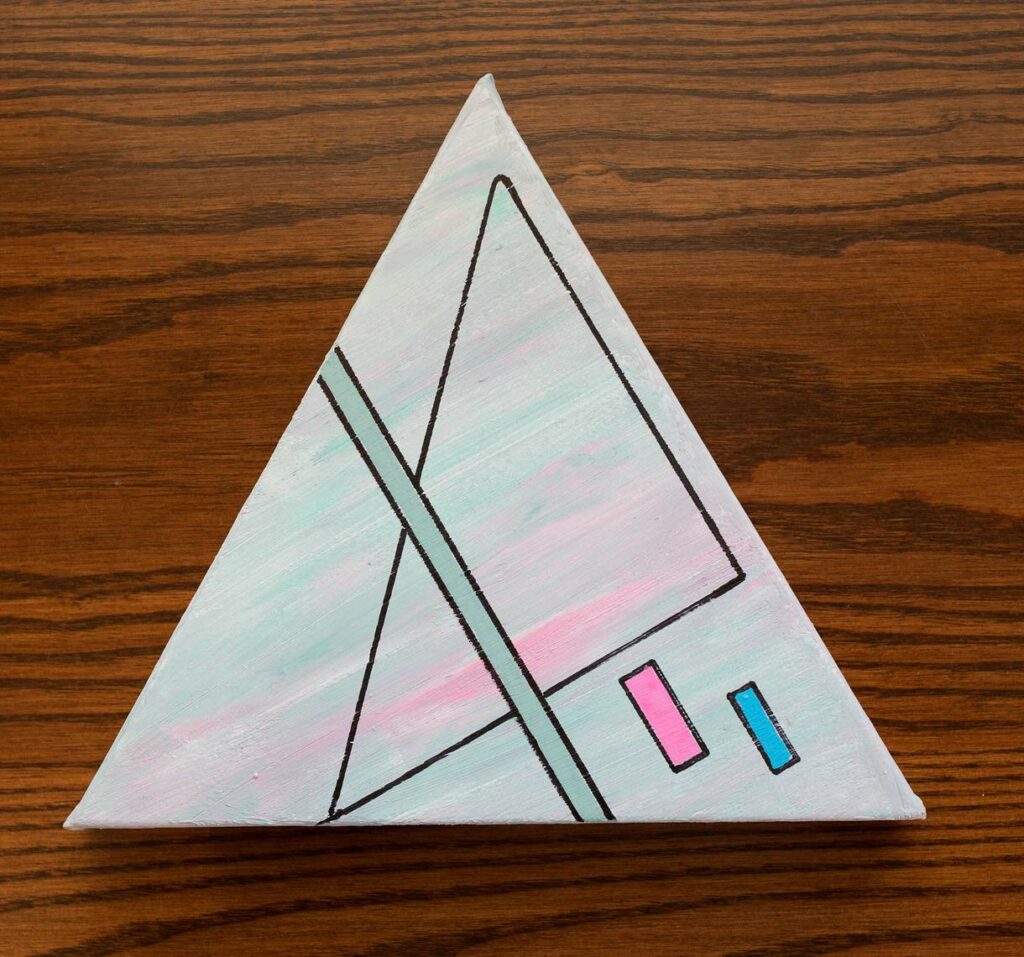

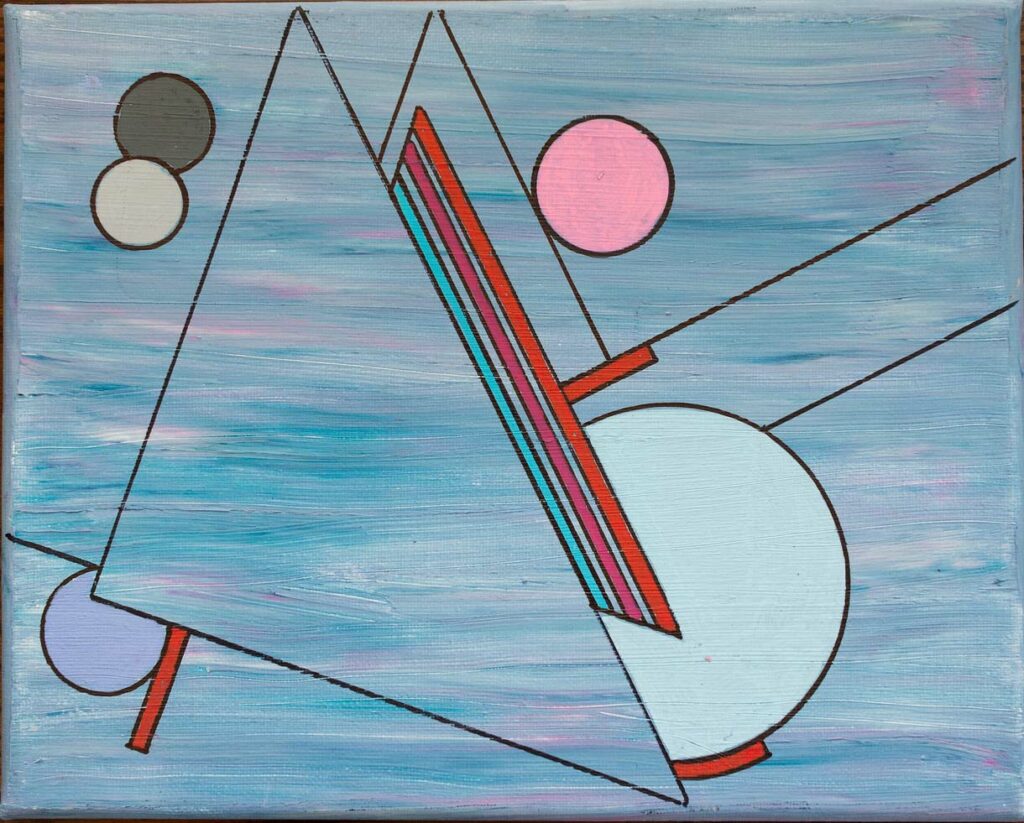

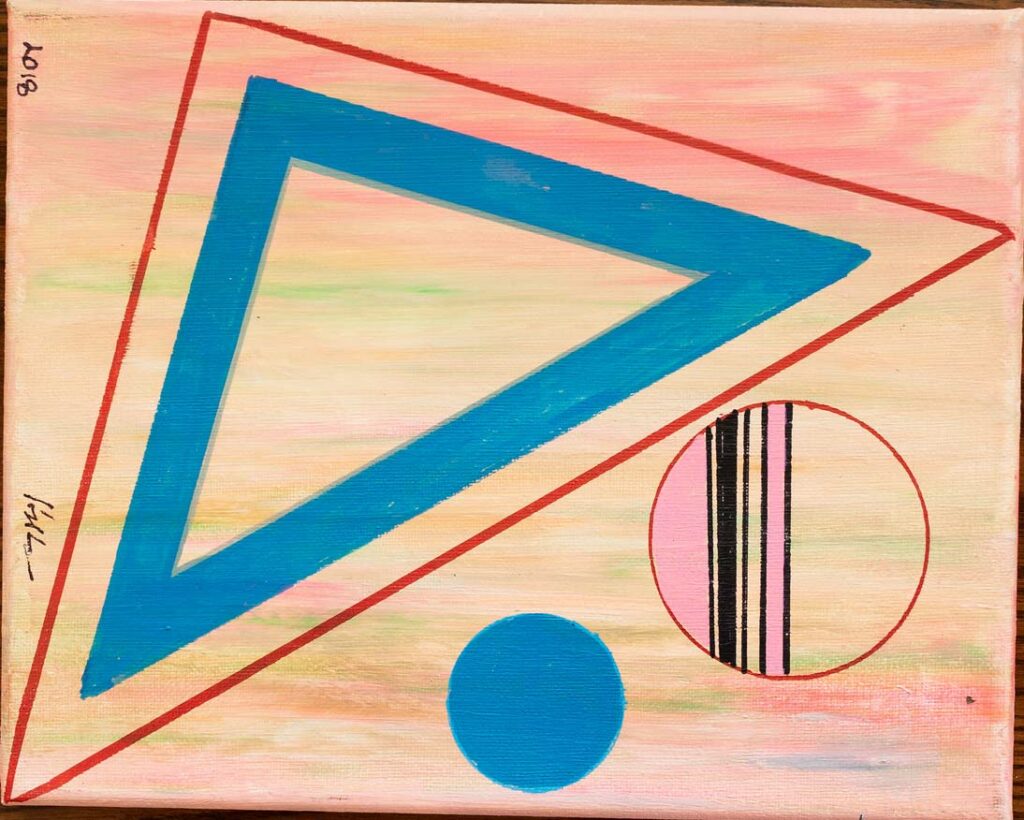

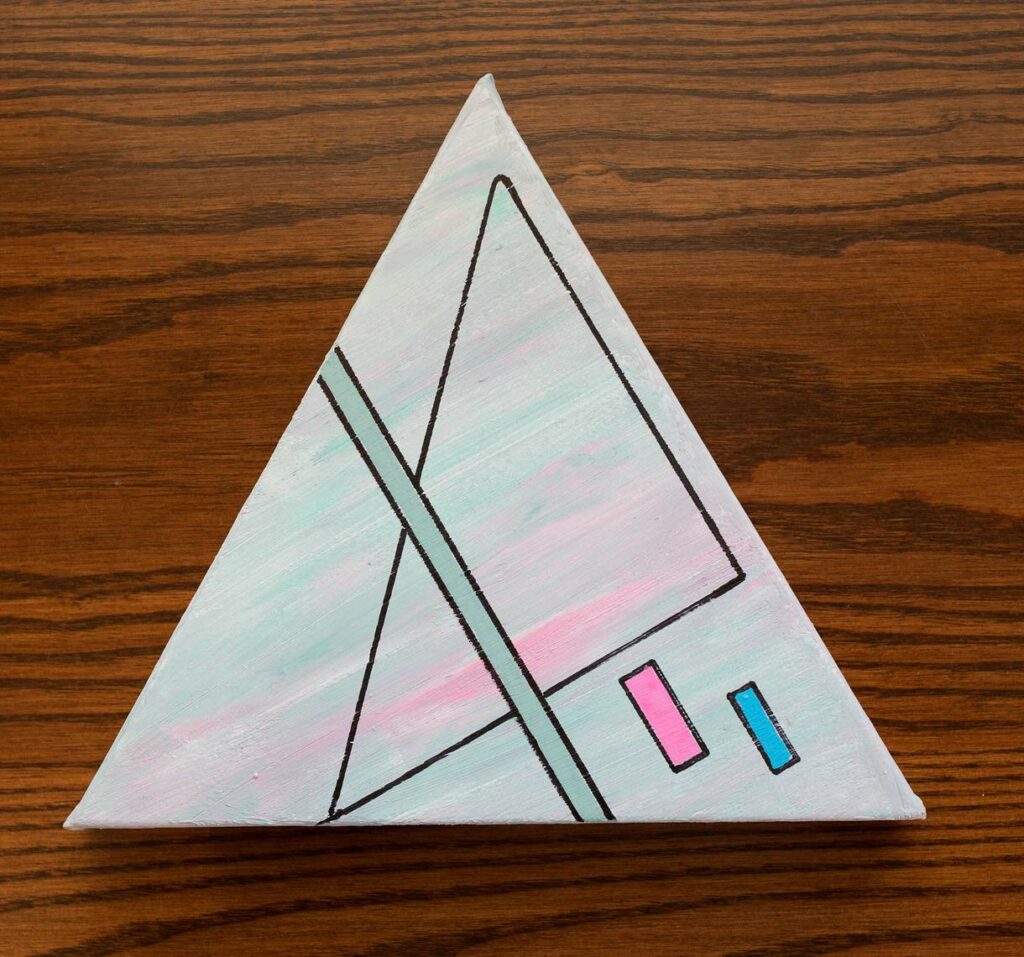

His subject matter, the triangle, has never been far from his reach.

“I started my own company in 1967. In those days the triangle was a tool of the trade,” he says. “You used it as an integral part of creating drawings. Because of its natural strength, it’s also an integral part of bridge building.”

Schoor’s interest in art was always pulling at him from just below the surface, even if he didn’t always recognize it.

“Periodically from the mid-80s until 2016, I would fool around and start to paint and try to find some relaxation and enjoyment in it,” he says. “A lot of it was predicated on what I used to say when I looked at abstract contemporary art in a museum or gallery. Looking at art that was selling for millions or tens of millions of dollars, I’d say to myself or my wife, ‘You know what? I can do that. ’”

“Periodically from the mid-80s until 2016, I would fool around and start to paint and try to find some relaxation and enjoyment in it,” he says. “A lot of it was predicated on what I used to say when I looked at abstract contemporary art in a museum or gallery. Looking at art that was selling for millions or tens of millions of dollars, I’d say to myself or my wife, ‘You know what? I can do that. ’”

In 2017, he recognized how much he enjoyed painting and started taking it seriously. “I showed my art to friends and relatives, and everybody sort of liked it,” Schoor says.

With the quickening pace of technology, the era of engineering that demanded manual drawing skills had come to a close. The time was right for a change of direction.

“What used to be a large room in my office with drafting tables and T-squares and triangles back in the late ’90s is now nothing more than cubicles with screens,” he says. “Everything is designed on a computer screen. It’s pretty difficult for someone of my age to adapt to that. Today every drawing looks alike.”

Self-taught with no formal art training except for the skills honed at drafting tables, Schoor uses acrylic paint, spackle paste, and markers to create interesting background colors. Always an avid art collector and observer, he believes that the most successful abstract artists have some signature element that makes them immediately recognizable.

For Schoor, it’s the triangle.

For Schoor, it’s the triangle.

“All of my art to date has a triangle in it — that’s the headline that I put on my artworks,” he says.

“In the fall of 2017, I confiscated several bays of the garage in my home in Jupiter, Florida, as my studio,” Schoor adds. “I essentially try to paint every day. It doesn’t feel like I’m going to work. It’s just a feeling that this is what I want to do.”

By any measure, he hasn’t let any grass grow under his triangles since undertaking his new pursuit.

Schoor completed a five-week artist residency last summer at Parlor Gallery in Asbury Park, N.J., which features original work by both breakout and established, internationally recognized artists.

On a visit to campus earlier this year to talk shop with Bob Mattison, Metzgar Professor of Art, and to visit his granddaughter, Kaitlyn Serpico ’22, he opened his leather-bound briefcase, which was stocked with samples of his artwork. After his stop at Lafayette, he headed east to meet with former businesses associates considering original artwork as part of the redevelopment of the former Bell Laboratories in Holmdel, N.J.

“I’m still going through this evolutionary process to determine what makes one artist successful and tens of thousands of artists not successful,” Schoor says. “It’s a work in progress—no conclusions yet.”

As an entrepreneur, businessman, and art collector, he has always been confounded by the pricing of art.

As an entrepreneur, businessman, and art collector, he has always been confounded by the pricing of art.

“It’s a contrived market, and it’s been that way since the beginning,” he says. “There’s no transparency in the art market. How do you justify an Andy Warhol Brillo Box originally selling for $1,000 and changing hands several times for less than $40,000 and ultimately selling at auction 30 years later at $30 million? It may take me 10 hours to create a piece of art with $75 worth of art supplies. But it doesn’t mean that the painting is worth $750 or $7,500 or $75,000—it’s just hard to find rationality in the pricing of art.”

Schoor has decided to sell his art on his website, howardschoorart.com, posting what the last similar piece of art sold for to give customers context of his pricing. He donates 25 percent of sales to one of a half-dozen of his favorite charities. If someone commissions a piece of art from him, he donates 25 percent to a charity of the commissioner’s choice.

Journey to Lafayette

“I was never one who could be classified as a good student. Through high school growing up on Staten Island I just wanted to get through, graduate, and make money,” Schoor says.

The first child in his immediate family to attend college, Schoor at first refused to take the college boards and went to work in New York City as draftsman apprentice, earning $125 a week.

“By the time I paid for food and travel costs, I was making $3.15 a week, and I decided that most of my friends went away to college and were having a good time and decided maybe I should go,” he recalls. “I started for a year at City College of New York, working half days and going to school at night. And I said “‘Literally this sucks.’”

He applied to Lafayette, Lehigh and Drexel universities, and Brooklyn Collegiate and Polytechnic Institute. He was accepted at Lafayette and Lehigh, choosing Lafayette because of its closer proximity to New York. He was a resident advisor at South College and McKeon Hall, and served meals at his fraternity to make extra money.

Advice for today’s students

“There’s a lot to be said for getting a well-rounded education,” Schoor says. “College was a learning experience for me. I told my kids and others that every day in life is a learning experience, and you should make the most of it.”

Back in the early 1970s, Schoor was invited to speak to a group of graduating civil engineering students. He was asked by a student where he graduated in the Class of 1961.

“I said I was number two. The student replied that she was number two in her class. I said ‘Yes, but I was number two from the bottom,’” Schoor laughs. “She wanted to crawl under the table.”

“I said I was number two. The student replied that she was number two in her class. I said ‘Yes, but I was number two from the bottom,’” Schoor laughs. “She wanted to crawl under the table.”

While he may not have been a stellar student, his instincts for business and entrepreneurship have served him well.

From 1967–92, he was CEO of Schoor DePalma Inc., an engineering and design firm based in Manalapan, N.J. In 1992, Schoor founded a residential home builder and land development firm, which he later sold to an NYSE-listed firm.

He then founded Community Bank of New Jersey (later sold to Sun Bancorp), established a land development and real estate consultancy, and formed a group of companies specializing in building custom country homes. In 2008, Schoor founded Seat Strap LLC in Boca Raton, Fla., for which he is CEO.

He formerly owned and operated Showplace Farms, a top Standardbred horse training facility in Millstone, N.J. He has chaired many fundraising campaigns including American Heart Association Heart Walks, Multiple Sclerosis, Centra State Medical Center, and Collier Youth Services Annual Gala. In 2003, along with his wife and children, he established Schoor Family Foundation.

In honor of Schoor’s support and service, Collier Youth Services, a nonprofit organization that supports at-risk and handicapped kids, established a humanitarian fund in his name.

Schoor provided significant funding for Schwartz-Schoor Plaza, bringing beauty to the area behind Lafayette’s Hogg Hall.

The discipline of civil engineering and his experiences at Lafayette have been welcome companions throughout Schoor’s life. He loved civil engineering from the start because of its sound logic.

“I was fascinated by construction of all sorts growing up,” he says, remembering how he would visit construction sites to pick up empty bottles to make a little pocket money.

“I always wanted to be an architect but never had the ability to translate what my brain saw to paper,” he says. “So civil engineering was the closest thing I could come up with to enjoy the construction and the forms and the creation of things. It’s likely what has led me to my new chapter as an artist.”

“Periodically from the mid-80s until 2016, I would fool around and start to paint and try to find some relaxation and enjoyment in it,” he says. “A lot of it was predicated on what I used to say when I looked at abstract contemporary art in a museum or gallery. Looking at art that was selling for millions or tens of millions of dollars, I’d say to myself or my wife, ‘You know what? I can do that. ’”

“Periodically from the mid-80s until 2016, I would fool around and start to paint and try to find some relaxation and enjoyment in it,” he says. “A lot of it was predicated on what I used to say when I looked at abstract contemporary art in a museum or gallery. Looking at art that was selling for millions or tens of millions of dollars, I’d say to myself or my wife, ‘You know what? I can do that. ’” For Schoor, it’s the triangle.

For Schoor, it’s the triangle. As an entrepreneur, businessman, and art collector, he has always been confounded by the pricing of art.

As an entrepreneur, businessman, and art collector, he has always been confounded by the pricing of art. “I said I was number two. The student replied that she was number two in her class. I said ‘Yes, but I was number two from the bottom,’” Schoor laughs. “She wanted to crawl under the table.”

“I said I was number two. The student replied that she was number two in her class. I said ‘Yes, but I was number two from the bottom,’” Schoor laughs. “She wanted to crawl under the table.”