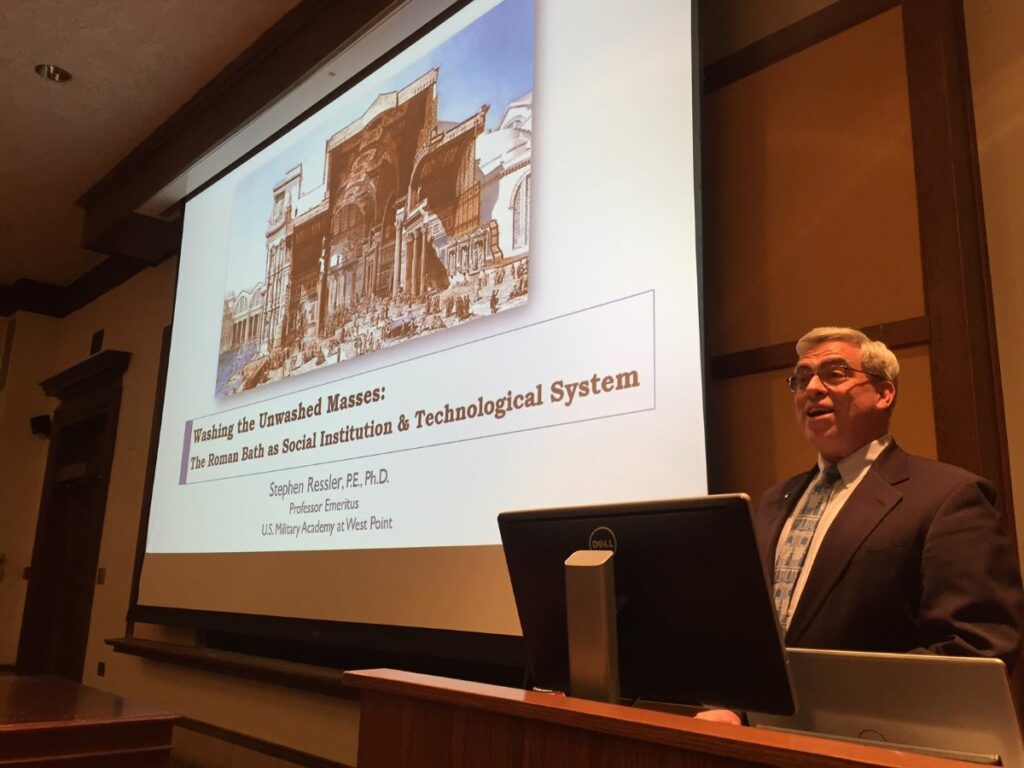

Marblestone lecturer Stephen Ressler brings to life Roman bath experience

By Bryan Hay

Before a packed auditorium in Kirby Hall of Civil Rights, Stephen Ressler, professor emeritus from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, delivered the 10th annual Howard J. Marblestone Memorial Lecture Oct. 24, bringing alive Roman ingenuity and culture as expressed in the empire’s complex public bath system.

More than covering the history and role of Roman baths, Ressler all but handed his rapt audience vials of oil, tunics, and towels as he took everyone with him for a dip into history and a topic that combined engineering and the humanities—very fitting for Lafayette.

Marvels of Roman engineering, public baths started early in Rome’s Republican era and spread into remote reaches of the provinces deep into the Imperial period. Even small towns far afield from Rome had Roman-style public bath complexes, from Scotland’s western lowlands to North Africa. Ressler said the baths started as early as the third century B.C., in the Greek colonies of southern Italy, as a way to promote public health. During the Imperial era, emperors used them to project their undisputed power over fire and water and benevolence, providing unskilled jobs for the urban poor.

“It’s a very powerful reflection of Roman culture, a product of the Roman love of all things Greek,” Ressler said.

For Romans living in cramped apartments, the baths, with facilities for both men and women, provided a crucial community center to escape the confines of city living. By the first century, baths were exploding in popularity on the Italian peninsula. The Eternal City provided more than 800 bath facilities during that era.

Noting that the only way to understand the rituals involved in Roman public bathing is to experience it, Ressler brought everyone into the Stabian Baths in Pompeii, built around 140 B.C. when the Roman bath experience was just taking off. Ruins are still largely intact, having survived the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D.

Oil and water

It’s noon, another workday over, and time for up-and-coming patricians living in Pompeii to head to the Stabian Baths, the oldest public bath facility in the wealthy, ancient city, to get greasy, sweaty, and wet.

A Pompeiian arriving with ritzy towels, robes, and servants to express social status might browse the shops selling food and drink, an integral part of the bathing experience, beneath the vaulted structures and open plaza on the south and west sides of the facility.

“Bathing was more than bathing for hygiene purposes,” Ressler said. “It was a social endeavor, and eating and drinking were part of that.”

After dropping off your belongings in the vestibule, you enter the apodyterium (Greek for “undressing room”) to change and prep for bathing. Once divested of your clothing, you’re rubbed down with oil, likely olive oil. “There was no soap in the ancient world, and this was the equivalent of soap,” Ressler noted.

Covered in oil, you head to the open courtyard, the palestra, to do some exercising and perhaps take a dip in an open-air pool to cool off after your workout.

Sweat

After exercising for about an hour, your body covered with oil, sweat, and dirt, it’s time to start the ritualistic bathing process, starting in the tepidarium (Latin for “lukewarm room”), a room with heated floors but not as hot as the next room, the caldarium (Latin for “hot room”), located near the furnace. Wooden flip-flops, as depicted in a mural from the period, were required to prevent the soles of the feet from burning. Cold-water basins allowed bathers to splash water on their faces to survive in this environment, Ressler said.

“Roman bathing was founded on the principle that sweating is good for you,” Ressler said.

The Strigil

To prepare for the final stages of bath time, you reach into your personal bath kit for a strigil, a curved metal tool used to meticulously scrape the oil, dirt, and sweat from your body. If you were a person of means, a slave or attendant would perform this task, Ressler said, adding that the pasty mess would simply be flipped onto the stucco walls.

Frigidarium

You now work your way into the frigidarium (Latin for “cold room”), a room with a large circular stone cold-water pool for swimming. Body temperature lowered, you’re surrounded by exquisite decorations and statuary depicting mythological scenes, with snacks and drinks nearby.

Nature Calls

After three to four hours in the bathhouse, it’s pretty likely that nature will call, Ressler said. A latrine on the north side of the facility provided an open wooden seating area with two water channels running underneath to flush waste. A public swab, antiquity’s Charmin, was used by everyone.

“Remember, Roman baths are all about hygiene,” Ressler said with a grin. “Roman bathhouses contributed to a sense of community. You can’t sit in a public toilet without having a sense of community.”

Finis

Finis

“The Roman public baths grew to become an integral part of what it meant to be a Roman throughout the provinces and the empire,” Ressler said. “It started out for public health but ultimately transformed into a leisure experience and a reflection of the power of Roman civilization, enabled by masterful engineering prowess. There’s a lot more to Roman baths than just washing the unwashed masses.”

Ressler left his audience with the popular Latin slogan from ancient Rome: “salvom lavisse,” bathing is good for you.

About the speaker

Stephen Ressler is professor emeritus from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y. Prior to his retirement from full-time teaching in 2013, he served as professor and head of the Department of Civil and Mechanical Engineering. He holds a B.S. degree from the U.S. Military Academy, and M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in civil engineering from Lehigh University, and a master of strategic studies degree from the U.S. Army War College.

Ressler served for 34 years as a commissioned officer in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and retired at the rank of brigadier general. A sought-after presenter who has received many professional awards throughout his career, he recently received the 2019 President’s Award of the American Society of Civil Engineers.

His service included a variety of military engineering assignments in the U.S., Europe, and Central Asia, including service as Deputy Commander of the New York District, Corps of Engineers.

About the annual Howard J. Marblestone Memorial Lecture

The lecture series was established in memory of Howard Marblestone, Charles Elliott Professor of Foreign Languages and Literatures. A member of the faculty for more than 30 years, he taught courses in Greek, Latin, biblical Hebrew, and modern Hebrew languages and literatures; classical literature in translation; classical mythology; and the ancient history of Greece, Rome, and Israel. He was the coordinator of the interdisciplinary classical civilizations minor.

Finis

Finis