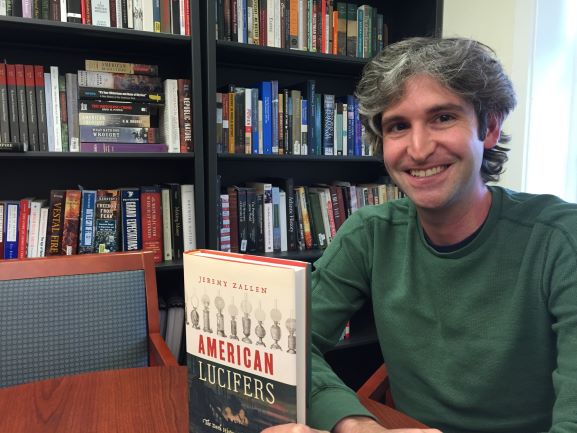

Prof. Jeremy Zallen explores production and consumption of artificial light before the incandescent bulb in his new book, American Lucifers: The Dark History of Artificial Light, 1750-1865

By Bryan Hay

Artificial light may have liberated humanity and led to more hours of leisure time free from the cycles of the sun and moon. But the production of whale oil, gas, and kerosene that fueled illumination before the incandescent bulb exploited children and women laborers, instituted industrial slavery, and caused environmental damage that still lingers today in the pursuit of cheap ways to create light.

Jeremy Zallen, assistant professor of history, explores the rarely talked about stories behind the human costs of creating artificial light from 1750 to the end of the Civil War in his first book, American Lucifers: The Dark History of Artificial Light, 1750-1865, published by University of North Carolina Press.

From consumption of whale oil in the 18th century to kerosene and the roasting of coal to make coal gas in the 19th century, Zallen’s six chapters reveal how people struggled and risked their lives to provide light for an expanding economy. While some profited by artificial light, it brought about a less charitable outcome for others, particularly the working poor, who could now toil into the wee hours of the night to increase their production in support of industrial capitalism.

The book describes how “the myth of light and progress has blinded us. In our electric world, we are everywhere surrounded by effortlessly glowing lights that simply exist, as they should, seeming clear and comforting proof that human genius means the present will always be better than the past, and the future better still. At best, this is half the story. At worst, it is a lie.”

What inspired you to write this book?

I’ve been interested in exploring something from the history of energy or environmental history, a topic that would help me talk about production and consumption of energy. Light is part of that. Reading Moby Dick solidified it for me and helped me understand the work that goes into light and how dangerous that is. I felt that this story needed to be told.

Where did your research lead you?

It started in grad school at Harvard; the first piece was about the Boston Bijou Theatre, the first electrically lit theater in the United States, powered by one of Edison’s isolated electrical systems. From there I became interested in copper mining—electricity needs copper at scale—and traveled to Butte, Montana, where I studied coroner reports from the late 1800s and read about people dying of silicosis. Then I started looking at whaling journals at Harvard, New Bedford, and Nantucket, and traveled to Duke to sift through the business records of enslavers in North Carolina who ran turpentine operations.

What are some of the illuminants that most surprised you during your research?

The most surprising chapter was about a mix of turpentine and highly distilled alcohol, a volatile material called camphene that was used widely by the poor and middle class to illuminate homes from the 1840s to 1861. It replaced whale oil. It also blew up all the time. It was cheap, and if you spilled it on furniture, no stain was left behind, but it would easily detonate like napalm. I described in the book how the handling of camphene was one of the deadliest activities of the antebellum period.

One of the things that sticks with me the most, in a haunting sense because I was shocked not to have known about it, were the thousands of children who glowed in the dark because of their work dipping matches. They got covered in phosphorous from the dust and fumes that got into their clothes. It got in their skin and saliva and some developed a condition called phossy jaw, where certain cells in the jawbone started to grow abnormally. The only thing that would help would be the removal of all or part of the jaw. Disfigured and glowing, they felt like no one wanted to be around them; it seemed like something out of a Dickens novel.

What are some lessons from the book that can be applied today?

We have a basic faith that technology is a force for good. Part of what I want people to do is look at the actual history of lighting and realize that, even though it turned out OK eventually, there was no reason that it had to lead to more suffering for many people. Reflect on your own work and think harder about all of the things that we use in life that we don’t think about. How many touched it, where did it come from?

The system is designed so that we can’t really know where everyday products are from. Hopefully, more people will demand that kind of information.