Kryptos artist Jim Sanborn discusses his work and current exhibition Looted?

By Stephen Wilson

Outside the headquarters of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (in Silver Spring, Md.), workers and visitors can sip coffee and sit for a moment beneath the trees near a fountain that roars with waves.

The wave pool might serve as a momentary backdrop, perfect for a selfie or a loud and rhythmic break from a busy mind.

What most people don’t know is that the waves are an exact re-creation of a 65-foot section of the Atlantic coast. A sensor in the town of Woods Hole, Mass., transmits tide data to a turbine under the sculpture to generate real-time artificial waves.

What most people don’t know is that the waves are an exact re-creation of a 65-foot section of the Atlantic coast. A sensor in the town of Woods Hole, Mass., transmits tide data to a turbine under the sculpture to generate real-time artificial waves.

Artist Jim Sanborn created Coastline as he does much of his work—precisely hiding the real inside the ordinary which then, upon discovery, makes the ordinary feel extraordinary.

Case in point, he built a working particle accelerator that splits uranium atoms. Or take his exact replica, with both acquired original items and constructed pieces, of the Los Alamos lab used for the Manhattan Project.

Maybe this penchant for historical re-creation began as a boy—he recalls sitting in his father’s office at the Library of Congress where the Dead Sea Scrolls were spread across the desk and seeing his father handcuffed to a briefcase carrying an original Gutenberg Bible. Such artifacts were “a readily available resource to me as a kid.”

From a boy who wanted to be an archeologist, Sanborn now mines history, science, and math to create notable artistic works.

Kryptos

“Between subtle shading and the absence of light lies the nuance of iqlusion.” That sentence is the translation of the first panel of coded text on Sanborn’s sculpture Kryptos, which graces the central courtyard of Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) headquarters.

Notice the q in the word illusion. It’s intentional. Why? The world is not yet certain. Only three of the four panels are solved despite their being installed in 1989.

Latin for “hidden,” Kryptos was commissioned in 1987. Sanborn worked with Ed Scheidt, chairman of CIA’s Cryptographic Center, to learn to encrypt his text. The code gets progressively more difficult as people pass the work and approach the main doors.

The copper panels were hand-cut, which took two years, nine jigsaws, and 900 blades.

Sanborn gave part of the code’s translation to William Webster, then director of the CIA.

California computer scientist Jim Gillogly was the first person to publicly announce he had solved the first three panels in 1999. Not to be outdone, the CIA quickly announced that David Stein, a CIA analyst, had solved the first three panels in 1998. Then in a seeming game of one upmanship, the National Security Agency said a team solved those panels in 1992.

Sanborn has been in the news recently when he released his third and final clue for the fourth panel. “Northeast” was the word he provided. It was preceded in 2010 with the cipher text NYPVTT decrypted to “Berlin” and in 2014 with the word “Clock” immediately following the word “Berlin.”

Sanborn made clear if the fourth panel is decrypted a fifth puzzle will emerge from the four panels. The payoff? “Some unplanned activity for the agency,” he says.

If Sanborn dies before Kryptos is solved, he indicates the piece will be sold at auction with proceeds to benefit climate science research.

While working with the CIA, Sanborn negotiated a deal where he could take buckets of paper pulp, the preferred method for classified document destruction after shredding proved to be less than reliable, in exchange for the completed text from Kryptos.

While Sanborn gathered pulp, he didn’t keep his end of the bargain. He did, however, construct relief sculptures that resemble cuneiform tablets using encoded English and Arabic text from covert operations carried out in Iraq and Central Asia.

A few of those pieces, Babylon III and Babylon VI, cut from a room-size installation, are on display in Williams Center Gallery as part of his Looted? exhibition.

Looted?

The question mark is the key to the exhibit title.

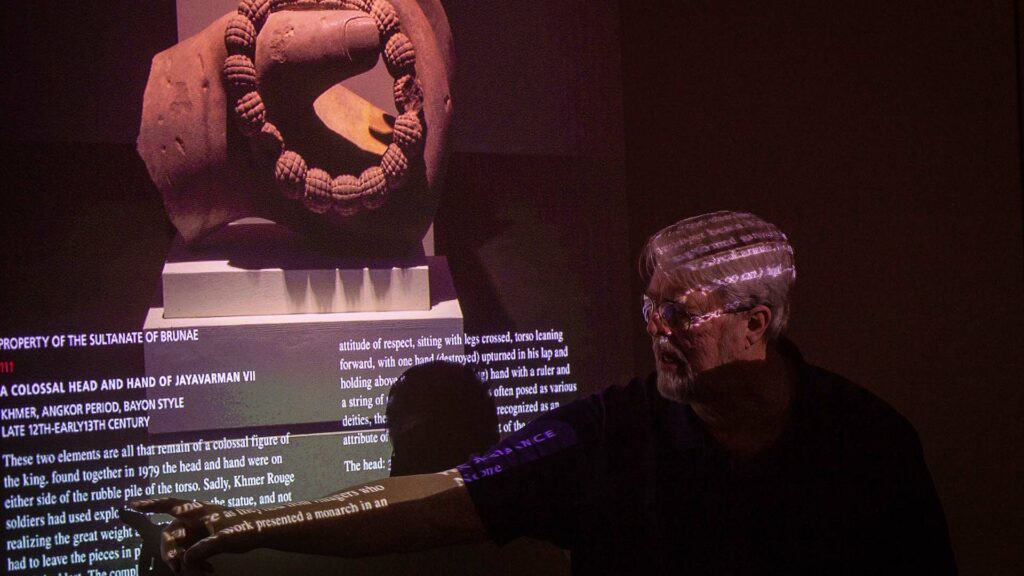

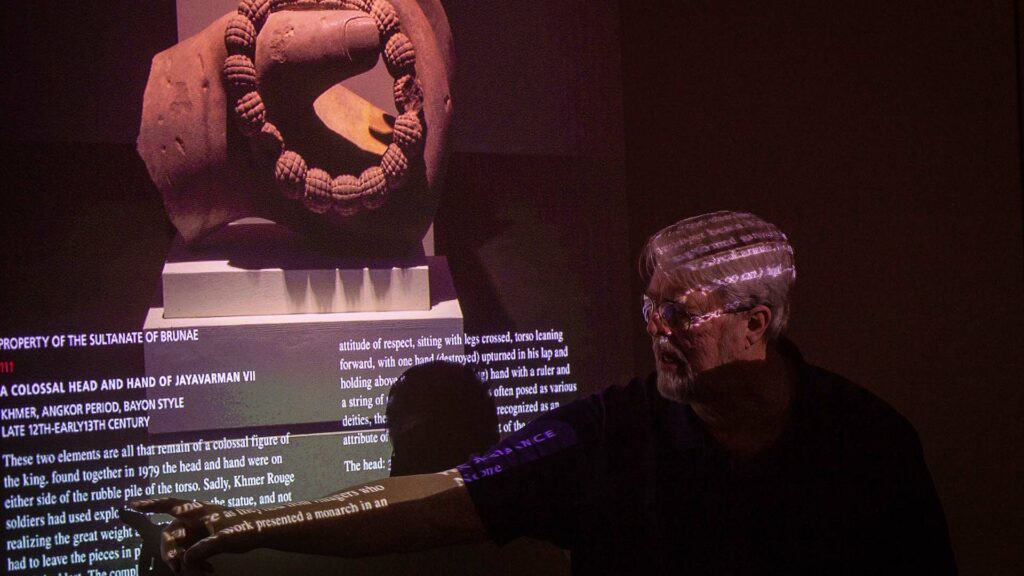

The Khmer sculptures displayed in the gallery are in an auction house-like setting. Despite looking like antiquities, the stone sculptures were made within the past decade.

Sanborn has created what he calls “high-end reproductions.” As stated on a gallery exhibition label: “The works in this installation are not museum shop ‘replicas’ because they are not cheaply mass-produced. They are not ‘forgeries’ either because this implies that the pieces are offered for sale as genuine antiquities, which they are not. These pieces can, however, be called ‘high-end reproductions’ or ‘contemporary antiquities.’”

Sanborn has created what he calls “high-end reproductions.” As stated on a gallery exhibition label: “The works in this installation are not museum shop ‘replicas’ because they are not cheaply mass-produced. They are not ‘forgeries’ either because this implies that the pieces are offered for sale as genuine antiquities, which they are not. These pieces can, however, be called ‘high-end reproductions’ or ‘contemporary antiquities.’”

To create the work, Sanborn traveled to Cambodia, visited Khmer sites, met with noted forgers, spoke with government workers who alter authenticity documents, and snuck into a looter’s compound. He discovered the processes used to make reproductions that are indistinguishable from originals to noted curators.

Then he set to work, commissioning reproductions from local forgers and using his own techniques to color, date, and weather the pieces.

Auction catalog pages that accompany each “antiquity” both accurately describe the work and, using ironic fiction, describe how looted pieces make it to the auction house.

As for that question mark in the exhibit title, nearly 70% of Khmer antiquities in public and private collections are either looted or fake.

As for that question mark in the exhibit title, nearly 70% of Khmer antiquities in public and private collections are either looted or fake.

Looking at Sanborn’s work leads to questions: Is looting necessary anymore? Could high-end reproductions slow the destruction of cultural sites? Could buyers become more aware of the impact of looting or forgery practices? Could curators prevent themselves from being duped?

For Sanborn, it seems the answers often are hiding in plain sight.

What most people don’t know is that the waves are an exact re-creation of a 65-foot section of the Atlantic coast. A sensor in the town of Woods Hole, Mass., transmits tide data to a turbine under the sculpture to generate real-time artificial waves.

What most people don’t know is that the waves are an exact re-creation of a 65-foot section of the Atlantic coast. A sensor in the town of Woods Hole, Mass., transmits tide data to a turbine under the sculpture to generate real-time artificial waves.

Sanborn has created what he calls “high-end reproductions.” As stated on a gallery exhibition label: “The works in this installation are not museum shop ‘replicas’ because they are not cheaply mass-produced. They are not ‘forgeries’ either because this implies that the pieces are offered for sale as genuine antiquities, which they are not. These pieces can, however, be called ‘high-end reproductions’ or ‘contemporary antiquities.’”

Sanborn has created what he calls “high-end reproductions.” As stated on a gallery exhibition label: “The works in this installation are not museum shop ‘replicas’ because they are not cheaply mass-produced. They are not ‘forgeries’ either because this implies that the pieces are offered for sale as genuine antiquities, which they are not. These pieces can, however, be called ‘high-end reproductions’ or ‘contemporary antiquities.’” As for that question mark in the exhibit title, nearly 70% of Khmer antiquities in public and private collections are either looted or fake.

As for that question mark in the exhibit title, nearly 70% of Khmer antiquities in public and private collections are either looted or fake.