Jim Toia visits Joshua Tree, California, to advance his ‘Desert Crust Preservation Project’ art soil project

By Stephen Wilson

A pack of four-wheelers move across some well-worn ruts on an off-road trail while a group of scouts, gathered at a trailhead map, start to wind along a footpath. Two cars pull in weighted down by bike racks, and couples step out in gear ready for a ride. Seems a typical day of education and recreation at any state park across the country.

In the desert southwest, such a day could be a recipe for disaster.

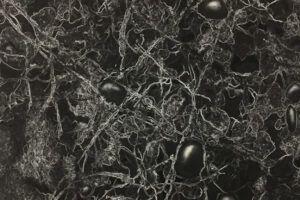

Not unintentional accidents that can occur during outdoor activities, but destruction of the cryptobiotic soil that forms the desert crust. A woven mat made up of layers of living organisms, like lichen, moss, bacteria, algae, and mycelium, cryptobiotic soil helps prevent erosion, retains water and nutrients, serves as habitat for desert life, and absorbs a large volume of carbon dioxide.

Footprints and tire treads easily break and bury the crust, allowing those spots to turn into sand dunes. The crust can take years to regenerate and decades to recover.

Most park visitors are unaware of how a misplaced footstep or an off-road jaunt can forever change the landscape.

Most park visitors are unaware of how a misplaced footstep or an off-road jaunt can forever change the landscape.

This is where Jim Toia enters the picture. Director of community-based teaching at Lafayette and chair of the Karl Stirner Arts Trail, Toia has been working for several years on an artist residency at BoxoPROJECT in Joshua Tree, Calif., to develop art that could help educate the public about cryptobiotic soils.

“It began with an invitation from Boxo’s director Bernard Leibov and research generously funded by the College, which allowed me to visit over long weekends and talk with biologists and environmentalists to better understand the vulnerabilities of the environment and the different threats to the ecosystem,” says Toia.

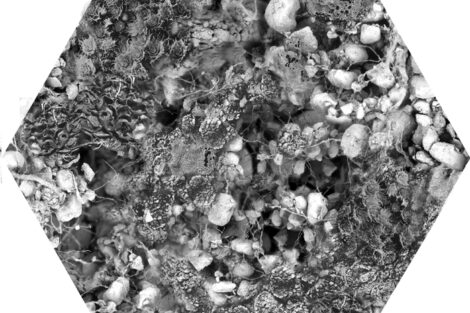

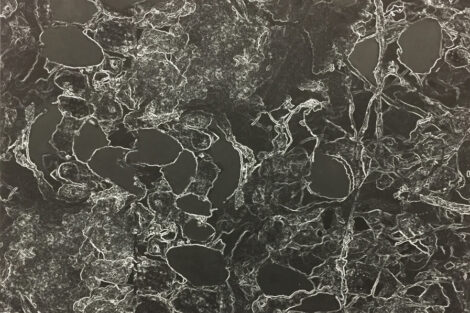

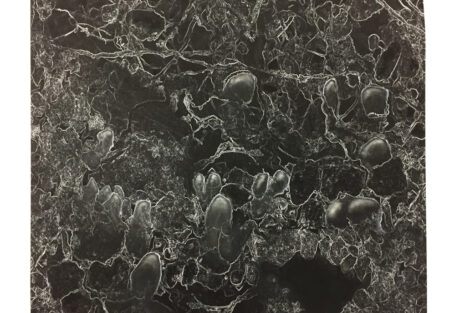

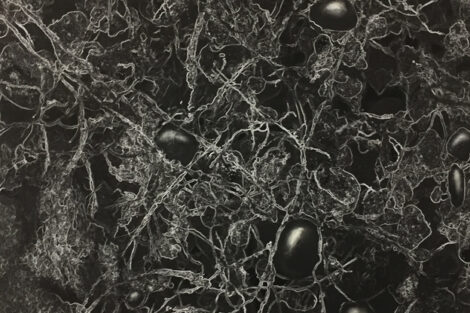

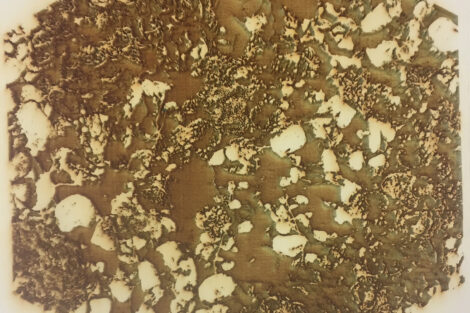

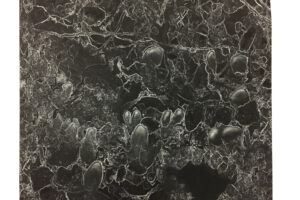

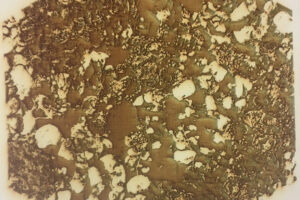

Of all the aspects of nature, he kept returning to the soil. He brought a small sample back to the College and used an electron microscope to take images of the layers.

He had assistance with this stage from Jane Ferguson ’21, a summer EXCEL Scholar and math and art double major.

Her interest in fractal geometry intersected well with the soil that exhibits what she calls “fractal behavior.”

She worked to isolate layers within the cryptobiotic structure and to replicate it faithfull(y) in Photoshop.

“This project combined everything I am excited about rather than keep my mind partitioned as a naturalist, artist, and mathematician,” she says.

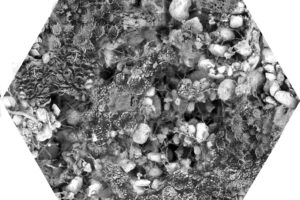

Those images served as the base compositions for what developed next between Toia and award-winning architect and professor Joe Biondo.

Toia began to burn the images into high-density foam to form hexagonal molds.

“The hexagon form is a prevalent form in nature, science, and engineering, appearing in the snowflakes, beehives, bolt heads, and insect eyes,” says Biondo.

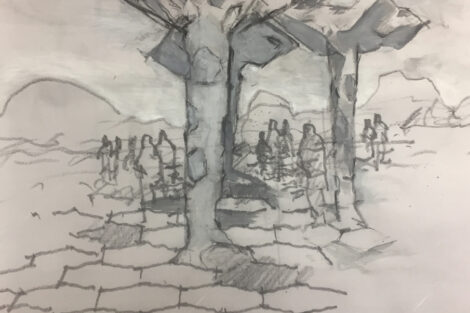

Toia and Biondo worked on the goal of transforming Toia’s artistic hexagons into structures that could serve as educational tablets at trailheads, kiosks, or even visitor centers.

“When artistic aspects cross boundaries with technical aspects, magic happens,” says Biondo. “Hexagons have an organic feel and can easily make structures like floors, columns, and canopies.”

Biondo began sketching various looks for what could be developed—a series of structures from modest to ambitious.

With artistic images and architectural sketches, Toia then went back out to the desert, spending several weeks at BoxoPROJECT. He had a studio at his disposal and thousands of acres of the natural world to explore.

“The space is so isolated,” he says. “I had a lot of time in the studio and to venture out.”

His first few days there brought fog and rain. Thanks to the cryptobiotic soil, the moisture fed the landscape with flora and fauna bursting to life.

In this visual feast, his hikes in 49 Palms Oasis and Black Rock Panoramic Loop helped his art evolve.

“The hikes helped inform new approaches as I manipulated the printed images,” he says.

He also met with several parks, institutes, and land trusts to discuss how to bring protection of cryptobiotic soil to life through education, art, and architecture.

“The generosity of all who have a deep and abiding love of the Mojave Desert landscape has enriched this experience beyond my hopes.” says Toia. “Then to bring this idea home and be received with such enthusiasm by my many collaborators is what has made this project so successful.”

Most park visitors are unaware of how a misplaced footstep or an off-road jaunt can forever change the landscape.

Most park visitors are unaware of how a misplaced footstep or an off-road jaunt can forever change the landscape.