With the help of at-home neuroscience lab kits, students studying remotely are successfully learning about brain architecture and function

By Shannon Sigafoos

Wearing a lab coat and using surgical tools, Luis Schettino, associate professor of psychology and neuroscience, stands in front of a camera in his classroom and walks his students through cutting into a sheep’s brain.

The end goal of the psychology department and neuroscience program’s Physiological Psychology 2 lab (designed by Schettino and assistant professor of psychology and neuroscience, Michelle Tomaszycki) is not just about providing an at-home look at how the mammalian brain is organized. The object is to impress on students the importance of brain architecture on the control of behavior—in particular, how complex behavior is controlled during human interactions.

Schettino is also connecting the exercise to one of today’s most relevant topics: the use of force by police officers when arresting minority individuals.

Prof. Luis Schettino leads his Physiological Psychology 2 lab in the dissection of a sheep’s brain.

“It exemplifies the way our brains work. As products of biological evolution, our brains have more than one channel for memory formation and for behavioral output. One of those channels is more emotional, faster, and automatic; another channel is more deliberate, slower, and effortful,” says Schettino. “During an arrest, when emotions run high, both the police officer and the suspect are more likely to use the first, more emotional channel and be guided by biased memories. Last year, one of my thesis students investigated how minority individuals respond to images of police officers. The basic question was whether images of police officers increase the possibility of a fight or flight response. Unfortunately, due to the pandemic we were not able to run a full sample.”

Why use a sheep’s brain? Its structures are in roughly the same place as those of the human brain, which makes it easier to discuss how each part functions. For the neuroanatomy module, students taking the course remotely received kits ( containing the brain (preserved without the use of toxic chemicals), gloves, bench paper, and modeling clay.

Prof. Luis Schettino works with the kit that was sent to students to complete the dissection of a sheep’s brain at home.

The clay was used during the first lab session to create “brain models” meant to give students a feel for the 3D organization of the brain. The next two sessions involve the sheep brain dissection. Students follow Schettino’s explanation as he shows the brain to the camera and guides them through top, bottom, and lateral views. Then they cut the brain in two and do the same looking at each structure. The cuts explore the internal layout of the brain, always considering the evolutionary history of the structures.

Lab kits put together by the department also provide the same rigor, relevance, and results as traditional labs, giving students who are distance-learning a successful experience with the module. The second module of the course will involve rats in a maze. Half the rats will undergo brain lesions of the hippocampus, and the other half will be sham controls. Schettino will record the rats learning to solve the maze for a week, then upload the videos for the students to code.

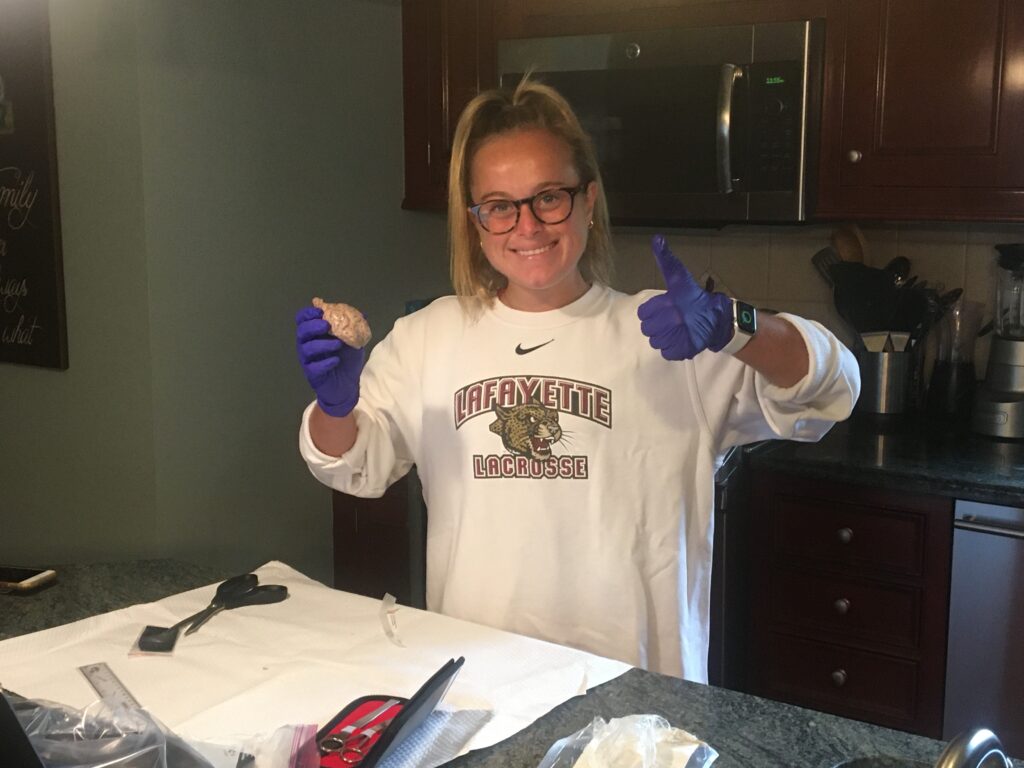

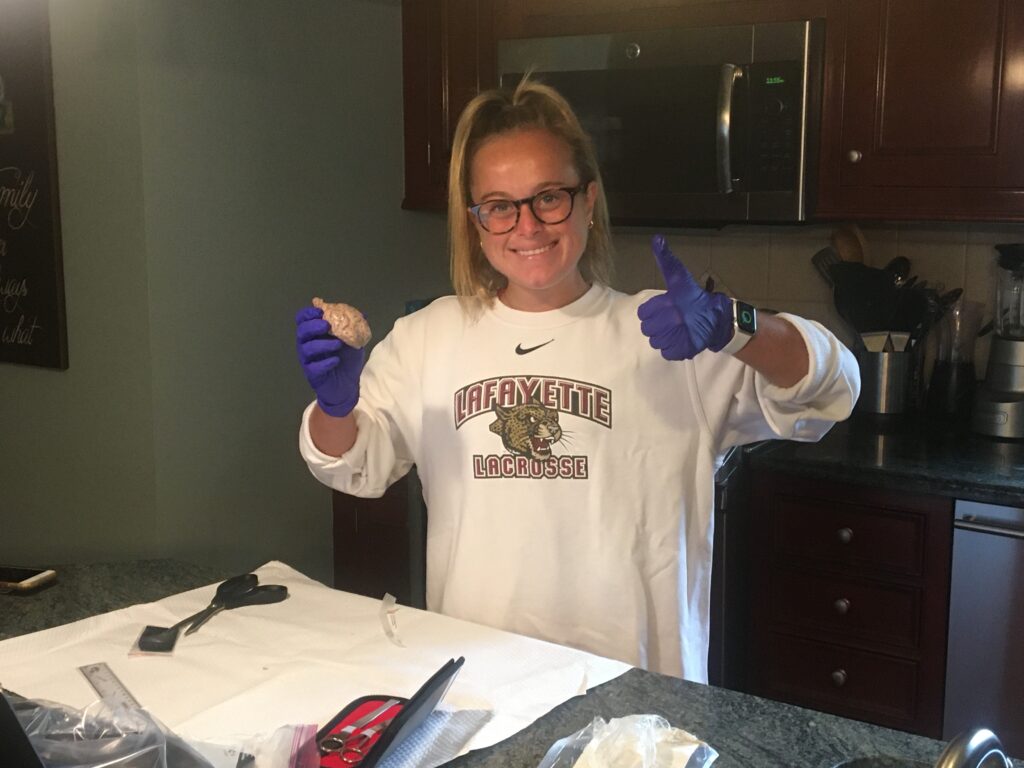

Maggie Ledwith ’22 shared this photo of herself working on the sheep brain dissection with the Lafayette social media community.

“This course is extremely engaging. Professor Schettino designed the course to ensure our continued interest, and we’ve discussed the parts of the brain in relation to the way our brains develop and how it affects perception, emotion, cognition, and behavior,” says Maggie Ledwith ’22. “We’re using this information to draw conclusions on why people act violently, commit crimes, and how our environment may lead to biases like racism. Performing a dissection on a sheep’s brain at home was not something I would have foreseen myself doing, but the psychology department and neuroscience program did a great job preparing us for the procedure and ensuring we had the resources to carry out the lab.”

For a small organ, the sheep’s brain is teaching students in the course a much bigger lesson.

“By learning the role that brain architecture plays on how humans behave, we become aware of our weaknesses and of the need to find solutions that take into account those limitations,” says Schettino. “Fomenting environments and skills that help keep in check our emotional channels and impulsivity could be a good avenue for preventing the expression of our biases.”

Several media outlets have covered this story. Read more:

Futurism’s coverage.

The Nerdist’s coverage.

The Daily Mail’s coverage.

1 Comment

The company referenced on Prof. Schettino’s lab coat is VICTOR NEUROTECH, an imaginary brain products company owned by Victor Frankenstein, the lead fictional character in FRANKENSTEIN2029 a multi-venue, mixed media performance staged on the Arts Campus in 2015. Schettino demonstrated his acting skills as a lead scientist working for the company. The performance was made possible by the hard work of 26 faculty and over 120 students. It drew 1200 attendees over three performances. Schettino is one of our great faculty members who sees the value of collaboration between science and art. check out the sites below.

http://www.victorneurotech.com

https://sites.lafayette.edu/frankenstein2029/

Comments are closed.